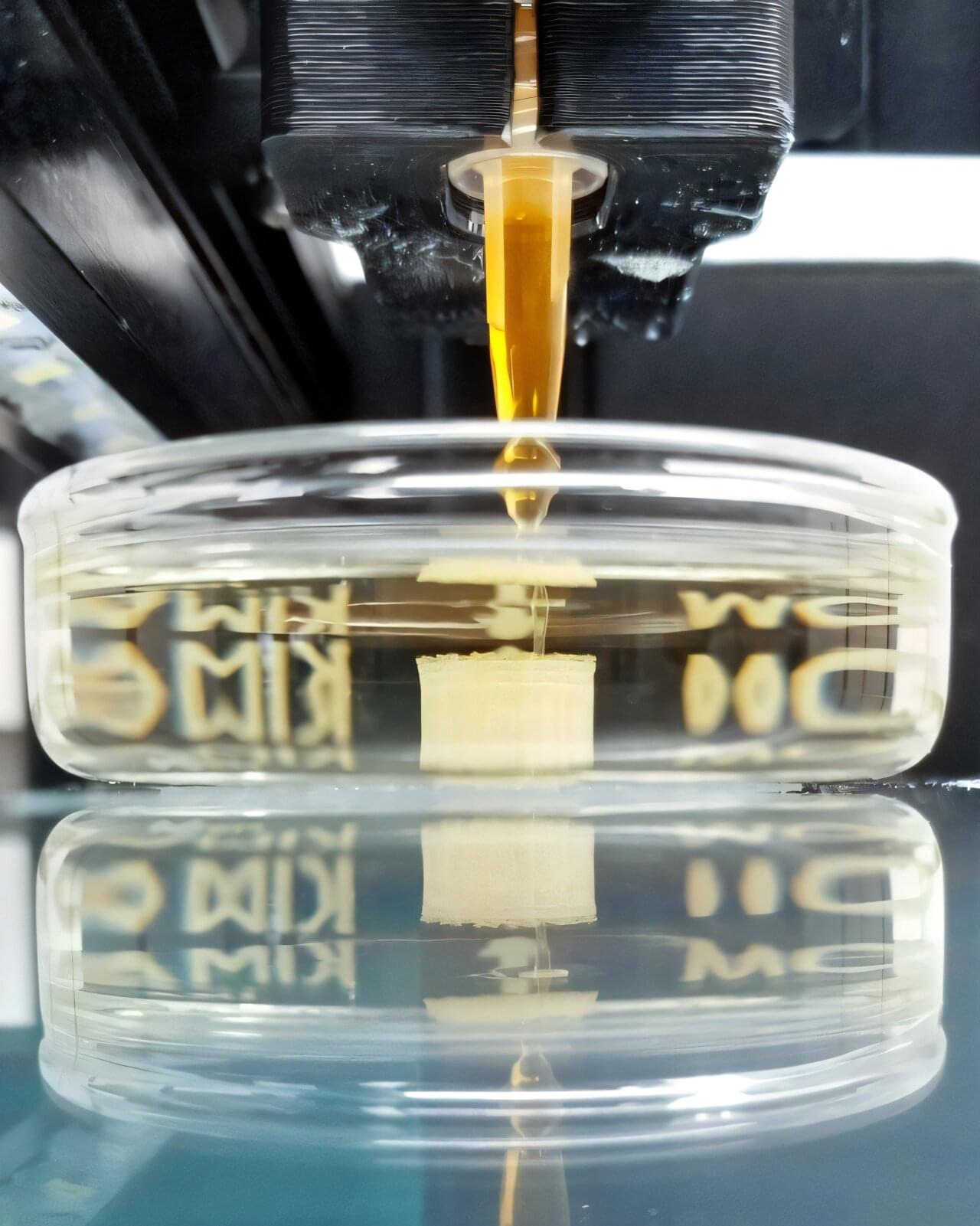

Nearly a decade after they first demonstrated that soft materials could guide the formation of superconductors, Cornell researchers have achieved a one-step, 3D printing method that produces superconductors with record properties.

The advance, detailed in Nature Communications, builds on years of interdisciplinary work led by Ulrich Wiesner, the Spencer T. Olin Professor in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering, and could improve technologies such as superconducting magnets and quantum devices.

Wiesner and colleagues reported in 2016 the first self-assembled superconductor using block copolymers—soft, chain-like molecules that naturally arrange themselves into orderly, repeating nanoscale structures. By 2021, the group found that these soft material approaches could produce superconducting properties on par with conventional methods.