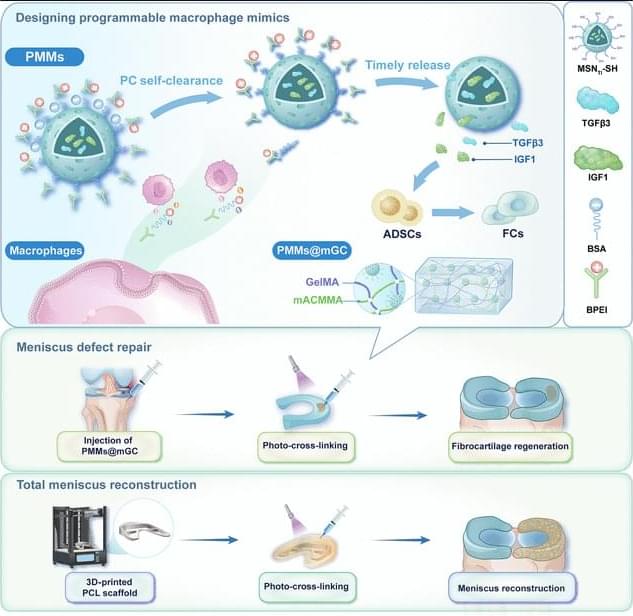

JUST PUBLISHED: programmable macrophage mimics for inflammatory meniscus regeneration via nanotherapy

Click here to read the latest free, Open Access Article from Research.

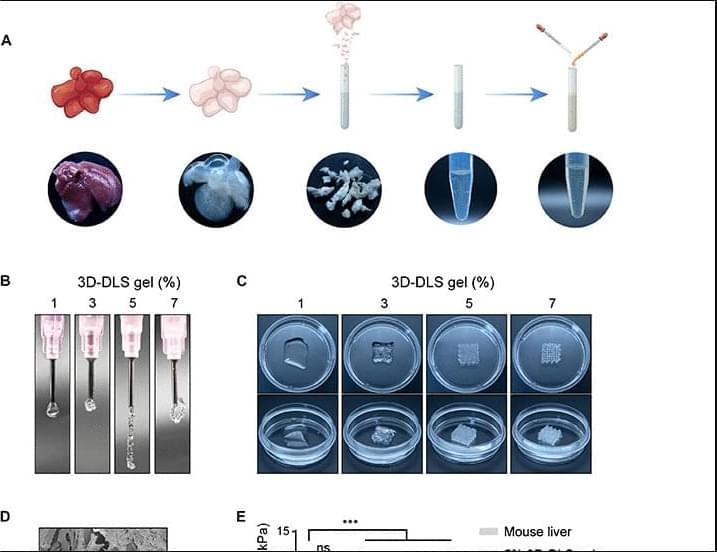

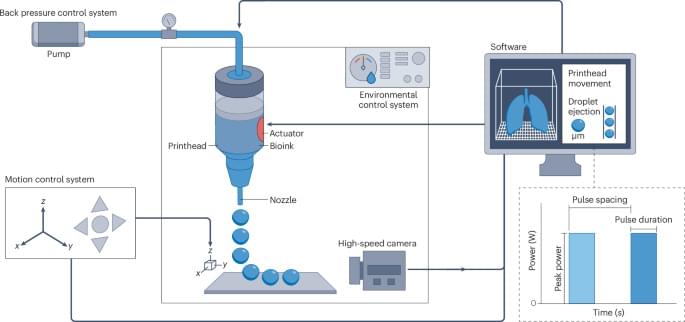

The meniscus is a fibrocartilaginous tissue and organ in the human knee joint that serves critical functions, including load transmission, shock absorption, joint stability, and lubrication. Meniscal injuries are among the most common knee injuries, typically caused by acute trauma or age-related degeneration [1– 3]. Minor meniscal injuries are usually treated with in situ arthroscopic procedures or conservative methods, whereas larger or more severe injuries often necessitate total meniscus replacement. Recent advances in materials science and manufacturing techniques have enabled transformative tissue-engineering strategies for meniscal therapy [4, 5]. Several stem cell types, including synovium-derived mesenchymal stem cells, bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells, and adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs), have been investigated as candidate seed cells for meniscal regeneration and repair. Notably, ADSCs are clinically promising because of their ease of harvest, high inducibility, innate anti-inflammatory properties, and potential to promote fibrocartilage regeneration [6– 8]. Our group has developed a series of decellularized matrix scaffolds for auricular, nasal, tracheal, and articular cartilage repair using 3-dimensional (3D) bioprinting techniques, successfully repairing meniscus defects and restoring physiological function [9– 12]. However, current tissue-engineering strategies for meniscus defect repair commonly rely on a favorable regenerative microenvironment. Pathological conditions such as osteoarthritis (OA) [13 – 16], the most prevalent joint disorder, often create inflammatory environments that severely hinder meniscus regeneration [17 – 21]. Moreover, meniscal injury exacerbates the local inflammatory milieu, further impeding tissue healing and inevitably accelerating OA progression. Therefore, there is an urgent need to establish a cartilaginous immune microenvironment that first mitigates early-stage inflammation after meniscal injury and then sequentially promotes later-stage fibrocartilage regeneration [22 – 25].

Currently, targeted regulation using small-molecule drug injections is commonly employed to treat inflammatory conditions in sports medicine [26,27]. Most of these drugs exhibit broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory effects and inevitably cause varying degrees of side effects by activating nonspecific signaling pathways. Polyethyleneimine is a highly cationic polymer. It is widely used to modulate inflammation by adsorbing and removing negatively charged proinflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and interleukin-6 (IL-6), via electrostatic interactions [28–31]. Notably, modifying polyethyleneimine into its branched form (branched polyethyleneimine [BPEI]) has been shown to improve cytocompatibility and enhance in vivo metabolic cycling.