Enter Fabian Voigt, a molecular biologist at Harvard University and inventor of the new design. He was reading a book about animal vision when he encountered the odd case of scallops’ eyes. Unlike most animals, whose eyes feature retinas that send images to the brain, scallops have mantles covered with hundreds of tiny blue dots, each of which contains a curved mirror at its back. As light passes through each eye’s lens, its inner mirror reflects the light back onto the creature’s photoreceptors to create an image that then allows the scallop to respond to its environment.

An amateur astronomer since he was a teenager, Voigt realized the scallop’s eye design resembled a kind of telescope invented nearly 100 years ago called the Schmidt telescope. The Kepler Space Telescope, which orbits Earth, uses a similar curved mirror design to magnify far-away light from exoplanets. Voigt realized that by shrinking the mirror, using lasers for light, and filling the space between the mirror and the detector with liquid to minimize light scattering, the design could be adapted to fit inside a microscope.

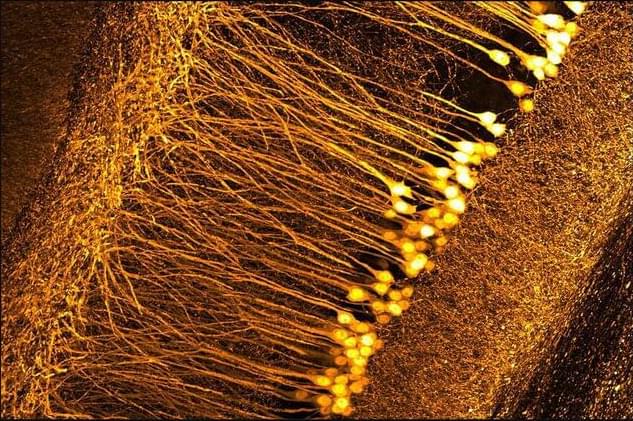

So, Voigt and colleagues built a prototype based on those specs. Light enters from the top, passes through a curved plate that corrects for the mirror’s curvature, then bounces off a mirror to hit a sample and magnify it. The curved mirror can magnify the image much like a lens, Voigt says. It allows researchers to look at samples suspended in any kind of liquid, simplifying the process. Voigt says the design could be particularly useful for researchers who study organs or even entire organisms, such as mice or embryos, that have been made completely transparent by artificially removing their pigment.