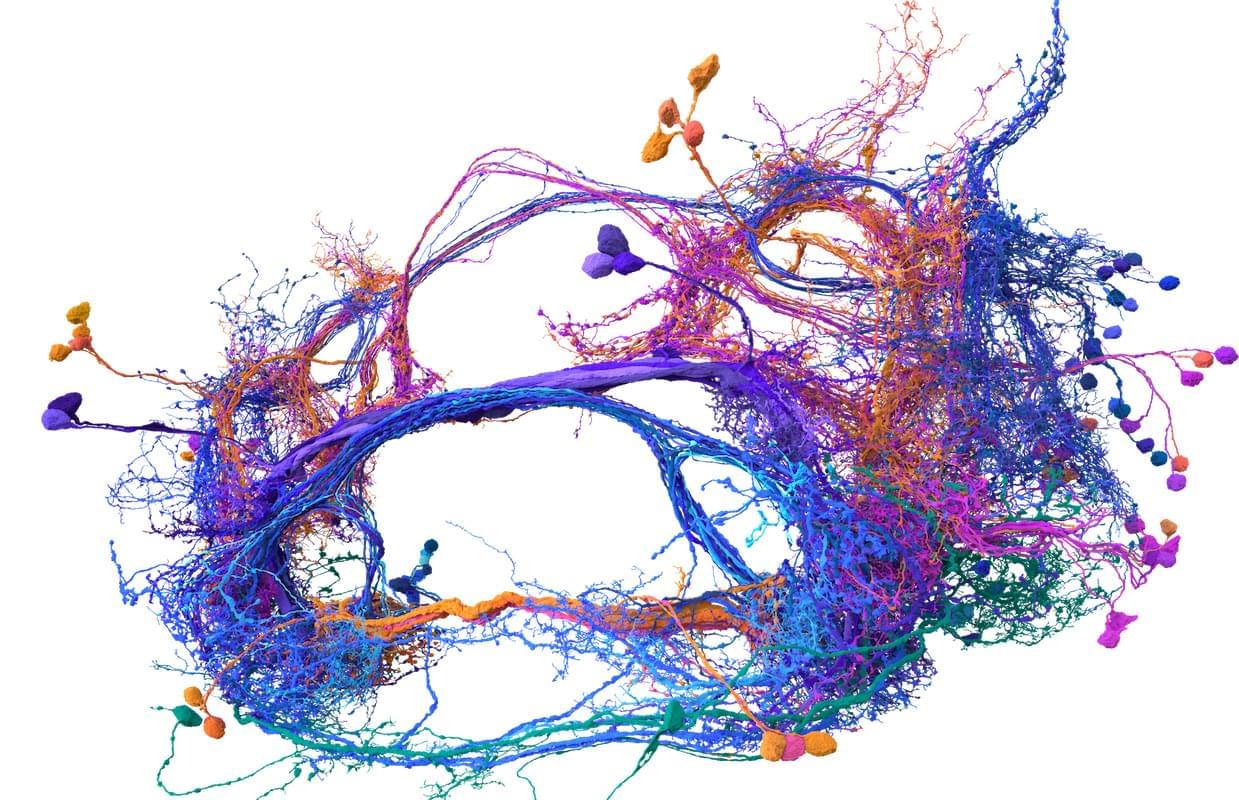

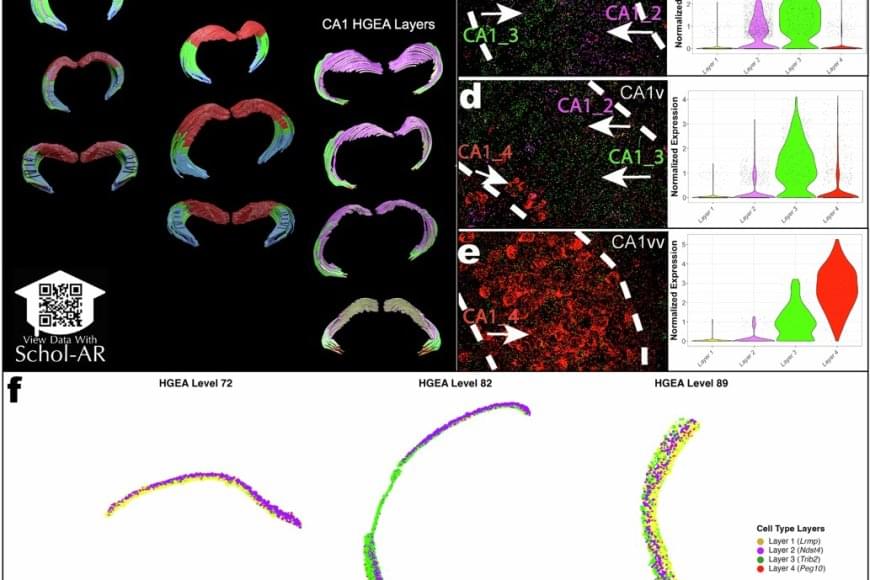

Using a powerful RNA labeling method called RNAscope with high-resolution microscopy imaging, the team captured clear snapshots of single-molecule gene expression to identify CA1 cell types inside mouse brain tissue. Within 58.065 CA1 pyramidal cells, they visualized more than 330,000 RNA molecules—the genetic messages that show when and where genes are turned on. By tracing these activity patterns, the researchers created a detailed map showing the borders between different types of nerve cells across the CA1 region of the hippocampus.

The results showed that the CA1 region consists of four continuous layers of nerve cells, each marked by a distinct set of active genes. In 3D, these layers form sheets that vary slightly in thickness and structure along the length of the hippocampus. This clear, layered pattern helps make sense of earlier studies that saw the region as a more gradual mix or mosaic of cell types.

“When we visualized gene RNA patterns at single-cell resolution, we could see clear stripes, like geological layers in rock, each representing a distinct neuron type,” said a co–first author of the paper. “It’s like lifting a veil on the brain’s internal architecture. These hidden layers may explain differences in how hippocampal circuits support learning and memory.”

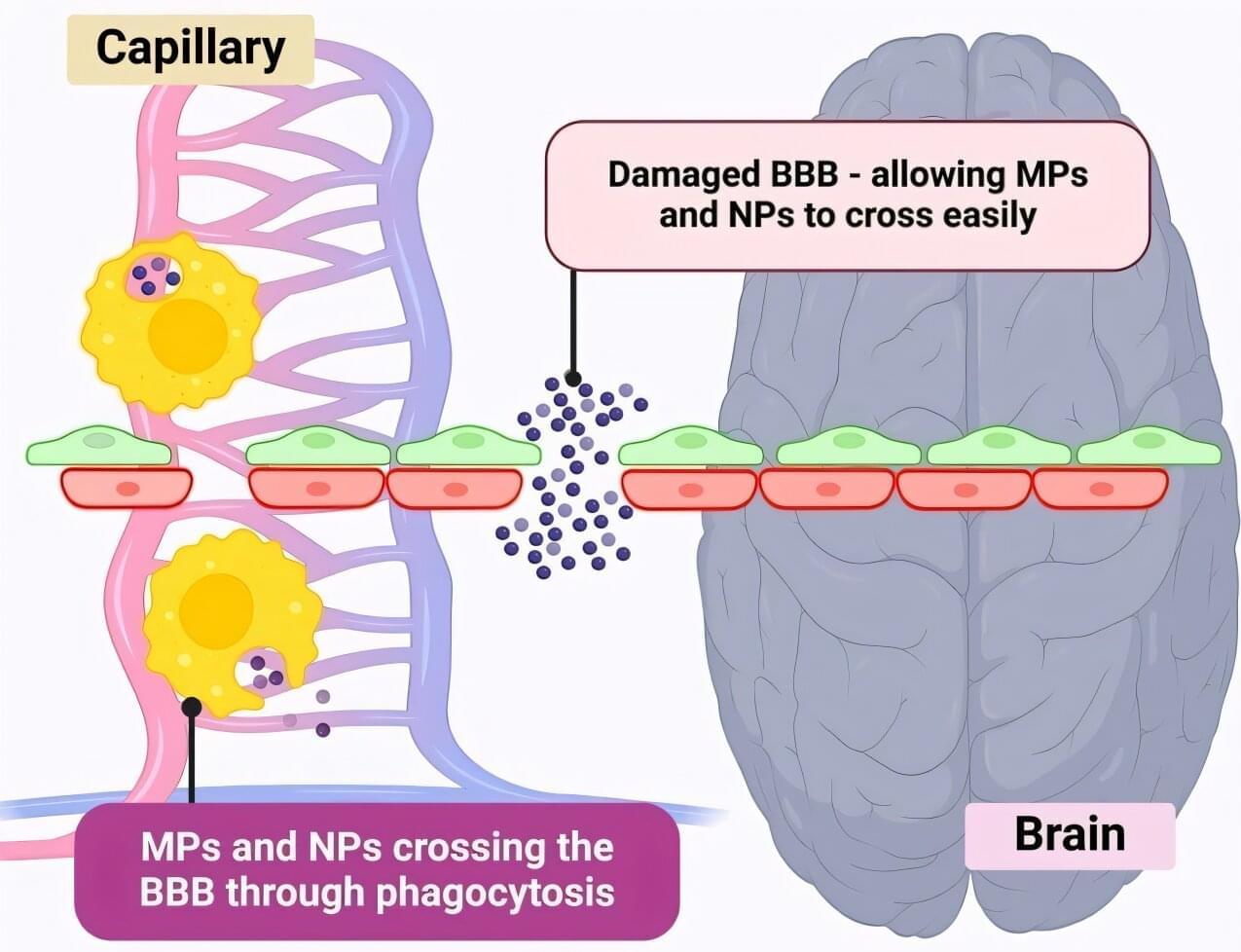

The hippocampus is among the first regions affected in Alzheimer’s disease and is also implicated in epilepsy, depression, and other neurological conditions. By revealing the CA1’s layered structure, the study provides a roadmap to investigate which specific neuron types are most vulnerable in these disorders.

The new CA1 cell-type atlas, built using data from the Hippocampus Gene Expression Atlas (HGEA), is freely available to the global research community. The dataset includes interactive 3D visualizations accessible through the Schol-AR augmented-reality app, which allows scientists to explore hippocampal layers in unprecedented detail.

Researchers have identified a previously unknown pattern of organization in one of the brain’s most important areas for learning and memory. The study, published in Nature Communications, reveals that the CA1 region of a mouse’s hippocampus, a structure vital for memory formation, spatial navigation, and emotions, has four distinct layers of specialized cell types. This discovery changes our understanding of how information is processed in the brain and could explain why certain cells are more vulnerable in diseases like Alzheimer’s and epilepsy.