Discover the pivotal role of a single type of cell that sparked the incredible evolution from simple sea creatures of 800 million years ago to the diverse array of complex animals we see today.

The intricate relationship between hydrogen sulfide (H2S), gut microbiota, and sirtuins (SIRTs) can be seen as a paradigm axis in maintaining cellular homeostasis, modulating oxidative stress, and promoting mitochondrial health, which together play a pivotal role in aging and neurodegenerative diseases. H2S, a gasotransmitter synthesized endogenously and by specific gut microbiota, acts as a potent modulator of mitochondrial function and oxidative stress, protecting against cellular damage. Through sulfate-reducing bacteria, gut microbiota influences systemic H2S levels, creating a link between gut health and metabolic processes. Dysbiosis, or an imbalance in microbial populations, can alter H2S production, impair mitochondrial function, increase oxidative stress, and heighten inflammation, all contributing factors in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

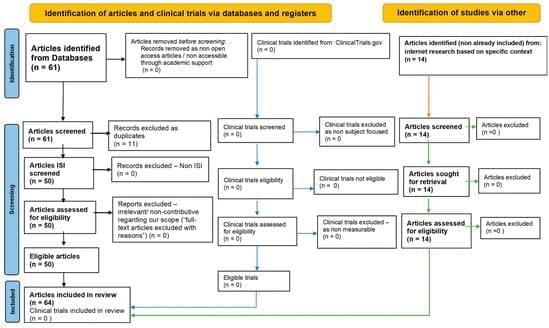

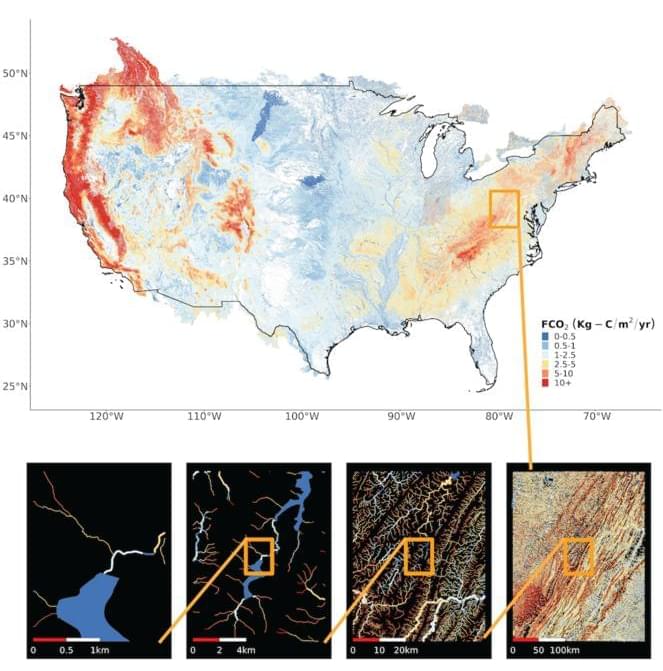

What is the level of carbon emissions across the United States? This is what a recent study published in AGU Advances hopes to address as a team of researchers from the University of Massachusetts Amherst conducted the first nationwide analysis of carbon emissions across the United States with the goal of putting constraints on previous analyses regarding the amount of carbon emissions across the United States, also known as the carbon cycle. This study holds the potential to help researchers, climate scientists, and the public better understand the United States’ contribution to climate change and the steps that can be taken to mitigate them.

“We need to know how much CO2 is being generated so we can predict how it will respond to climate change,” said Dr. Matthew Winnick, who is an assistant professor of Earth, Geographic and Climate Sciences at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and a co-author on the study. “As temperature rises, we tend to think that a lot of the natural carbon cycle processes will respond to that and potentially amplify climate change.”

For the study, the researchers collected data on carbon emissions across more than 22 million rivers, lakes, and water reservoirs with the goal of developing a model that could put tighter constraints on previous carbon cycle models. In the end, the researchers’ models estimated approximately 120 million metric tons of carbon, which is approximately 25 percent lower than previous models which estimated approximately 159 million metric tons of carbon. The researchers note these more accurate findings could benefit carbon capturing methods to mitigate climate change.

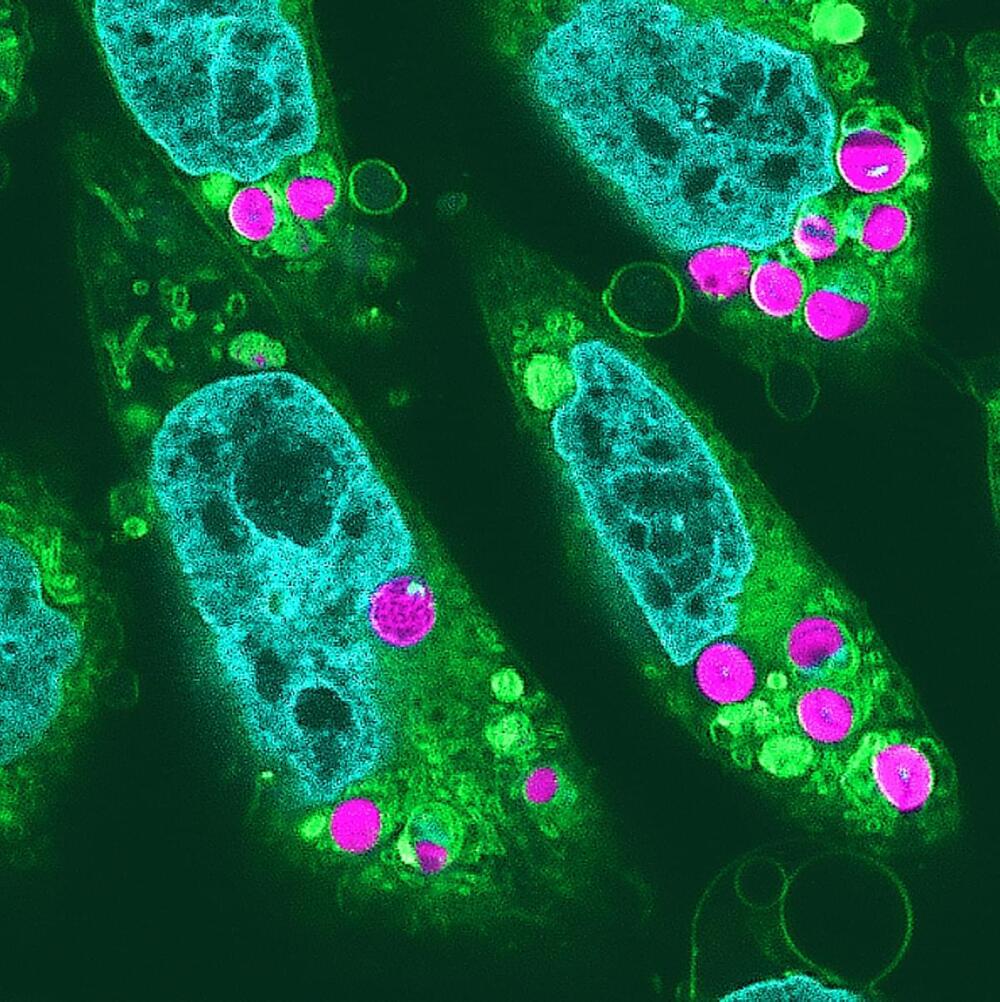

Scientists in Japan have created hybrid plant-animal cells, essentially making animal cells that can gain energy from sunlight like plants. The breakthrough could have major benefits for growing organs and tissues for transplant, or lab-grown meat.

Animal and plant cells have different energy-producing structures inside them. For animals, that’s mitochondria, which convert chemical energy from food into a form that our cells can use. Plants and algae, meanwhile, use chloroplasts, which perform photosynthesis to generate energy from sunlight to power their cells.

In a new study led by the University of Tokyo, the team inserted chloroplasts into animal cells, and found that they continued to perform photosynthetic functions for at least two days. The chloroplasts were sourced from red algae, while the animal cells were cultured from hamsters.

When lightning strikes, the electrons come pouring down.

In a new study, researchers at CU Boulder led by an undergraduate student have discovered a new link between weather on Earth and weather in space. The group used satellite data to show that lightning storms on our planet can knock especially high-energy, or “extra-hot,” electrons out of the inner radiation belt—a region of space filled with charged particles that surrounds Earth like an inner tube.

The team’s results could help satellites and even astronauts avoid dangerous radiation in space. This is one kind of downpour you don’t want to get caught in, said lead author Max Feinland.

Researchers at Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden and at the University of Magdeburg in Germany have developed a novel type of nanomechanical resonator that combines two important features: high mechanical quality and piezoelectricity. This development could open doors to new possibilities in quantum sensing technologies.

Dell Technologies expands its computing (HPC) portfolio, offering powerful solutions to help organizations quickly innovate with confidence.

With a range of new offers, Dell delivers technologies and services to help power demanding applications while making HPC capabilities more accessible to businesses.

Dell PowerEdge servers champion advanced modeling and datasets.