A group of 60 scientists called for a moratorium on solar geoengineering last month, including technologies such as stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI). This involves a fleet of aeroplanes releasing aerosol particles – which reflect sunlight back to outer space – into the atmosphere, cooling down the Earth.

SAI might make the sky slightly whiter. But this is the least of our concerns. SAI could pose grave dangers, potentially worse than the warming it seeks to remedy. To understand the risks, we’ve undertaken a risk assessment of this controversial technology.

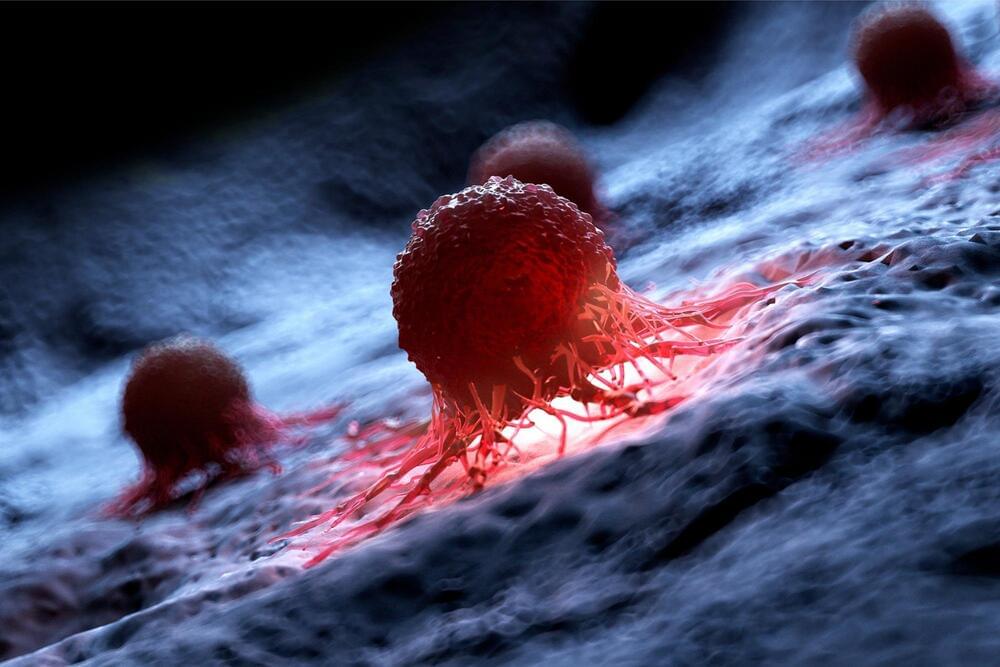

A cooler Earth means less water would be evaporating from its surfaces into the atmosphere, changing rainfall patterns. This could produce ripple effects across the world’s ecosystems – but the exact nature of these effects depends on how SAI is used. Poor coordination of aerosol release could lead to extreme rainfall in some places and blistering drought in others, further triggering the spread of diseases.