‘Three Nines’ Surpassed: Quantinuum Notches Milestones For Hardware Fidelity And Quantum Volume Formed in 2021, Quantinuum is the combination of the quantum hardware team from Honeywell Quantum Solutions (HQS) and the quantum software team at Cambridge Quantum Computing, HQS was founded in 2014.

Quantinuum has raised the bar for the global ecosystem by achieving the historic and much-vaunted “three 9’s” 2-qubit gate fidelity in its commercial quantum computer and announcing that its Quantum Volume has surpassed one million – exponentially higher than its nearest competitors.

By Ilyas Khan, Founder and Chief Product Officer, Jenni Strabley, Sr Director of Offering Management

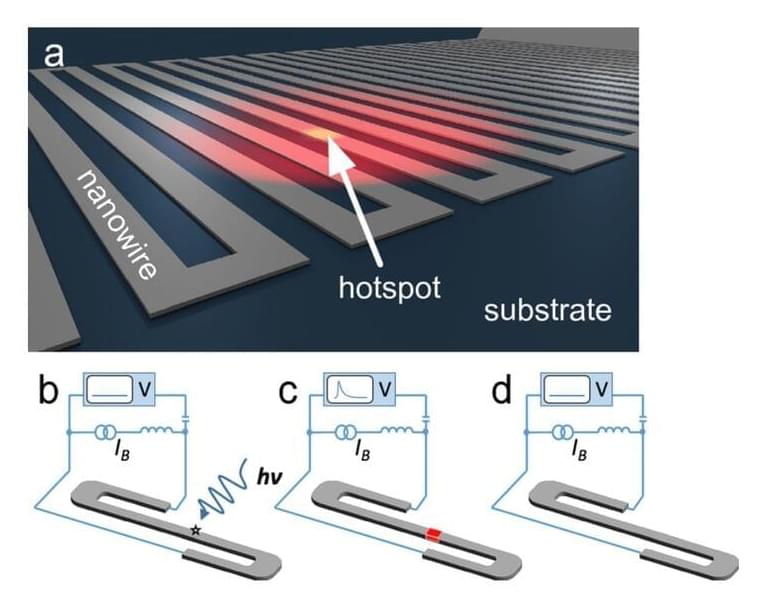

All quantum error correction schemes depend for their success on physical hardware achieving high enough fidelity. If there are too many errors in the physical qubit operations, the error correcting code has the effect of amplifying rather than diminishing overall error rates. For decades now, it has been hoped that one day a quantum computer would achieve “three 9’s” – an iconic, inherent 99.9% 2-qubit physical gate fidelity – at which point many of the error-correcting codes required for universal fault tolerant quantum computing would successfully be able to squeeze errors out of the system.