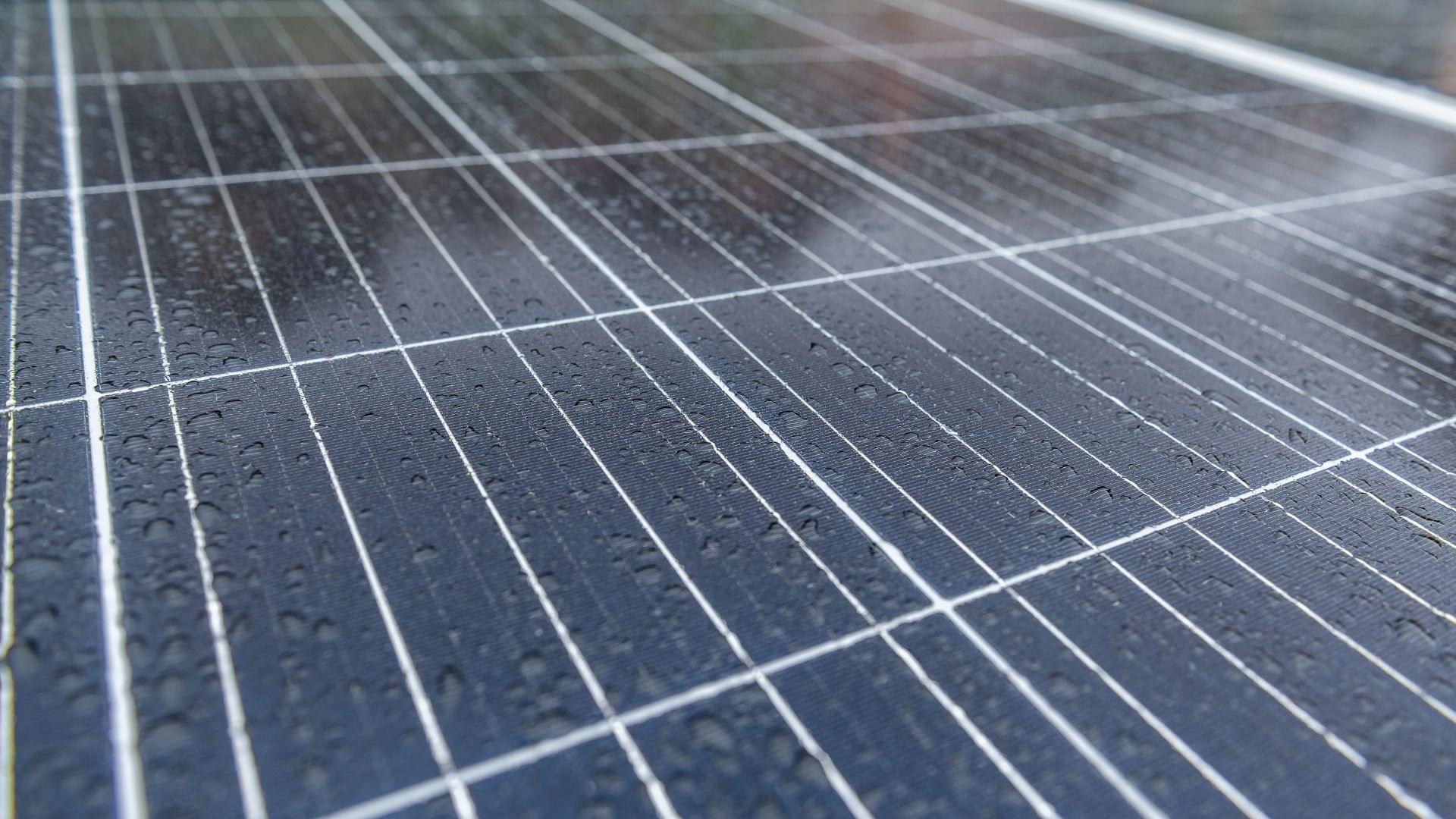

Research led by scientists at Washington State University has revealed insights on how plants form a microscopic landscape of proteins crucial to photosynthesis, the basis of Earth’s food and energy chain. The discovery provides a new view of the molecular engine that converts sunlight into bioenergy and could enable future fine-tuning of crops for higher yields and other useful traits.

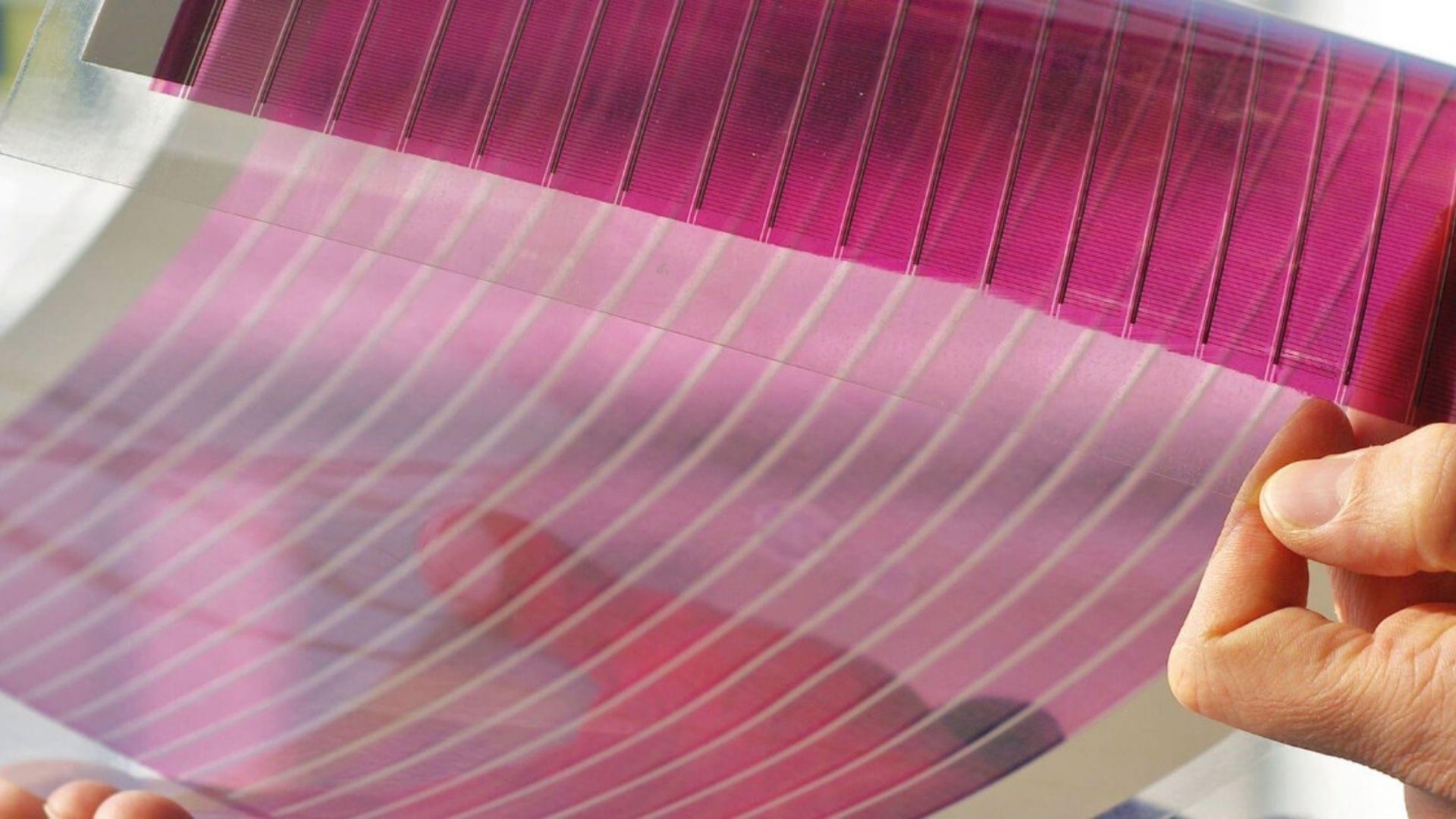

Colleagues at WSU, the University of Texas at Austin, and the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel used a novel, technology-powered approach to peer inside plant leaf cells and visualize the landscape of the photosynthetic membrane—the ribbon-like structure where plants harvest sunlight. The findings were recently published in the journal Science Advances.

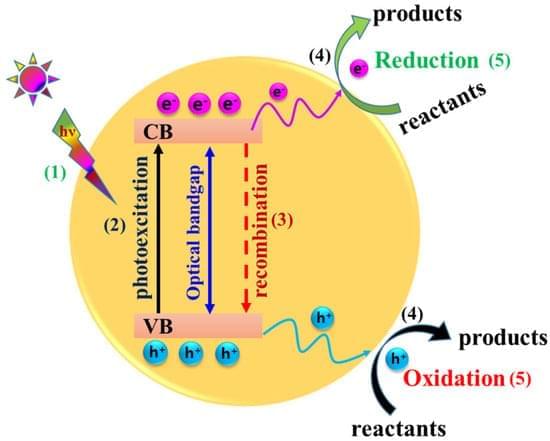

“These membranes are highly efficient biological solar cells,” said the study’s principal investigator and corresponding author, Helmut Kirchhoff. “They convert sunlight energy into chemical energy that fuels not only the plant’s metabolism but that of most life on Earth.”