Another tech giant is coming to the suburbs.

In the next section, we’ll look at the ways scientists can grow nanowires from the bottom up.

Looking at the Nanoscale.

A nanoscientist’s microscope isn’t the same kind that you’ll find in a high school chemistry lab. When you get down to the atomic scale, you’re dealing with sizes that are actually smaller than the wavelength of visible light. Instead, a nanoscientist could use a scanning tunneling microscope or an atomic force microscope. Scanning tunneling microscopes use a weak electric current to probe the scanned material. Atomic force microscopes scan surfaces with an incredibly fine tip. Both microscopes send data to a computer, which assembles the information and projects it graphically onto a monitor.

Developing an advanced Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) is only the beginning.

“In order to prove a theory of consciousness is right, you have to see it for yourself,” Hodak explains. “That will require these big brain-computer interfaces.”

Hodak thinks that once humans understand how billions of neurons bind together to create a unified experience — what neuroscientists call “the binding problem” — we can start doing truly wild things.

I almost hesitate to say some of those wild things include multiple brains working to form one consciousness. “You could really, in a very fundamental sense, talk about redrawing the border around a brain, possibly to include four hemispheres, or a device, or a whole group of people,” he says.

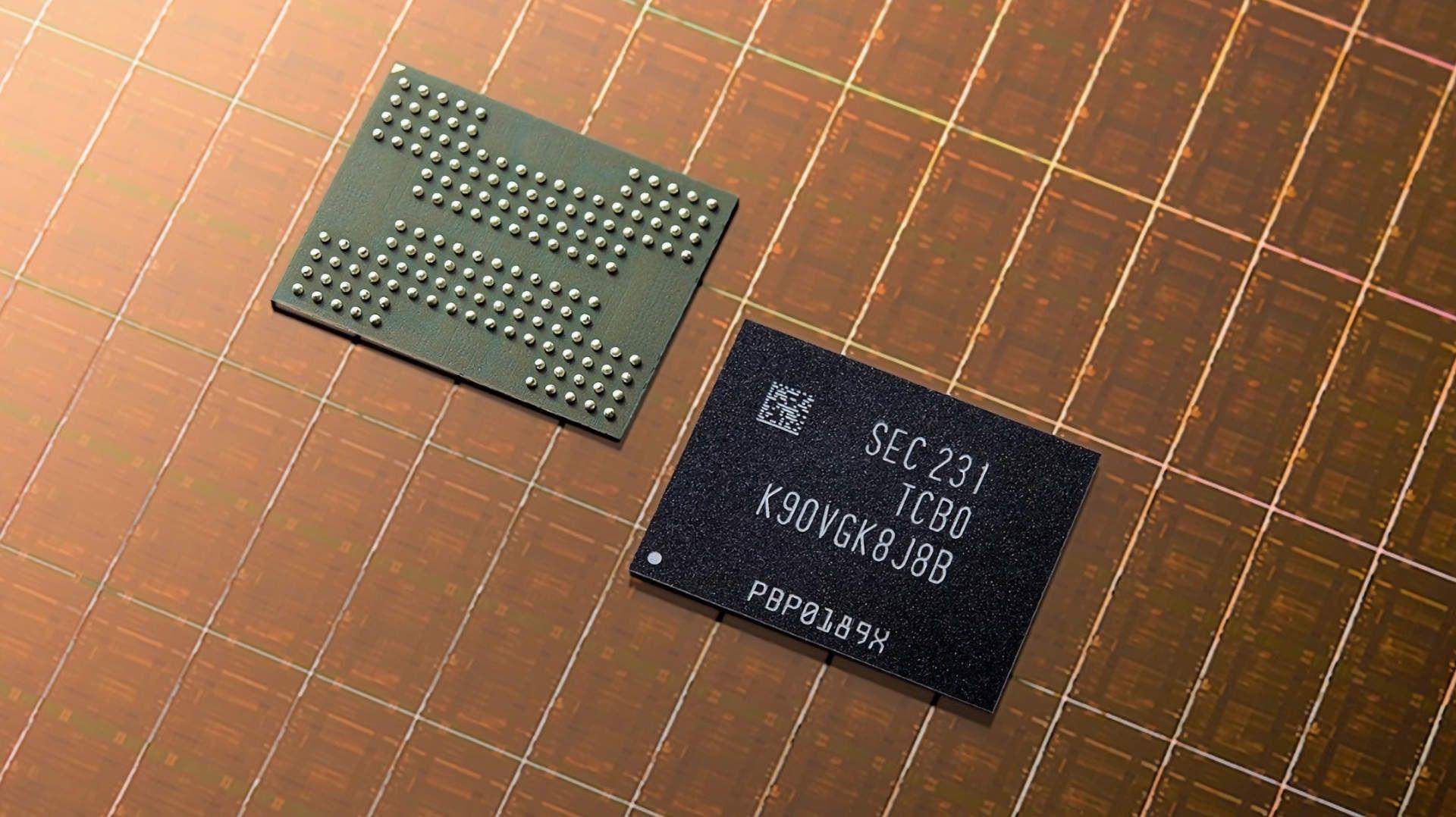

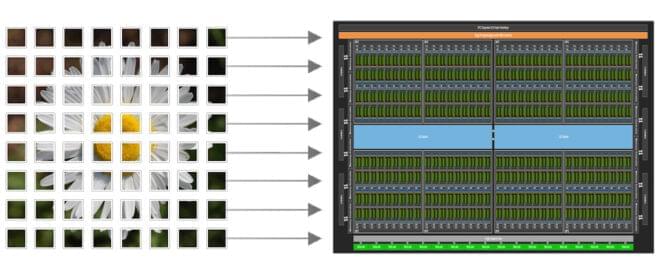

With its largest advancement since the NVIDIA CUDA platform was invented in 2006, CUDA 13.1 is launching NVIDIA CUDA Tile. This exciting innovation introduces a virtual instruction set for tile-based parallel programming, focusing on the ability to write algorithms at a higher level and abstract away the details of specialized hardware, such as tensor cores.

CUDA exposes a single-instruction, multiple-thread (SIMT) hardware and programming model for developers. This requires (and enables) you to exhibit fine-grained control over how your code is executed with maximum flexibility and specificity. However, it can also require considerable effort to write code that performs well, especially across multiple GPU architectures.

There are many libraries to help developers extract performance, such as NVIDIA CUDA-X and NVIDIA CUTLASS. CUDA Tile introduces a new way to program GPUs at a higher level than SIMT.

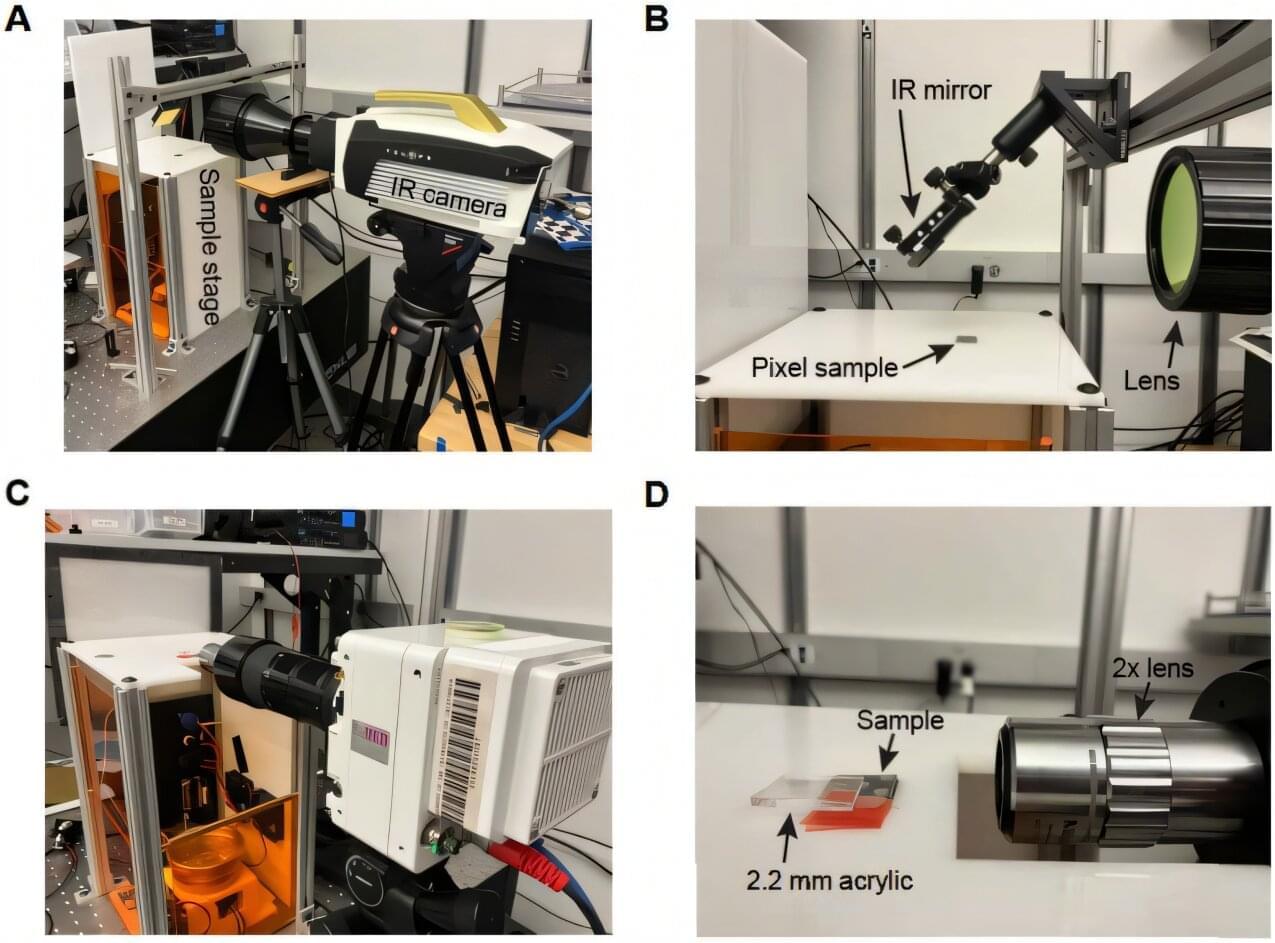

Researchers at UC Santa Barbara have invented a display technology for on-screen graphics that are both visible and haptic, meaning that they can be felt via touch.

The screens are patterned with tiny pixels that expand outward, yielding bumps when illuminated, enabling the display of dynamic graphical animations that can be seen with the eyes and felt with the hand. This technology could one day enable high-definition visual-haptic touch screens for automobiles, mobile computing or intelligent architectural walls.

Max Linnander, a Ph.D. candidate in the RE Touch Lab of mechanical engineering professor Yon Visell, led the research, which appears in the journal Science Robotics.

Trapped neutral atoms are an attractive platform for quantum computing, as large arrays of atomic qubits can be arranged and manipulated to perform gate operations. However, the loss of useable atoms—either from escape or from disturbance—can be a limitation for long computations with repeated measurements. Researchers at Atom Computing, a company in California, have devised a “reset or reload” protocol that mitigates atom losses [1]. The method was successfully employed during a computation consisting of 41 cycles of qubit measurements.

All current quantum computers require error correction, which involves measuring certain qubits at intermediate steps of a computation. Reusing these qubits would avoid needing a prohibitively high overhead in qubit numbers, says team member Matthew Norcia. But in the case of atoms, the process of resetting measured qubits risks disturbing unmeasured ones.

To overcome this challenge, the researchers have developed a way to shield unmeasured atoms from the resetting process. They use targeted laser beams to immunize the unmeasured atoms against excitation by shifting their resonances. They then turn on a second set of lasers that cool the measured atoms and reinitialize them, enabling them to join the unmeasured atoms in the next computational step.