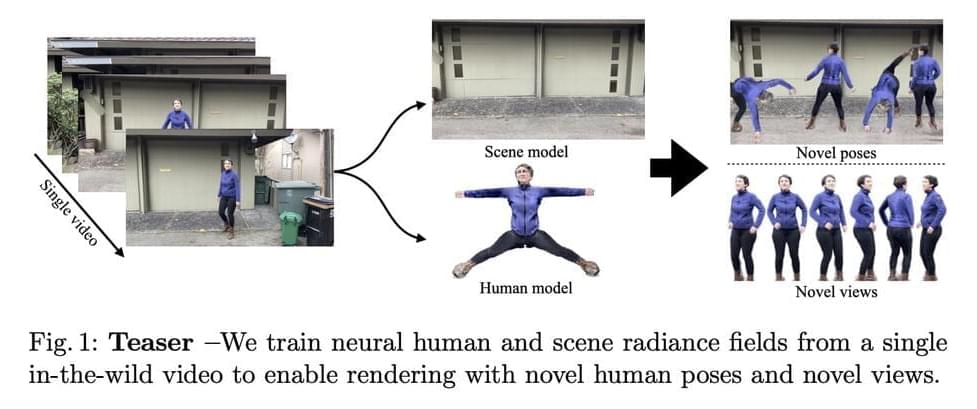

Neural Radiance Fields (NeRF) were first developed, greatly enhancing the quality of new vision synthesis. It was first suggested as a way to rebuild a static picture using a series of posed photographs. However, it has been swiftly expanded to include dynamic and uncalibrated scenarios. With the assistance of sizable controlled datasets, recent work additionally concentrate on animating these human radiance field models, thereby broadening the application domain of radiance-field-based modeling to provide augmented reality experiences. In this study, They are focused on the case when just one video is given. They aim to rebuild the human and static scene models and enable unique posture rendering of the person without the need for pricey multi-camera setups or manual annotations.

Neural Actor can create inventive human poses, but it needs several films. Even with the most recent improvements in NeRF techniques, this is far from a simple task. The NeRF models must be trained using many cameras, constant lighting and exposure, transparent backgrounds, and precise human geometry. According to the table below, HyperNeRF cannot be controlled by human postures but instead creates a dynamic scene based on a single video. ST-NeRF uses many cameras to rebuild each person using a time-dependent NeRF model, although the editing is only done to change the bounding box. HumanNeRF creates a human model from a single video with masks that have been carefully annotated; however, it does not demonstrate generalization to novel postures.

With a model trained on a single video, Vid2Actor can produce new human poses, but it cannot model the surroundings. They solve these issues by proposing NeuMan, a system that can create unique human stances and novel viewpoints while reconstructing the person and the scene from a single in-the-wild video. Figure 1’s high-quality pose-driven rendering is made possible by NeuMan, a cutting-edge framework for training NeRF models for both the human and the scene. They first estimate the camera poses, the sparse scene model, the depth maps, the human stance, the human form, and the human masks from a moving camera’s video.