Many central issues with which neurosciences is concerned, such as how we perceive the world around us, how we learn from experience, how we remember, how we direct our movements, and how we communicate with each other, have commanded the attention of thoughtful men and women for centuries. But it was not until after World War II that neuroscience began to emerge as a separate and increasingly vigorous scientific discipline that has as its ultimate objective providing a satisfactory account of animal (including human) behavior in biological terms. This ambitious goal has as its basis the central realization that all behavior is, in the last analysis, a reflection of the function of the nervous system. It is the organized and coordinated activity of the nervous system that ultimately manifests itself in the behavior of the organism. The challenge to neuroscience then, is to explain, in physical and chemical terms, how the nervous system marshalls its signaling units to direct behavior.

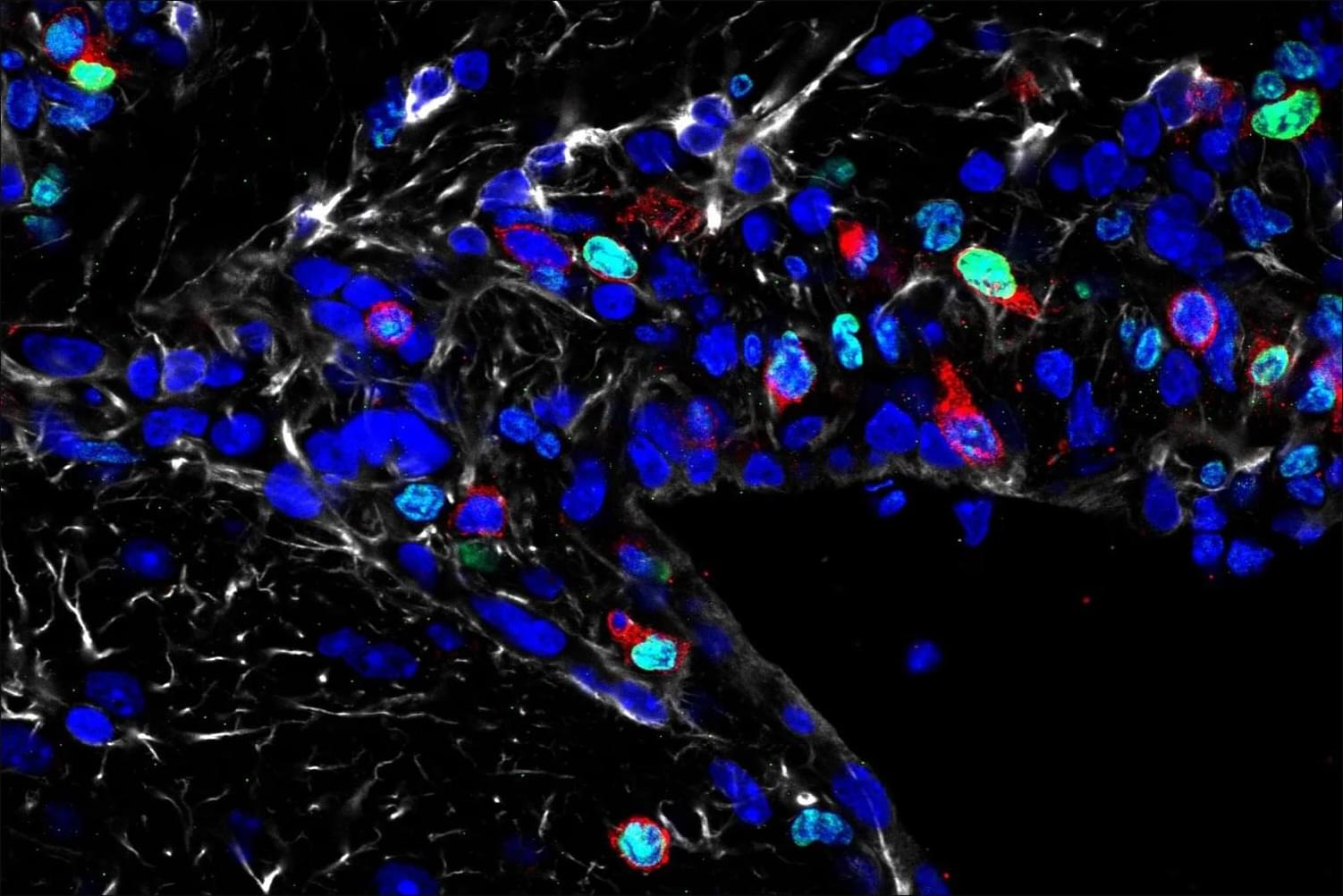

The real magnitude of this challenge can perhaps be best judged by considering the structural and functional complexity of the human brain and the bewildering complexity of human behavior. The human brain is thought to be composed of about a hundred billion (1011) nerve cells and about 10 to 50 times that number of supporting elements or glial cells. Some nerve cells have relatively few connections with other neurons or with such effector organs as muscles or glands, but the great majority receive connections from thousands of other cells and may themselves connect with several hundred other neurons. This means that at a fairly conservative estimate the total number of functional connections (known as synapses) within the human brain is on the order of a hundred trillion (1014). But what is most important is that these connections are not random or indiscriminate:

They constitute the essential “wiring” of the nervous system on which the extraordinarily precise functioning of the brain depends. We owe to the great neuroanatomists of the last century, and especially to Ramón y Cajal, the brilliant insight that cells with basically similar properties are able to produce very different actions because they are connected to each other and to the sensory receptors and effector organs of the body in different ways. One major objective of modern neuroscience is therefore to unravel the patterns of connections within the nervous system—in a word, to map the brain.