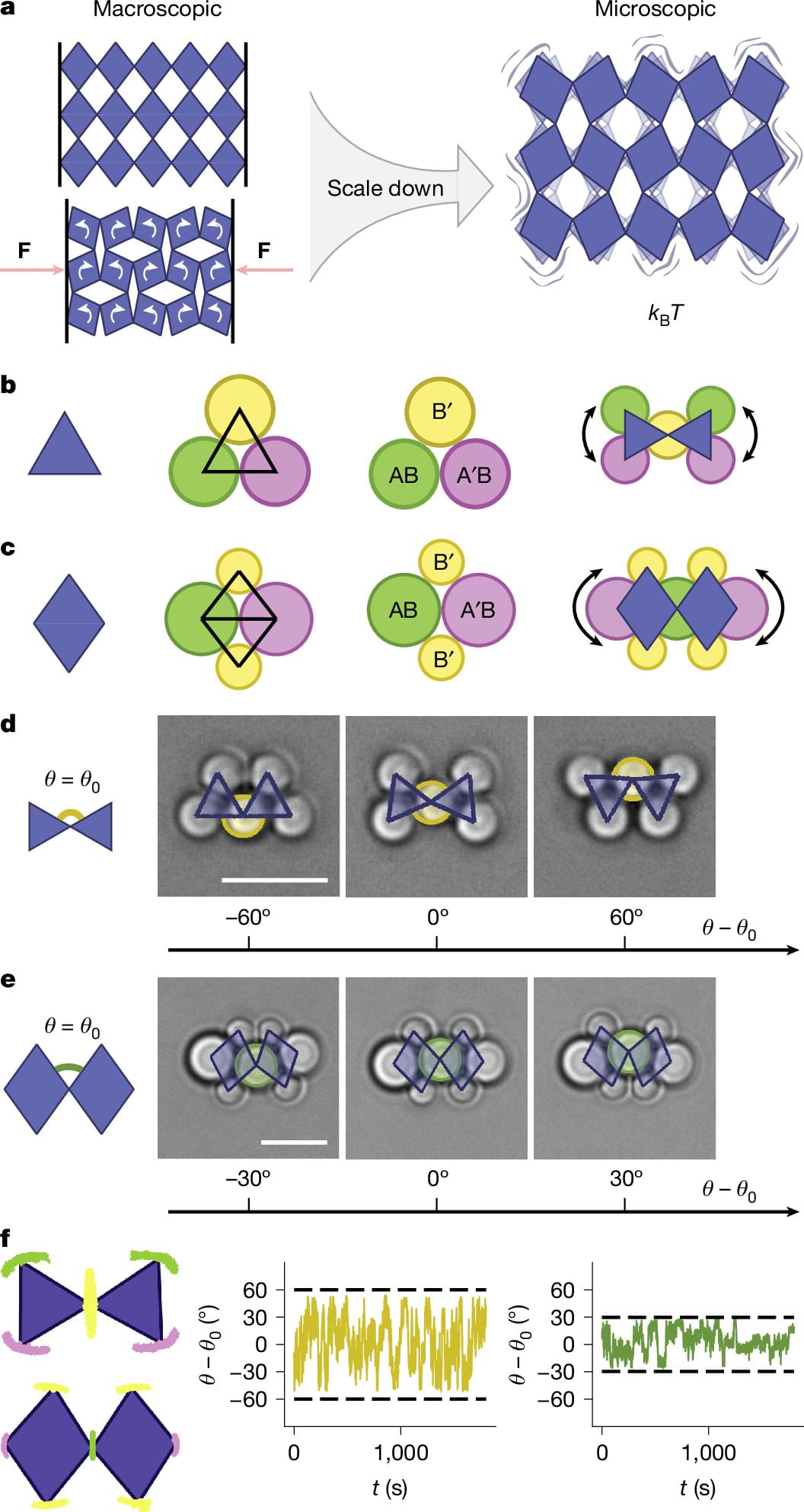

By organizing these pivots into geometric patterns—specifically triangles (Kagome) and diamonds—the team created “Brownian metamaterials.” These aren’t just static objects; they are structures with targeted deformation modes.

Editor’s note: raised a $100m Series A in September and is rumored to have reached a unicorn valuation. They have all-star advisors from Geoff Hinton to Yann Lecun and team of deep domain experts to tackle this next frontier in AI applications.

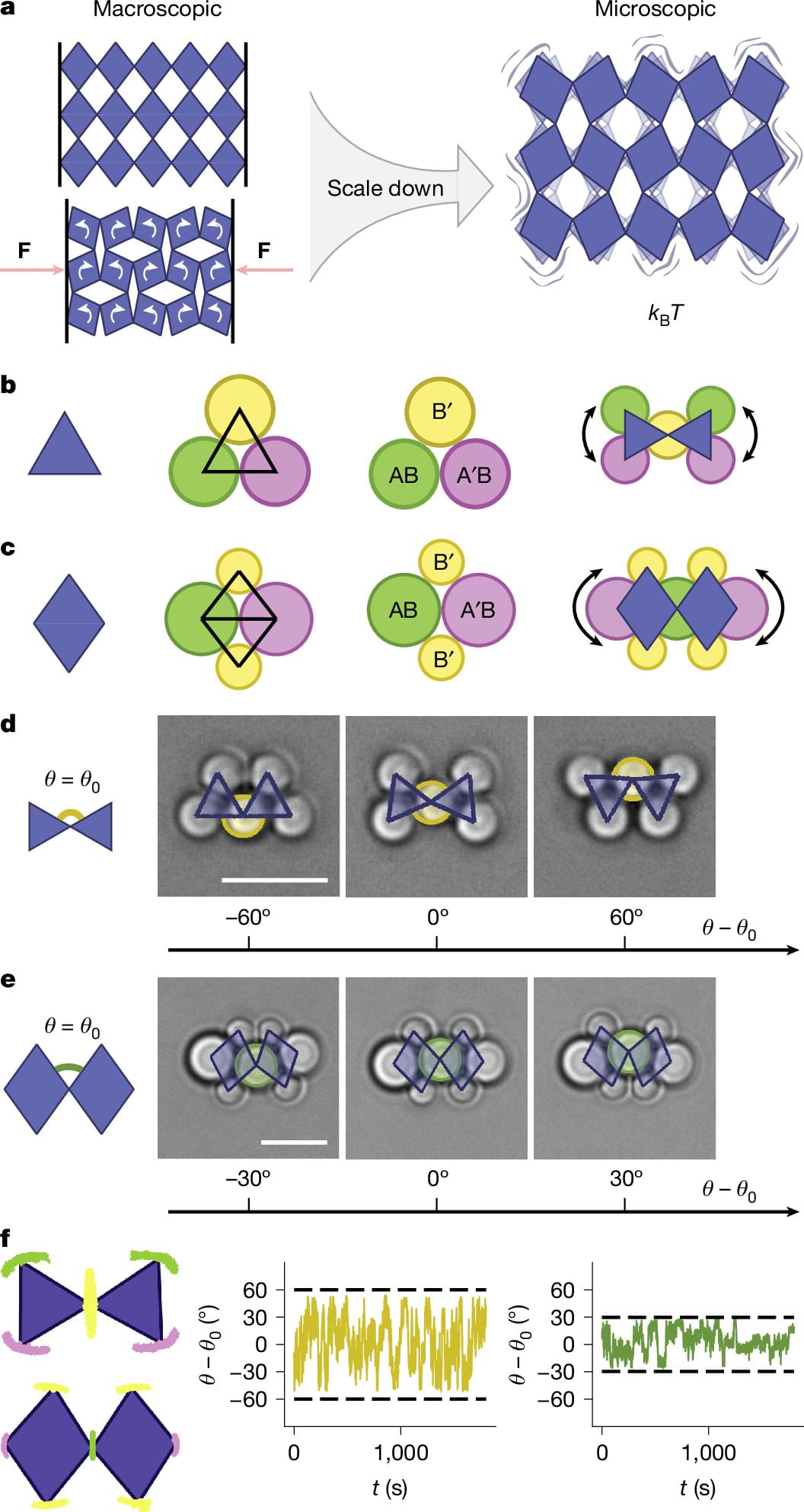

New generations of memristors could reliably store information directly within the molecular structures of graphene-like materials. In a new review published in Nanoenergy Advances, Gennady Panin of the Russian Academy of Sciences shows how these atomically thin materials are ideally suited for electrical circuits that mimic the function of our own brains—and could help address the vast power requirements of emerging AI technologies.

A memristor is a cutting-edge electrical component whose resistance depends on the amount of current that previously passed through it. Because it “remembers” this history even after charge is no longer flowing, it can store data when the power is switched off. In this way, memristors operate in a way remarkably similar to the neurons in our brains and the synapses connecting them.

With their fast response times, combined with simple, two-electrode structures that allow them to be packed into dense arrays, memristors are increasingly forming the building blocks of modern circuits—especially those designed for AI.

In 1874, German mathematician Georg Cantor published a groundbreaking paper showing that there are different sizes of infinity — a result that fundamentally changed mathematics by treating infinity as a concrete mathematical concept rather than a mere philosophical idea.

That paper became the foundation of set theory, a central pillar of modern mathematics.

Newly discovered letters from Cantor’s correspondence with fellow mathematician Richard Dedekind, believed lost until recently, suggest that a crucial part of the proof Cantor published came directly from Dedekind’s work.

Historian and journalist Demian Goos uncovered these letters while researching Cantor’s life. He found a key letter from November 30, 1873 that shows Dedekind’s proof of the countability of algebraic numbers — the same result Cantor would publish later under his own name.

Earlier histories had portrayed Cantor as a lone genius, but the new evidence reveals he relied heavily on Dedekind’s ideas and published them without proper credit, effectively erasing Dedekind’s role in the discovery.

Cantor’s strategy was partly tactical: because influential mathematician Leopold Kronecker vehemently opposed actual infinity, Cantor framed the paper under a less controversial title (about algebraic numbers), using Dedekind’s simplified methods to “sneak” in the revolutionary idea of comparing infinities.

The result was not just a new theorem but a new way of thinking about infinity, setting the stage for set theory and reshaping mathematics — even though the true story of its origins was more collaborative and ethically complicated than commonly told.

Conventional electronics process information leveraging the electrical charge of electrons. Over the past few decades, some electronics engineers have been exploring the potential of a different type of device that instead processes and stores data exploiting the intrinsic magnetic moment (i.e., spin) of electrons.

These devices, known as spintronics, could consume less energy, process data faster and be easier to reduce in size than current electronics. A central objective for engineers who are developing spintronics is to identify promising strategies to control magnetism in devices without wasting power.

One promising approach to control magnetism entails the use of multiferroics, materials that exhibit both ferroelectricity, meaning that positive and negative charges in them are permanently separated, and ferromagnetism, which means that magnetic moments in them are aligned. When one of these properties can be used to control the other, this is known as magnetoelectric coupling.

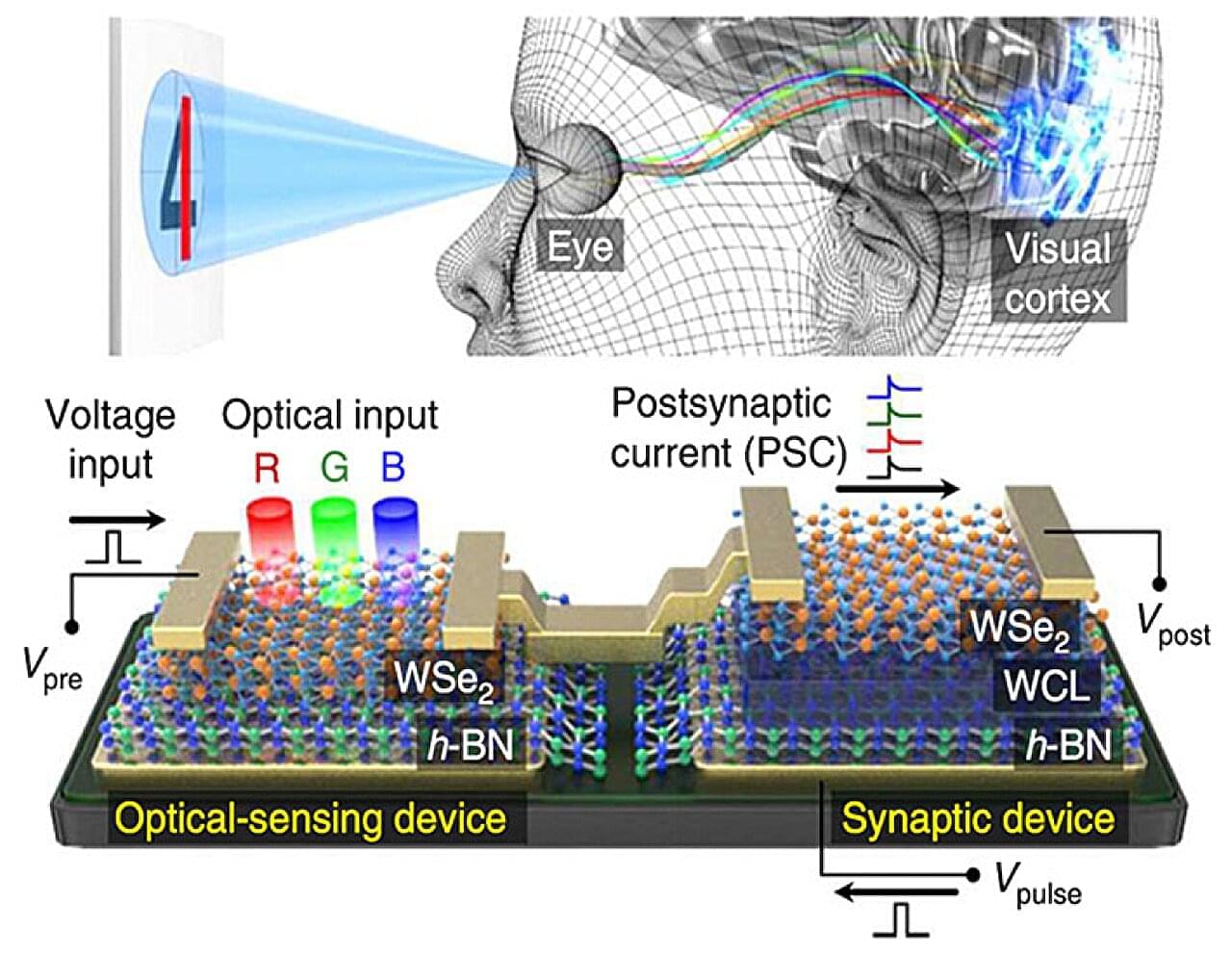

In physics, the classical “Hall effect,” discovered in the late 19th century, describes how a transverse voltage is generated when an electric current is exposed to a perpendicular magnetic field. Simply put, the magnetic field causes the electrons, which are negatively charged, to drift sideways, creating a negative charge on one edge of the conducting strip and a positive charge on the opposite side.

For decades, this voltage difference has been used as a diagnostic tool to measure magnetic fields with precision and characterize material doping levels, that is, the addition of a tiny, controlled amount of impurity to a pure material to change how it conducts electricity.

In the 1980s, experiments at ultra-low temperatures with ultra-thin conductors—imagine a sheet of paper—revealed that under intense magnetic fields, this voltage difference increases not in a straight line but in perfectly defined steps.

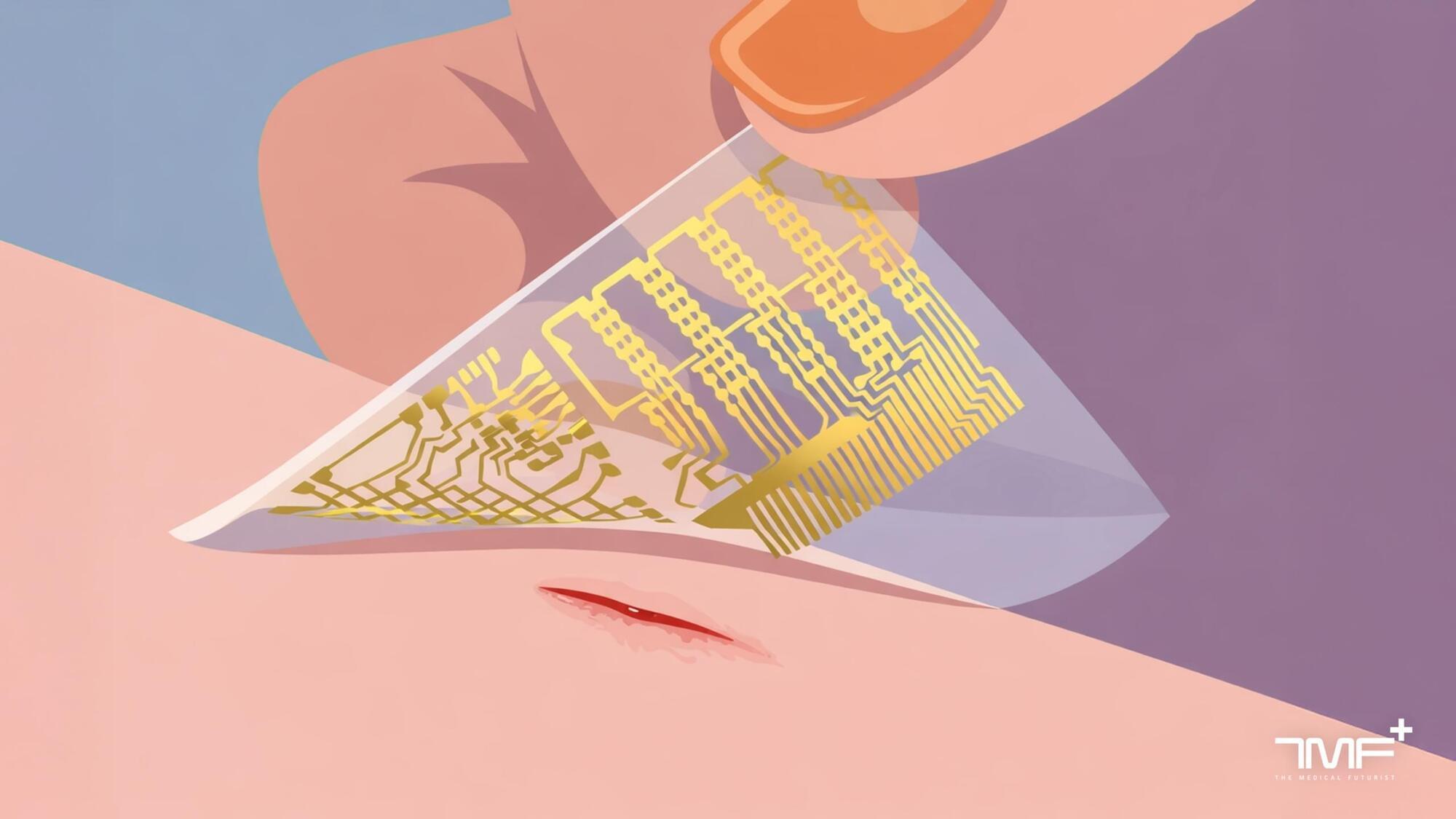

Unless you’ve been extremely lucky, you’ve likely been wounded, be it a knife cut while cooking or a sports injury. To remedy this unpleasant experience, you’ve taken some version of the following steps: clean the wound, disinfect the area, and apply a plaster or bandage. While a common and simple first-aid skill, this wound healing process has existed since ancient times.

Furthermore, there are wound cases, especially chronic wounds that arise from conditions such as diabetes, that can be more severe than one might expect. The 5-year survival rate of patients with chronic wounds is about 70%, which is worse than that of breast cancer, prostate cancer and other diseases. In addition, treating wounds adds to the cost of care, leading to about $28 billion per year in the U.S. alone.

Following the traditional use case, the main function of bandages for acute or chronic wound care has been to protect the injured area from external factors that could worsen the injury, such as dirt, bacterial infection and friction. Over the centuries since the inception of wound dressing, some changes have taken place. These have mostly related to the material of bandages, such as stronger-adhering waterproof ones; but the role of the bandage has retained its passive role.

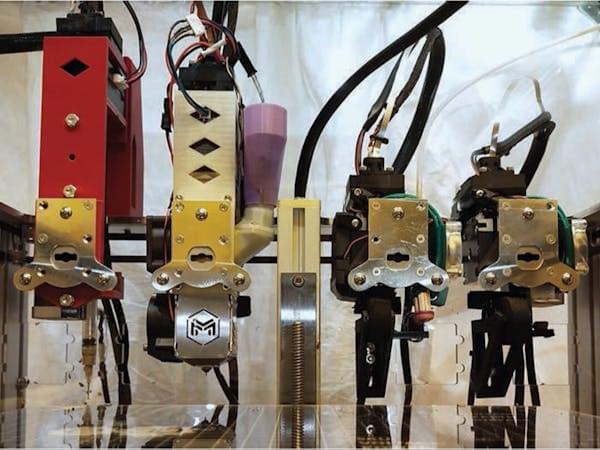

3D printers are not Star Trek-style replicators. Most 3D printers can only fabricate parts in a single material and that material is usually some form of plastic. But multi-material 3D printers do exist and by taking that idea to its limits, a team of researchers at MIT was able to build this 3D printer that can produce complete and functional electric motors.

The team didn’t have to start from scratch, because they were able to use an E3D ToolChanger 3D printer as the foundation for this project. That printer model came out several years ago and is now discontinued, but it was and still is pretty unique. It can swap between toolheads on-the-fly to print with different materials, which is a capability most users take advantage of to print with multiple colors or multiple kinds of thermoplastic filament material, such as PLA and PETG.

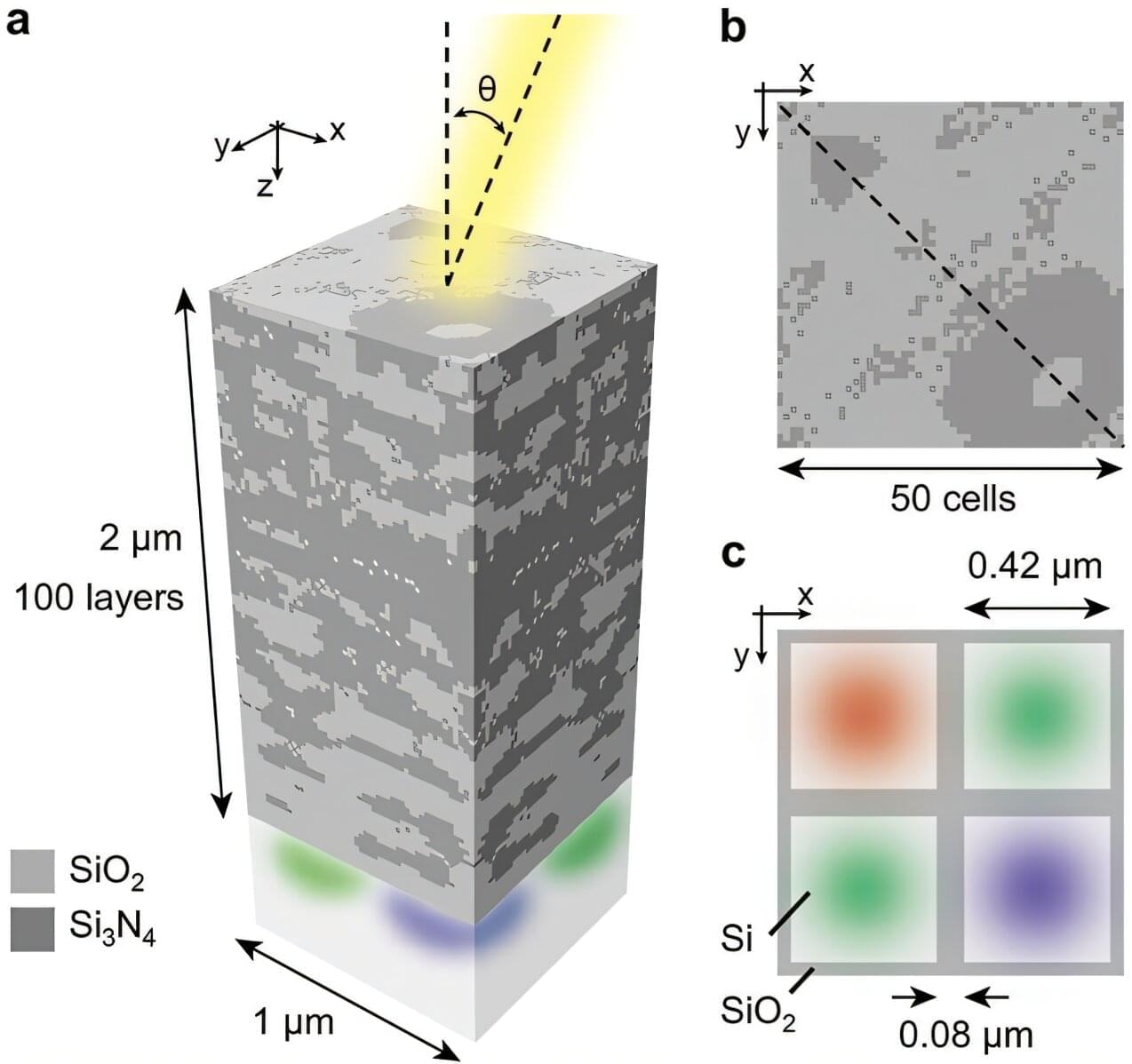

Smartphone cameras are becoming smaller, yet photos are becoming sharper. Korean researchers have elevated the limits of next-generation smartphone cameras by developing a new image sensor technology that can accurately represent colors regardless of the angle at which light enters. The team achieved this by utilizing a “metamaterial” that designs the movement of light through structures too small to be seen with the naked eye.

A research team led by Professor Min Seok Jang of the School of Electrical Engineering, in collaboration with Professor Haejun Chung’s team at Hanyang, has developed a metamaterial-based technology for image sensors that can stably separate colors even when the angle of light incidence varies.

The findings were published in Advanced Optical Materials.

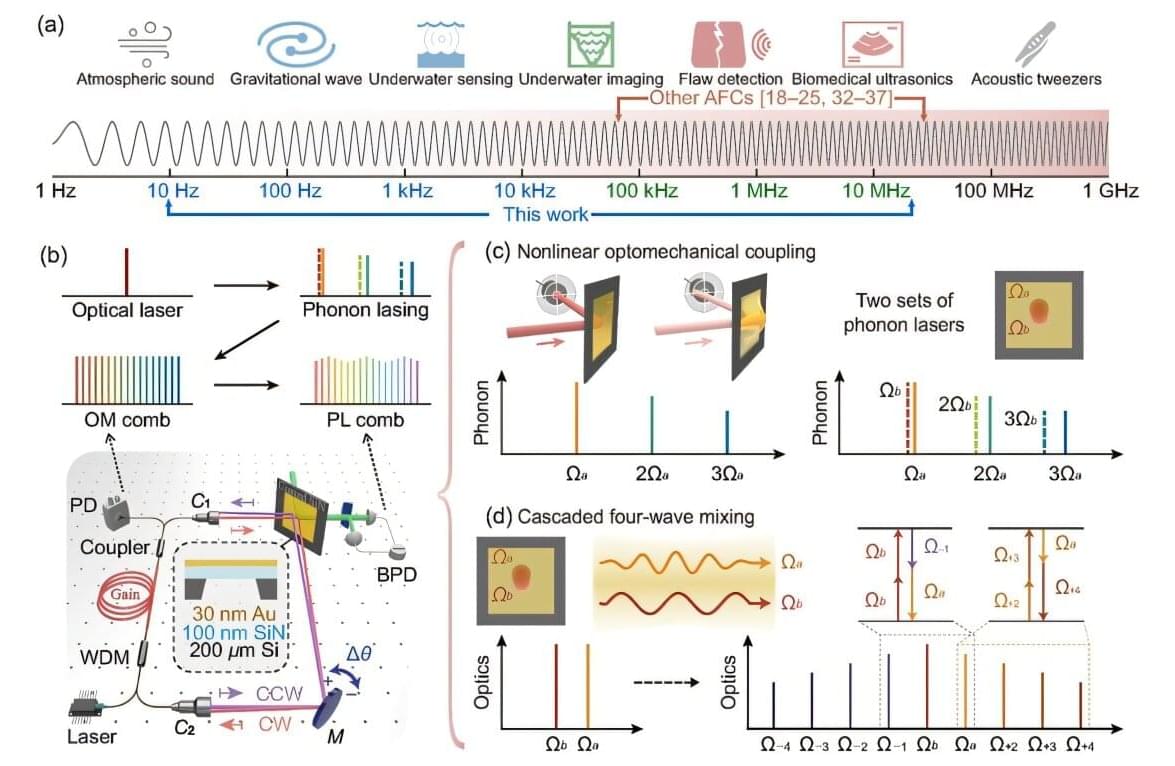

Acoustic frequency combs organize sound or mechanical vibrations into a series of evenly spaced frequencies, much like the teeth on a comb. They are the acoustic counterparts of optical frequency combs, which consist of equally spaced spectral lines and act as extraordinarily precise rulers for measuring light.

While optical frequency combs have revolutionized fields such as precision metrology, spectroscopy, and astronomy, acoustic frequency combs utilize sound waves, which interact with materials in fundamentally different ways and are well-suited for various sensing and imaging applications.

However, existing acoustic frequency combs operate only at very high, inaudible frequencies above 100 kHz and typically produce no more than a few hundred comb teeth, limiting their applicability.