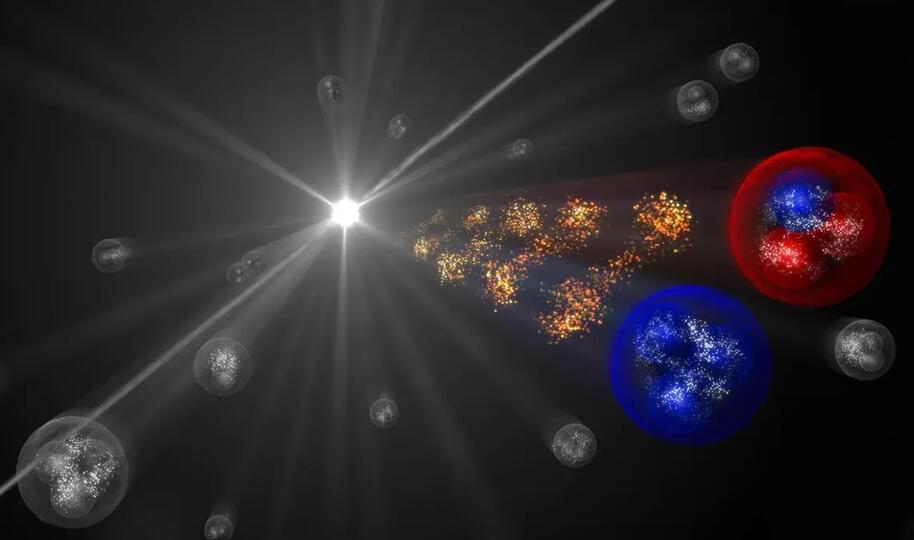

The quantum entanglement of particles is now an established art. You take two or more unmeasured particles and correlate them in such a way that their properties blur and mirror each other. Measure one and the other’s corresponding properties lock into place, instantaneously, even when separated by a wide distance.

In new research, physicists have theorized a bold way to change it up by entangling two particles of very different kinds – a unit of light, or a photon, with a phonon, the quantum equivalent of a wave of sound.

Physicists Changlong Zhu, Claudiu Genes, and Birgit Stiller of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Light in Germany have called their proposed new system optoacoustic entanglement.