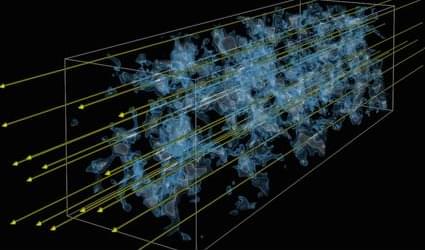

A new mathematical framework based on perturbation theory could yield new insights into cosmic structure and fundamental physics.

In 2017, headlines around the world declared the simulation hypothesis dead. Physicists had debunked it, the articles said. We could all move on. There was one problem. The paper they cited never mentioned the simulation hypothesis. The debunking was invented by journalists who never read the research. And in the years since, the actual physics has gotten significantly worse.

This documentary follows that physics all the way down.

We begin with what really happened in 2017 — the Ringel-Kovrizhin paper, what it actually proved, and Scott Aaronson’s correction that nobody shared. Then we examine Nick Bostrom’s original 2003 trilemma, the real math behind it, and why two decades of attacks from Sean Carroll, Lisa Randall, and Sabine Hossenfelder have failed to break it. Every critique concedes something. Every attempted kill shot narrows the escape routes.

From there, we trace the physics of information through three remarkable lives. Konrad Zuse, who built the first programmable computer in his parents’ living room during the bombing of Berlin, then proposed in 1967 that the universe itself is a computation — and was ignored. John Archibald Wheeler, who lost his brother in World War Two and spent the rest of his life asking whether reality is built from information, condensing it into three words that changed physics: \.

Like us on Facebook for daily videos, updates, announcements, and much more: https://shorturl.at/tak4l.

Can biology be explained entirely in terms of chemistry and then physics? If so, that’s “reductionism.” Or are there “emergent” properties at higher levels of the hierarchy of life that cannot be explained by properties at lower or more basic levels?

Wear your support for the show with a Closer To Truth merchandise purchase: https://bit.ly/3P2ogje.

Philip Stuart Kitcher is a British philosopher who is the John Dewey Professor Emeritus of philosophy at Columbia University. He specialises in the philosophy of science, the philosophy of biology, the philosophy of mathematics, and more recently pragmatism.

Donate to help Closer To Truth continue exploring the world’s deepest questions without the need for paywalls: https://closertotruth.com/donate/

Closer To Truth, hosted by Robert Lawrence Kuhn and directed by Peter Getzels, presents the world’s greatest thinkers exploring humanity’s deepest questions. Discover fundamental issues of existence. Engage new and diverse ways of thinking. Appreciate intense debates. Share your own opinions. Seek your own answers.

Lightning formation and the conditions triggering it have long been shrouded in a cloud of mystery, but new research led by Penn State scientists is lifting the fog. Using mathematical calculations, the researchers have discovered that lightning-like discharge doesn’t require a storm cloud—it could be made inside everyday material on a lab bench. The study is published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

“We applied the same exact models that we use for lightning research but shrank down the scale to slightly larger than a deck of cards,” said Victor Pasko, professor of electrical engineering at Penn State and lead author on the paper. “We calculated that when supplied with a high-powered electron source, lightning can be triggered in everyday insulating materials like glass, acrylic and quartz.”

The team used detailed numerical simulations to show that lightning-like radiation bursts could form inside small solid blocks, under conditions achievable in the lab. The work, if proven experimentally, could have implications for more compact and potentially safer X-ray sources in doctors’ offices and security checkpoints, the researchers said. The primary benefit, however, would be to enable the study of a powerful natural phenomenon on a lab bench.

The first in a series of 4 lectures by Edward Frenkel filmed at MSRI, Berkeley and broadcast on the Japanese TV channel NHK in the Fall of 2015 in the “Luminous Classroom” series. The lectures went from elementary topics such as Pythagoras theorem, prime numbers and symmetries to Fermat’s last theorem and the general Langlands conjectures, and to the recent work connecting the Langlands Program to Quantum Physics. Even though the Intro is in Japanese, the lecture itself is in English.

There is an art project to display every possible picture. The project admits this will take a long time, because there are many possible pictures. But how many? We will assume the very common color model known as True Color, in which each pixel can be one of 224 ≅ 17 million distinct colors. The digital camera shown below left has 12 million pixels. We’ll also consider much smaller pictures: the array below middle, with 300 pixels, and the array below right with just 12 pixels. Shown are some of the possible pictures:

12,000,000 pixels 300 pixels 12 pixels.

Quiz: Which of these produces a number of pictures similar to the number of atoms in the universe?

Answer: An array of n pixels produces (17 million)n different pictures. (17 million)12 ≅ 1,086, so the tiny 12-pixel array produces a million times more pictures than the number of atoms in the universe!

How about the 300 pixel array? It can produce 102,167 pictures. You may think the number of atoms in the universe is big, but that’s just peanuts to the number of pictures in a 300-pixel array. And 12M pixels? 1,086,696,638 pictures. Fuggedaboutit!

So the number of possible pictures is really, really, really big. And the number of atoms in the universe is looking relatively small, at least as a number of combinations.

On counting combinations People often underestimate the number of combinations of things. I think there are two main reasons: Combinations of things are multiplicative, while collections of things are additive. If you see a line of 6 people, it is easy to visualize a line of 60 people—it is ten times longer. But even if you know that there are 720 different orderings (permutations) in which those 6 people can line up, there is no way you can visualize the number of orderings for 60 people, because it is—you guessed it—larger than the number of atoms in the universe. Big numbers are hard. Even with simple collections of things, it takes practice to get a real intuition for the difference between 6 million and 6 billion people. When it comes to combinations, growth is faster and therefore intuition fails earlier. Authors are sloppy. Doug Smith reports that the New York Times confused “million” and “billion” over a dozen times per year; other sources also make similar mistakes. See the book by Unix co-creator Brian Kernighan for more on this. So beware, and be sure to use some simple math to augment your intuition when dealing with combinations.

Editorial: A parent-led developmental intervention improved executive function at school age in preterm children, especially in disadvantaged settings, supporting early, home-based approaches for neurodevelopment.

In a report of a trial in JAMA Pediatr ics, Tarouco et al1 describe studying the effect of a parent-led enhanced developmental intervention (EDI) on executive function at school age among children born preterm in Porto Alegre, Brazil. The intervention took place from ages 7 months to 12 months, and children who received parent-led EDI performed significantly better than those in the usual care group across all 4 domains assessed, with the strongest effects noted for motor persistence and inhibition.2

Executive function refers to the set of higher-order cognitive processes involved in emotional self-regulation and independent goal-directed behavior.3 Specifically, executive function comprises 3 major facets, working memory, inhibitory control, and cognitive flexibility, which form the basis of critical processes such as reasoning, problem-solving, and planning.4 As Tarouco et al1 note, executive function has been found to be more important for school readiness than a child’s IQ or entry-level reading or math skills.5 Children born preterm are more likely to have deficits in executive function as a consequence of numerous factors, including brain injury and reduced brain volume in regions associated with executive functioning (cerebral white matter; frontal, parietal, and temporal cortices; basal ganglia; and cerebellum) compared with term-born controls; medical comorbidities associated with prematurity (eg, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, necrotizing enterocolitis, sepsis) causing further oxidative damage; and neurosensory impairments.6 These deficits lead to academic challenges with lower scores in mathematics, reading, spelling, and writing; increased risk of learning disabilities; and multiple challenges navigating the demands of daily life.7 Given these widespread consequences, interventions addressing executive function are crucial in mitigating developmental delays in preterm infants and improving school success and participation. The neonatal and early infancy periods represent a window of opportunity to leverage the developing brain’s neuroplasticity to enhance long-term social and academic development.8

The majority of studies on measuring and improving executive function have been conducted in high-income, typically Western, industrialized countries, which represent a small fraction of the global population.9 Environmental and cultural factors, including home familial structure, diet and nutrition, parenting styles, home enrichment, and early life experiences, can vary vastly between high-income settings and low-to-middle-income countries (LMICs). There are a dearth of data surrounding interventions tailored to improving executive function in LMICs and a limited understanding of the factors that are protective for early development. The study by Tarouco et al1 adds valuable data relevant to this need. Importantly, the study intervention demonstrated benefit among a study cohort with social disadvantage because the majority of participants were receiving governmental assistance and attending public schools and participant mothers were largely from low socioeconomic strata.

This script is a mind-bending follow-up to your first one. It moves from Physics into Metaphysics and Platonism, specifically exploring the Mathematical Universe Hypothesis (MUH).

Since this script is more philosophical and \.