Decades after their experimental realization, wave patterns known as discrete solitons continue to fascinate.

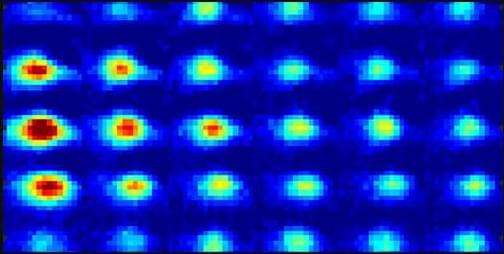

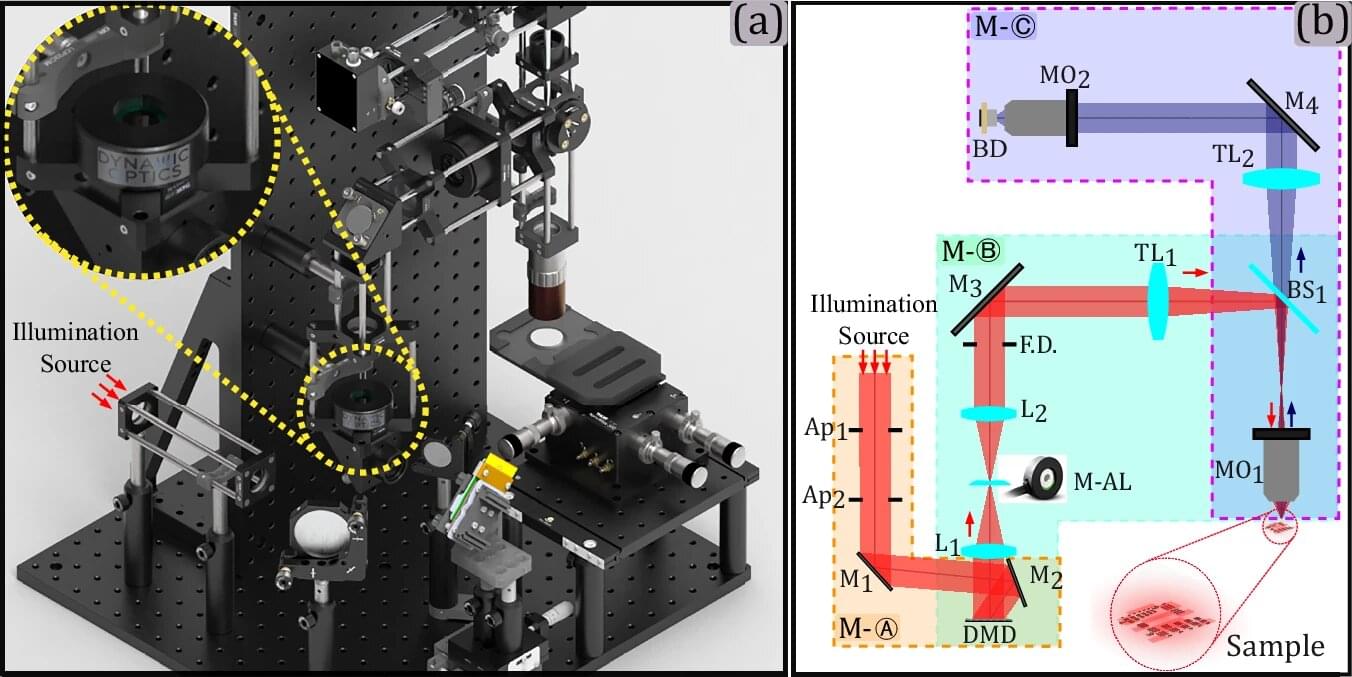

Localized wave patterns in a lattice or other periodic media have been observed using arrays of coupled torsion pendula, chains of Josephson junctions, and arrays of optical waveguides. Joining this diverse repertoire is a recent experiment by Robbie Cruickshank of the University of Strathclyde in the UK and his collaborators [1]. Starting from a Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC) of cesium atoms, the researchers used an ingenious combination of experimental methods to realize, visualize, and theoretically explore coherent wave structures known as discrete solitons. These nonlinear waveforms have long been theorized to exist, and their implications have been extensively studied. In my view, Cruickshank and company’s experiment constitutes the clearest manifestation of discrete solitons so far achieved in ultracold atomic systems, paving the way for a variety of future explorations.

Solitons are localized wave packets that emerge from the interplay of dispersion and nonlinearity. Dispersion tends to make wave packets spread, and nonlinearity tends to localize them. The interplay can be robust and balanced, resulting in long-lived structures. The presence of a lattice introduces a new dimensional unit, the lattice constant, to the interplay, enabling a potential competition between the lattice constant and the scale of the soliton. When the latter is much larger than the former, the soliton is effectively insensitive to the lattice, which it experiences as a continuum. But as the two scales approach one another, lattice effects become more pronounced, and the associated waveforms become discrete solitons. In nonlinear variants of the Schrödinger equation, discreteness typically favors standing waves rather than traveling ones. That’s because the lattice-induced energy barrier known as the Peierls-Nabarro barrier makes discrete solitons less mobile.