Daily reflection is a way to apply this principle in our everyday lives. It shines a spotlight on the behavior itself. And when behavior is observed consistently, it solidifies into neural pathways in the brain. We start behaving differently, not because someone else is judging us, but because we are measuring ourselves. The simple act of asking ourselves reflective questions each day shapes the behaviors in our lives, which, in turn, make us the people who exhibit those behaviors.

Another principle from quantum theory, entanglement, might also be at play when we do daily reflection. Quantum entanglement describes how particles can become linked to one another so that a change in one results in a change in the other. In the same way, the effort we make to change in one part of our lives is rarely confined to that part. Instead, our behaviors extend outward and affect those in relationship to us and around us. For example, your attempt to speak in positive terms, rather than negative ones, can influence your colleagues at work. Your intention to control your emotional outbursts can affect your family. Your efforts to build positive relationships at work or in your community can change the dynamics of those relationships. And when you combine these intentions with daily reflection, you’re not only strengthening a positive personal trait within yourself, but also influencing the bigger, interpersonal systems around you.

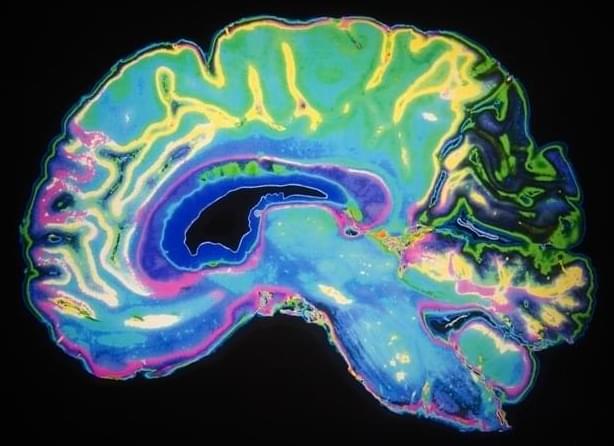

Philosophers, physicians, and physicists are forever debating what consciousness is. Is who we are just a byproduct of biology and the brain’s physiology, or is who we are more fundamental and exists irrespective of the brain’s neural firing? We may never know. That said, one thing is true: Conscious awareness shapes who we are. Without reflection, behavior defaults to habit. With reflection, possibility re-enters the system. The practice of asking yourself daily reflective questions puts you in the role of an observer rather than an actor. And from there, you can be intentional about who you choose to be tomorrow.