Cancer often begins when the genetic instructions that guide our cells become scrambled, allowing cells to grow uncontrollably. Now, scientists at EMBL have developed an AI-powered system called MAGIC that can automatically spot and tag cells showing early signs of chromosomal trouble—tiny DNA-filled structures known as micronuclei that are linked to future cancer development.

Category: robotics/AI

AI social platforms like Moltbook are potential accelerators of existential risk that should be regulated as critical infrastructure

The temptation is to treat Moltbook-like systems as harmless curiosities, a kind of accelerated chatroom in which agents talk, play, and occasionally generate entertaining artifacts. That framing is historically consistent with how societies first encountered earlier general-purpose technologies. It is also a mistake. Over time, social networks for AI could come to function as unsupervised training grounds, coordination substrates, and selection environments. AI agents could amplify capabilities through mutual tutoring, tool sharing, and rapid iterative refinement. They could also amplify risks through emergent collusion, deception, and the creation of machine-native memes optimized not for human comprehension but for agent persuasion and control. Such a social network is, therefore, not merely a communication system. It is an engine for cultural evolution. If the participants are AIs, then the culture that evolves could well become both alien and strategically consequential.

To understand what could go wrong, it is helpful to separate near-term societal hazards from longer-term existential hazards, and then to note that Moltbook-like platforms blur the boundary between the two. The near-term hazards include influence operations, economic manipulation, cyber offense, and institutional destabilization. The longer-term hazards derive from the classic AI control problem: How humanity can remain safely in control while benefiting from a superior form of intelligence.

The critical point: AI social networks are not merely places where AIs interact. They are environments in which agents can compound their capabilities and coordinate at scale—and environments in which humans can lose control. The prudent response is to regulate these platforms more like critical infrastructure, prioritizing auditability and reversibility, including the ability to revoke permissions and freeze or roll back agent populations.

Faster cancer screening? New AI system offers a better way to detect abnormal cells

One way cancer specialists detect the disease is by examining cells and bodily fluids under a microscope, a time-consuming and labor-intensive process called cytology. It involves visually inspecting tens of thousands to one million cells per slide for subtle 3D morphological changes that might signal the onset of cancer. But AI offers an approach that is potentially faster and more accurate.

In a new study published in the journal Nature, researchers demonstrate an AI-powered 3D scanning system that can automatically sort through samples and identify abnormal cells with performance approaching that of human experts.

Building digital models The team developed a system called Whole-Slide Edge Tomography, which uses a scanner to capture a series of images at different depths to create a 3D digital model of every cell on a slide.

Human Skills That Will Matter When AI Can Do Almost Everything

People ask me this constantly.

At conferences. After keynotes. In the Q&A. In the parking lot on the way out.

What skills will matter when AI can do almost everything?

Here is the framing principle that governs my answer:

The skills that will matter most are not the skills AI does best. They are the skills AI cannot replicate — and the ones that become more valuable precisely because AI makes everything else cheap.

When answers are free, questions become priceless.

When content is infinite, context becomes everything.

Anthropic CEO raises unsettling possibility about AI: “20% probability”

Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei says in an interview that the company doesn’t know whether its artificial intelligence (AI) models are conscious.

In an episode of the Interesting Times podcast with New York Times columnist Ross Douthat, Amodei explained a number of technical aspects of Anthropic’s work before Douthat asked specifically whether Anthropic would believe an AI model if it said it was conscious.

“We don’t know if the models are conscious,” Amodei admitted.

“We are not even sure that we know what it would mean for a model to be conscious, or whether a model can be conscious. But we’re open to the idea that it could be.”

Anthropic releases a document called a “model card” along with its models, which puts into writing the, “capabilities, safety evaluations and responsible deployment decisions for Claude models.”

Douthat pointed out that in a model card released for Anthropic’s Claude Opus 4.6, the model, “did find occasional discomfort with the experience of being a product.”

Cool Qubits Make Faster Decisions

Classical machine learning has benefited several physics subfields, from materials science to medical imaging. Implementing machine-learning algorithms on quantum computers could expand their use to more complex problems and to datasets that are inherently quantum. Nayeli Rodríguez-Briones at the Technical University of Vienna and Daniel Park at Yonsei University in South Korea have now proposed a thermodynamics-inspired protocol that could make quantum machine-learning techniques more efficient [1].

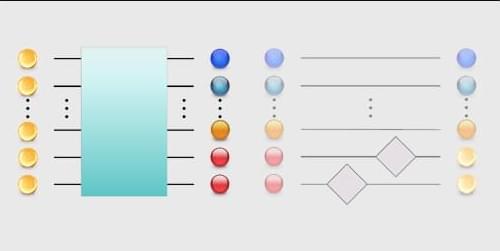

In one common classical machine-learning task, a system is trained on a known dataset and then challenged to classify new data. Its output quantifies both the classification and that classification’s uncertainty. Once the system’s parameters are fixed, evaluating the same data yields the same output. In contrast, the output of a quantum machine-learning algorithm is read out as binary measurements of qubits, which are inherently probabilistic. Because a single measurement provides only limited information, the computation must be repeated many times.

Rodríguez-Briones and Park recognized that how clearly a quantum computer reveals its output is determined by entropy. When the readout qubit is highly polarized—strongly favoring one outcome—its entropy is low. Few repetitions are needed to obtain a firm result. An unpolarized, high-entropy readout qubit returns both states more evenly, meaning more repetitions are required. The researchers showed that the readout qubit’s polarity can be increased by transferring its entropy to ancillary qubits, effectively cooling one while warming the others. Between runs, the ancillary qubits are reset by coupling them to a heat bath. Crucially, this entropy transfer affects the readout qubit’s degree of polarization without changing the encoded decision. The upshot: A given result can be arrived at with fewer repetitions.