Delve into the groundbreaking world of CRISPR gene editing – a technology rapidly reshaping medicine and offering unprecedented hope for treating previously incurable diseases. This video explores the remarkable journey from basic scientific curiosity about bacterial defense mechanisms to the first-ever personalized gene therapies being administered in Germany and beyond.

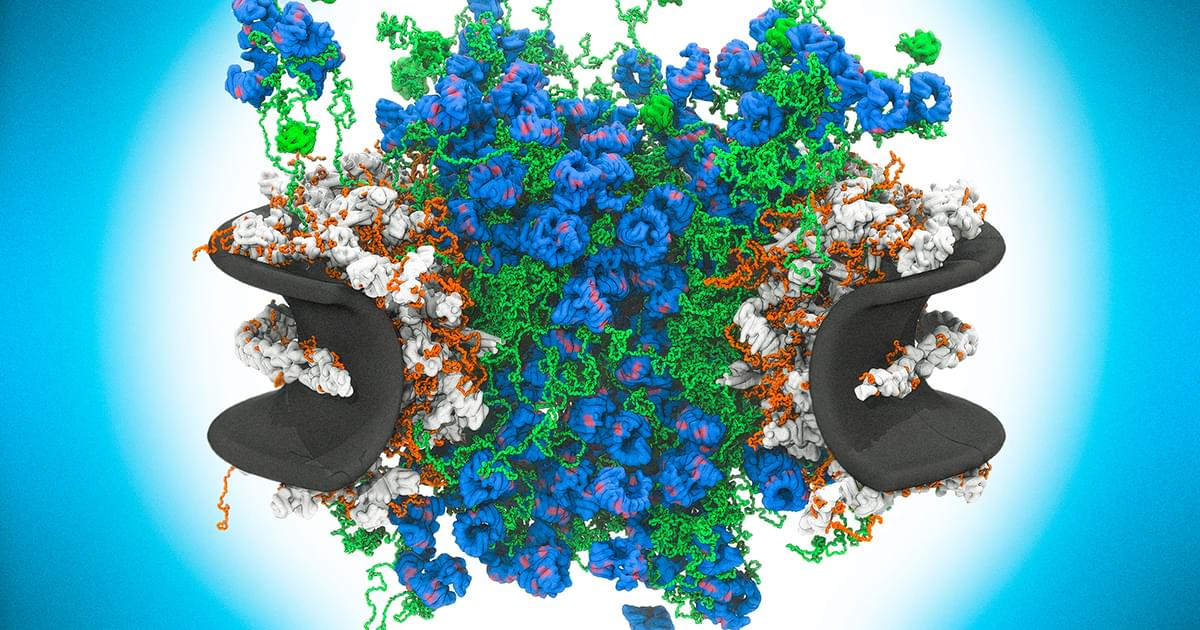

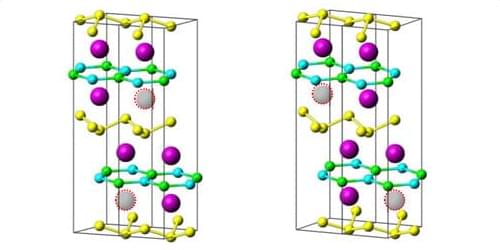

Discover how scientists uncovered CRISPR, an ancient bacterial immune system that functions as a precise molecular “cut-and-paste” tool for DNA. Learn about the astonishing speed at which this discovery transitioned from laboratory research to clinical applications, culminating in FDA approval of treatments for sickle cell disease and beta thalassemia – conditions once considered devastatingly difficult to manage.

We’ll examine the details of these revolutionary therapies, including how they work to correct genetic defects and provide lasting relief for patients. Beyond current successes, explore the exciting potential of CRISPR to address a wide range of inherited disorders, from hereditary angioedema to various cancers.

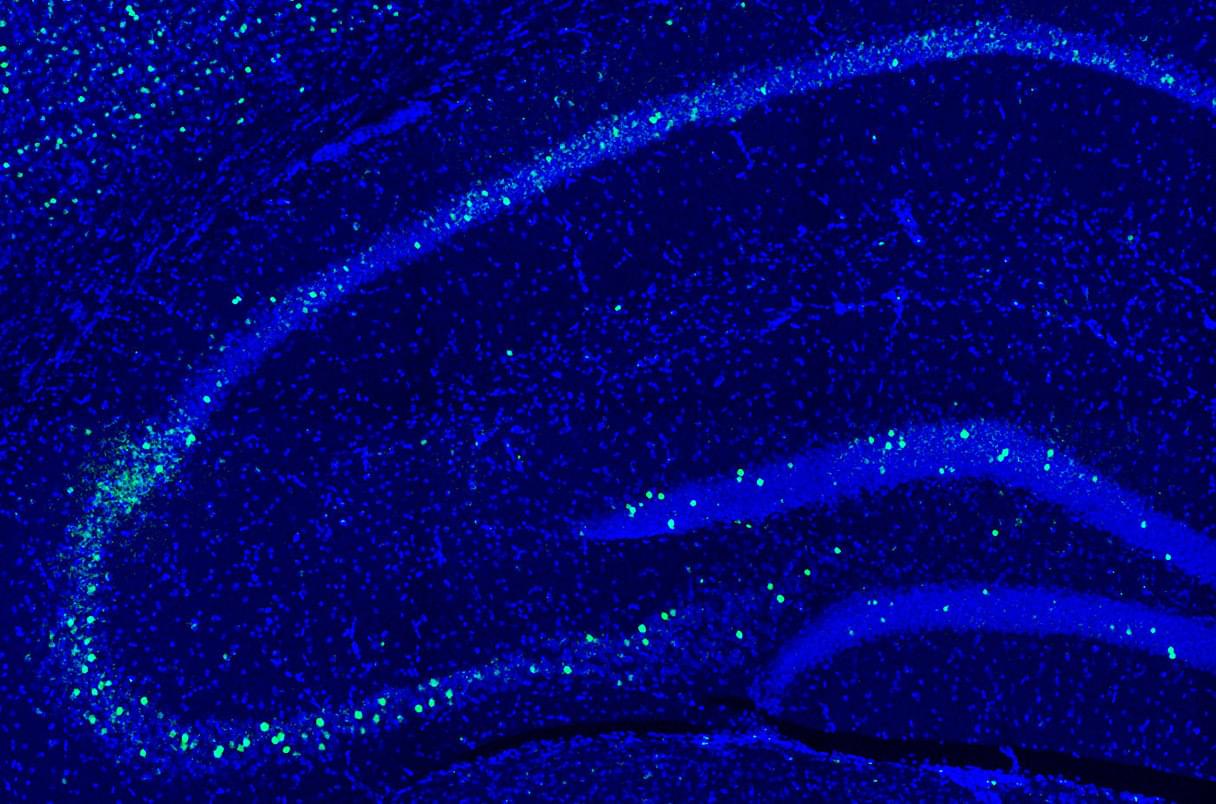

The video highlights the extraordinary case of KJ, an infant who received a custom-designed CRISPR base editing therapy to treat a rare metabolic disorder – demonstrating the feasibility of truly personalized medicine tailored to individual genetic profiles. Understand how this breakthrough compresses years of research into mere months, paving the way for treating countless other rare diseases.

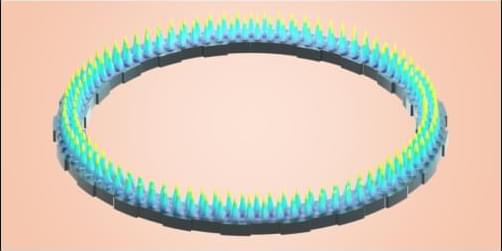

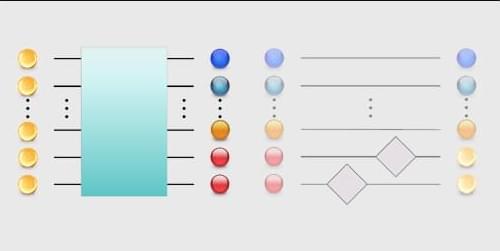

Finally, look ahead to the future with the emergence of TIGR systems, an even more advanced class of gene-editing tools discovered in viruses that infect bacteria. These next-generation technologies promise enhanced precision, broader targeting capabilities, and potentially safer therapeutic applications. Join us as we unpack this complex science and reveal how fundamental research continues to unlock the secrets of life and offer hope for a healthier future.

#genetherapy.