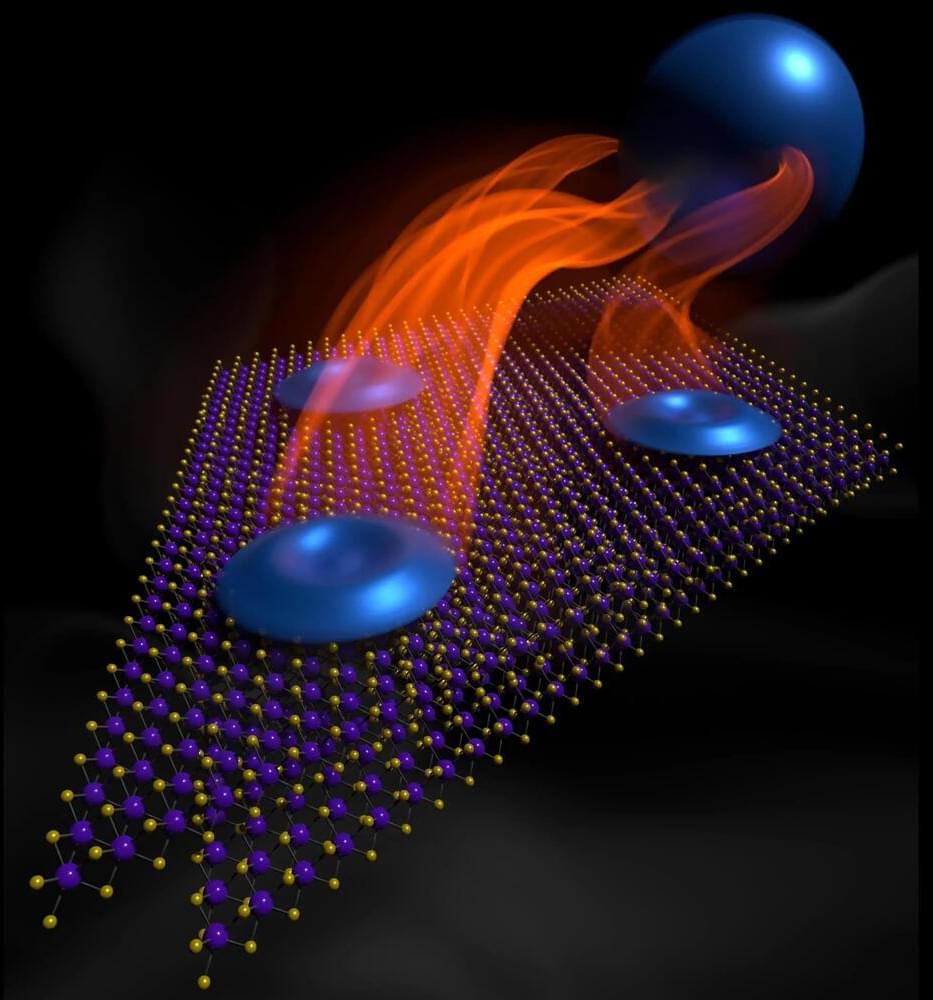

Scientists have made an important step toward developing computers advanced enough to simulate complex natural phenomena at the quantum level. While these types of simulations are too cumbersome or outright impossible for classical computers to handle, photonics-based quantum computing systems could provide a solution.

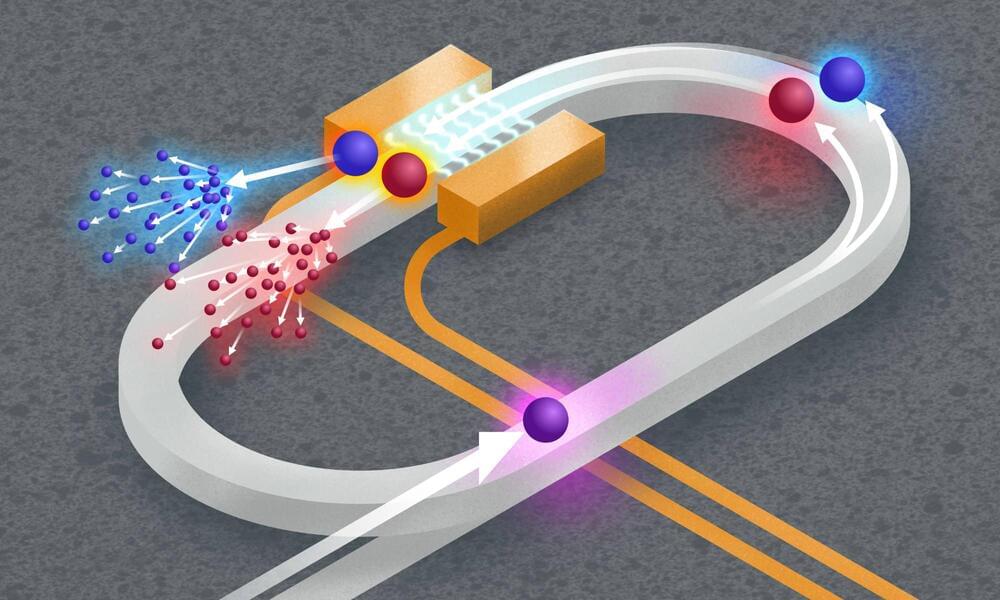

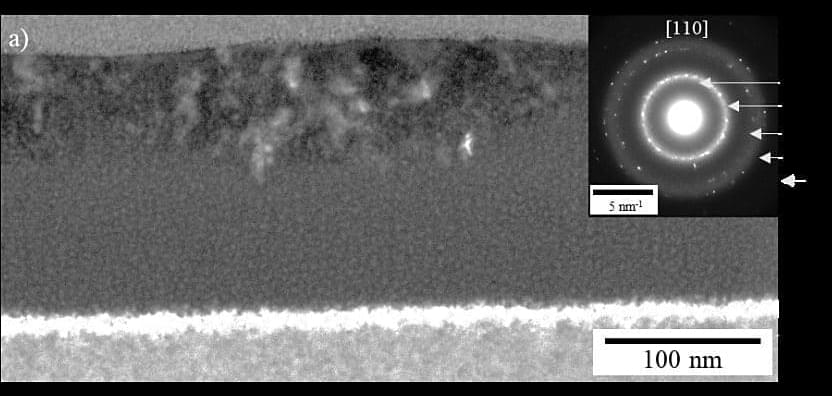

A team of researchers from the University of Rochester’s Hajim School of Engineering & Applied Sciences developed a new chip-scale optical quantum simulation system that could help make such a system feasible. The team, led by Qiang Lin, a professor of electrical and computer engineering and optics, published their findings in Nature Photonics.

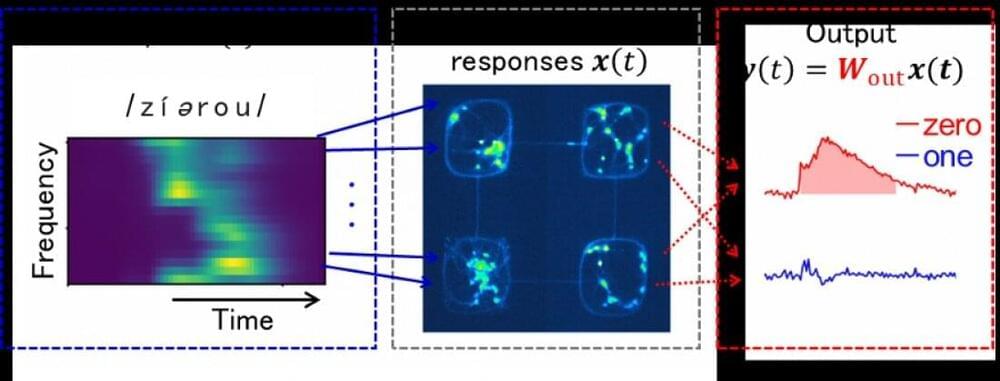

Lin’s team ran the simulations in a synthetic space that mimics the physical world by controlling the frequency, or color, of quantum entangled photons as time elapses. This approach differs from the traditional photonics-based computing methods in which the paths of photons are controlled, and also drastically reduces the physical footprint and resource requirements.