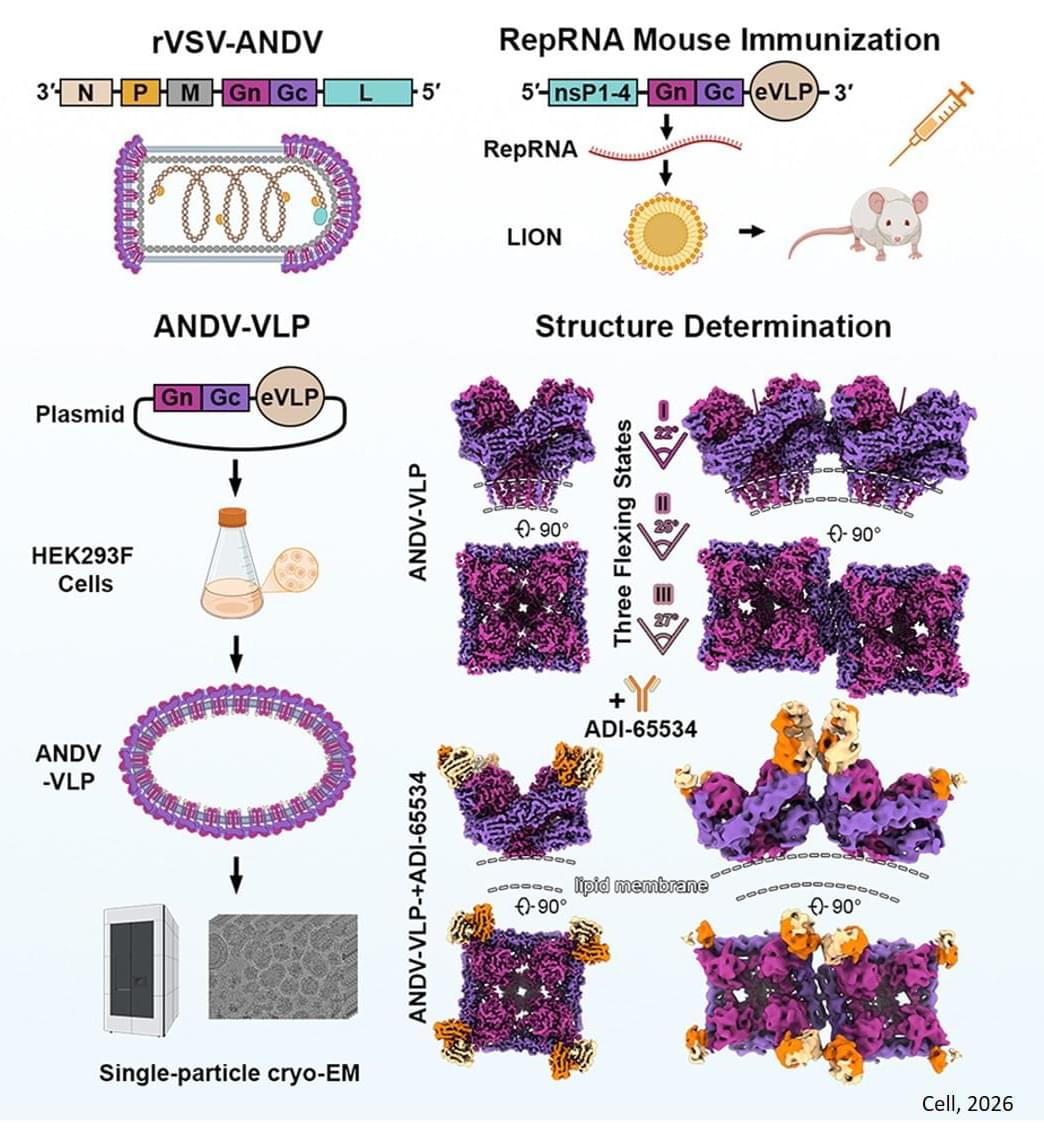

This surface protein complex for the Andes virus is a mushroom-shaped structure called a Gn-Gc tetramer. To map the 3D structures, the team first produced virus-like particles that mimic a real virus, but without the genome that makes a virus infectious. They then used a cryo-electron microscope—which shines an electron beam through a frozen sample and detects the shadows created by molecules—to reconstruct the three-dimensional structures of the Gn-Gc tetramers on the surface of the virus-like particles.

But there was a twist: To obtain extremely high-resolution structures, the researchers painstakingly identified and isolated shadows from only the tetramers that were pointing sidewise relative to the electron beam and ignored those pointing in other directions. This allowed them to borrow a reconstruction method typically used on individual proteins.

The resulting structures have an extremely high resolution of 2.3 angstroms, meaning details the size of just a couple of atoms were effectively captured. That’s enough to represent a transformational improvement over another team’s model of the tetramer from a few years ago, at a resolution of 12 angstroms, still tiny but large enough to produce some key inaccuracies – ones effectively corrected with the newer method and resulting structure.

These latest structures show the Gn-Gc tetramer in a particular state before it has infected a cell. For vaccines or antibody therapies to be most effective against a hantavirus, mimicking surface proteins at this pre-infection stage is essential. ScienceMission sciencenewshighlights.

Hantaviruses, transmitted from rodents to people, have a death rate approaching 40%. They’re found around the world, and because there are no approved vaccines or treatments, they’re among the pathogens of highest concern for future pandemics. They made news in the United States last year when Betsy Arakawa, the wife of actor Gene Hackman, died from a hantavirus infection in New Mexico in March.

New findings published in the journal Cell about the Andes virus, a hantavirus endemic to the southwestern U.S. and other parts of North and South America, represent a crucial first step towards much-needed vaccines and antibody therapies for this and other hantaviruses.