Many cutting-edge technologies, ranging from augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) to LiDAR (light detection and ranging) systems, rely on components that enable the precise control of light. These components include so-called spatial light modulators (SLMs), systems that dynamically adjust the position of a light wave within its cycle (i.e., phase), as well as its amplitude or direction across several pixels.

Conventional SLMs rely on liquid crystals, materials in a state of matter at the intersection between solid and liquid. While these components are widely used, they typically struggle to reach the speed and pixel density required to create high-quality three-dimensional (3D) images known as holographs.

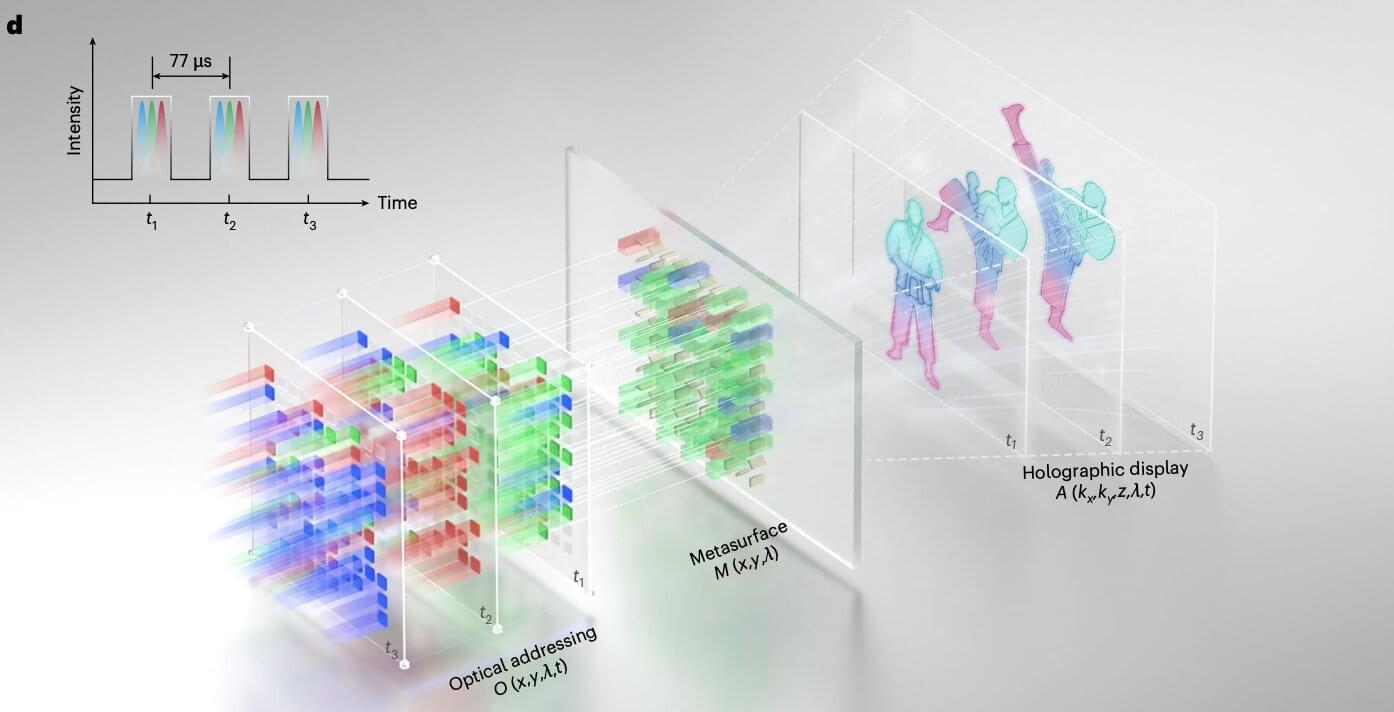

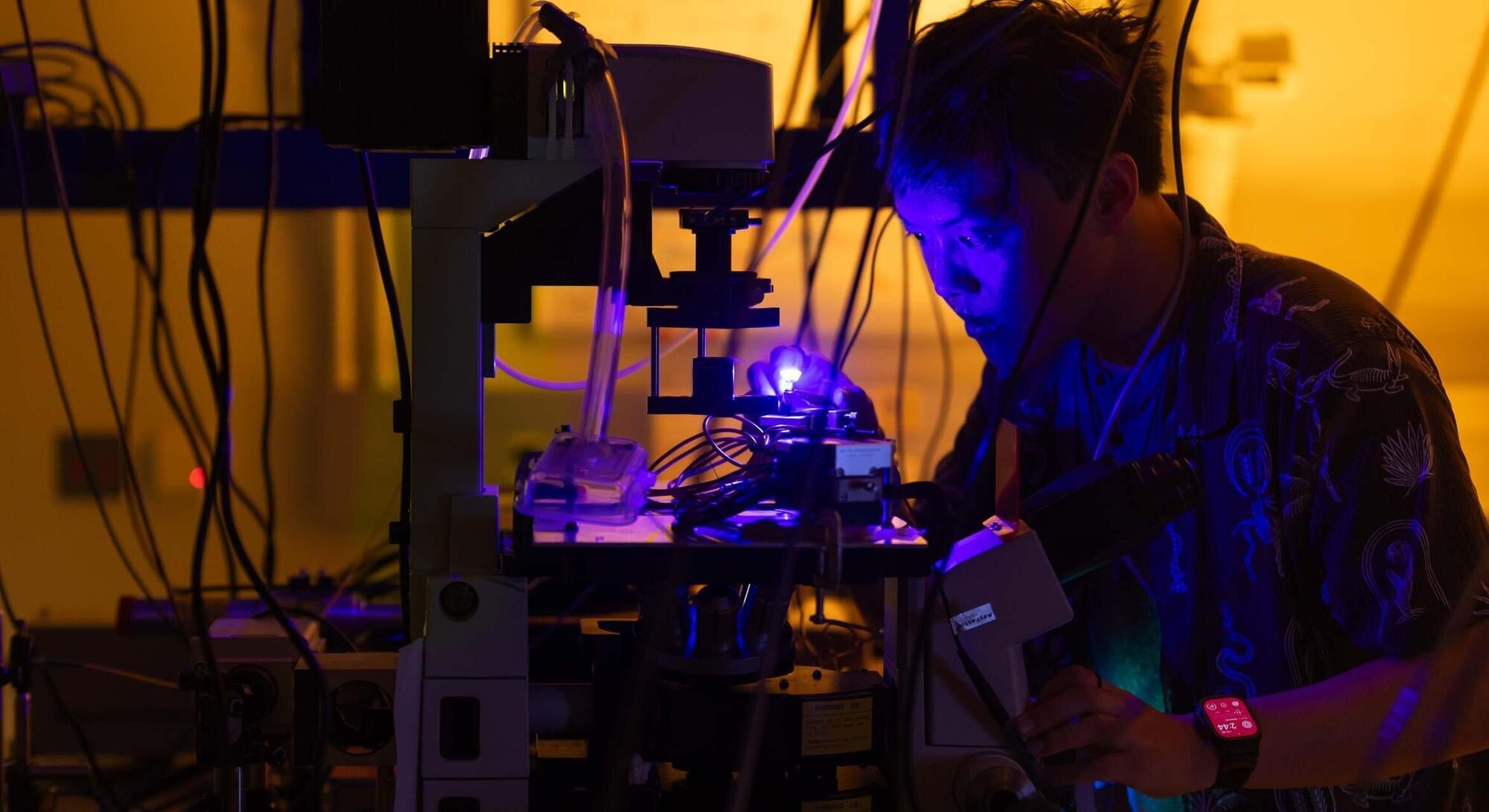

Researchers at Huazhong University of Science and Technology and other institutes recently developed a new metasurface, an ultrathin and nano-engineered surface, that could be used to produce dynamic and high-quality holographic images in real time, with a remarkable definition. The new metasurface, introduced in a paper published in Nature Nanotechnology, was used to create a SLM that could be used to enhance the performance of AR, VR, and LiDAR technology.