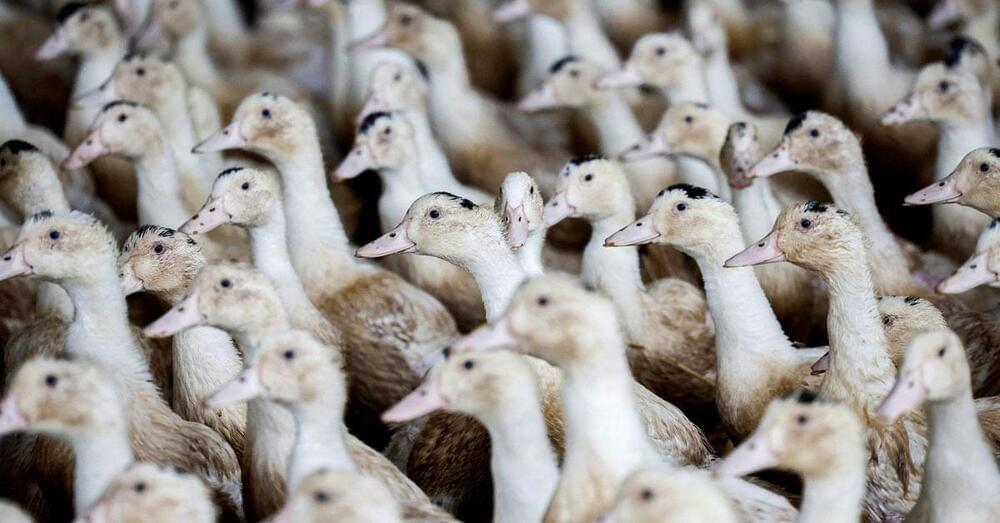

PARIS, Dec 5 (Reuters) — France raised the risk level of bird flu to ‘high’ from ‘moderate’ on Tuesday after new cases of the disease were detected, forcing poultry farms to keep birds indoors to stem the spread of the highly contagious virus.

The decision by the agriculture ministry was published in the Official Journal on Tuesday.

Avian influenza, commonly known as bird flu, has led to the culling of hundreds of millions birds worldwide in recent years.