With just a transistor and sensor coil, a new DIY motor achieves continuous motion without complex external electronics.

Category: electronics

The IceCube experiment is ready to uncover more secrets of the universe

The name “IceCube” not only serves as the title of the experiment, but also describes its appearance. Embedded in the transparent ice of the South Pole, a three-dimensional grid of more than 5,000 extremely sensitive light sensors forms a giant cube with a volume of one cubic kilometer. This unique arrangement serves as an observatory for detecting neutrinos, the most difficult elementary particles to detect.

In order to detect neutrinos, they must interact with matter, creating charged particles whose light can be measured. These light measurements can be used to determine information about the properties of neutrinos. However, the probability of neutrinos interacting with matter is extremely low, so they usually pass through it without leaving a trace, which makes their detection considerably more difficult.

For this reason, a large detector volume is required to increase the probability of interaction, and state-of-the-art technology is crucial for detecting such rare interactions.

IceCube upgrade adds six deep sensor strings to detect lower-energy neutrinos

Since 2010, the IceCube Observatory at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station has been delivering groundbreaking measurements of high-energy cosmic neutrinos. It consists of many detectors embedded in a volume of Antarctic ice measuring approximately one cubic kilometer. IceCube has now been upgraded with new optical modules to enable it to measure lower-energy neutrinos as well. Researchers at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) made a significant contribution to this expansion.

IceCube serves to measure high-energy neutrinos in an ice volume of one cubic kilometer. As neutrinos themselves do not emit any signals, the tracks of muons and other secondary particles are measured precisely. Muons are elementary particles sometimes produced by the interaction of neutrinos with ice. Contrary to neutrinos, muons carry an electric charge. On their way through the ice, they produce a characteristic light cone, which is detected by highly sensitive detectors.

Now, 51 researchers from around the world have installed six new strings of novel sensors up to 2,400 meters deep into the eternal ice, thereby expanding the IceCube experiment to also measure low-energy neutrinos.

New laser “comb” can enable rapid identification of chemicals with extreme precision

Researchers demonstrated a broadband infrared frequency comb that can operate stably, efficiently, and accurately without the need for bulky external components. The device could be utilized in a remote sensor or portable mass spectrometer that can track and monitor multiple chemicals in real-time for extended periods.

Time crystals could be used to build accurate quantum clocks

Once considered an oddity of quantum physics, time crystals could be a good building block for accurate clocks and sensors, according to new calculations.

Hair-thin silica fiber microphone detects ultrasound from 40 kHz to 1.6 MHz

Researchers have fabricated a hair-thin microphone made entirely of silica fiber that can detect a large range of ultrasound frequencies beyond the reach of the human ear. Able to withstand temperatures up to 1,000°C, the device could eventually be used inside high-voltage transformers to detect early signs of failure before power outages occur.

“Conventional electronic sensors often fail under thermal stress or suffer from severe signal interference,” said Xiaobei Zhang, a member of the research team from Shanghai University. “Our all-fiber microphone can survive in hazardous environments and is completely immune to electromagnetic interference while remaining sensitive enough to hear the subtle early warning signals of equipment failure.”

In an article published in Optics Express, the researchers describe their new microphone, which is sensitive to frequencies from 40 kHz to 1.6 MHz. Unlike traditional microphones that rely on bulky housing, the new microphone is entirely integrated within a fiber just 125 microns in diameter.

Listening to polymers collapse: ‘Water bridges’ pull the strings

It is not easy to follow the interactions of large molecules with water in real time. But this can be easier to hear than to see. This is how an international team deciphered the role of water in the collapse of PNIPAM.

Some polymers react to their environment with conformational changes: one of these is the polymer PNIPAM, short for poly(N-isopropylacrylamide). It is water-soluble below around 32 degrees Celsius, but above this temperature it precipitates and becomes hydrophobic. This qualifies it for smart sensor applications. But what actually happens between PNIPAM and the solvent water?

Researchers at Ruhr University Bochum, Germany, and the University of Illinois Urbana Champaign collaborated with sound production specialists from Symbolic Sound Corporation to investigate this question. Using sound representation, they were able to decipher the interaction of water molecules with PNIPAM for the first time. They reported their findings in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on February 4, 2026.

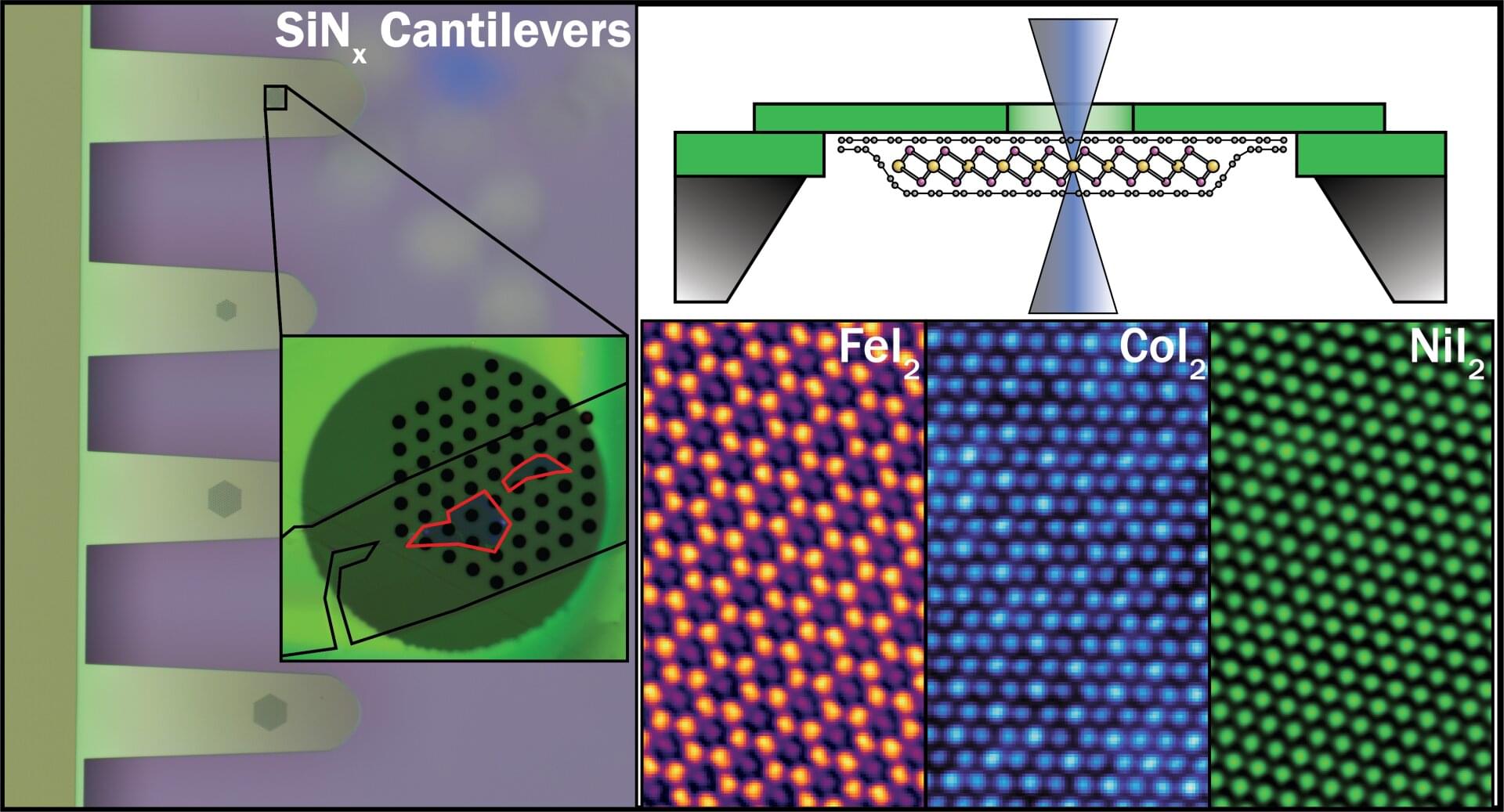

Graphene sealing enables first atomic images of monolayer transition metal diiodides

Two-dimensional (2D) materials promise revolutionary advances in electronics and photonics, but many of the most interesting candidates degrade within seconds of air exposure, making them nearly impossible to study or integrate into real-world technology. Transition metal dihalides represent a particularly compelling yet challenging class of materials, with predicted properties ideal for next-generation devices, but their extreme reactivity when exposed to air prevents even basic structural characterization.

Researchers at The University of Manchester’s National Graphene Institute have now achieved the first atomic-resolution imaging of monolayer transition metal diiodides, made possible by creating graphene-sealed TEM samples that prevent these highly reactive materials from degrading on contact with air.

The study, published in ACS Nano, demonstrates that fully encapsulating the crystals in graphene preserves atomically clean interfaces and extends their usable lifetime from seconds to months.