Finally, portable thermal imaging devices could be here soon.

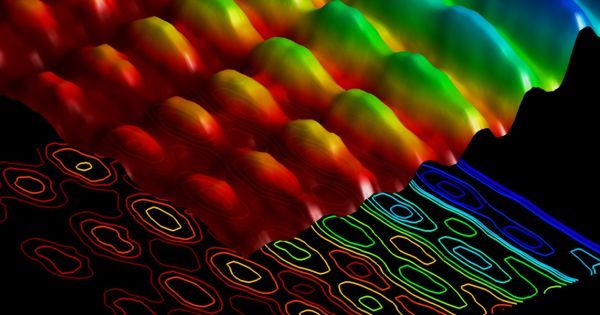

The primary source of infrared radiation is heat—the radiation produced by the thermal motion of charged particles in matter, including the motion of the atoms and molecules in an object. The higher the temperature of an object, the more its atoms and molecules vibrate, rotate, twist through their vibrational modes, the more infrared radiation they radiate. Because infrared detectors can be “blinded” by their own heat, high-quality infrared sensing and imaging devices are usually cooled down, sometimes to just a few degrees above absolute zero. Though they are very sensitive, the hardware required for cooling renders these instruments less-than-mobile, energy-inefficient and limits in-the-field applications.

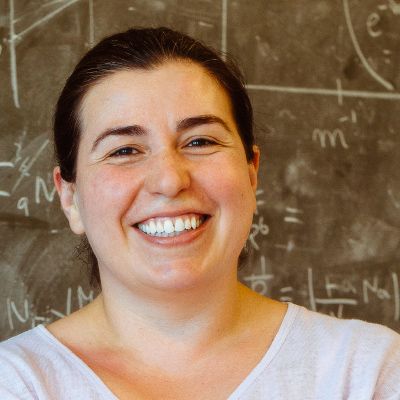

A paper published this week in the journal Optics Express, from The Optical Society (OSA), describes a new type of portable, field-friendly, mid-infrared detector that operates at room temperature. Room-temperature operation, notes Andreas Harrer of the TU-Wien Center for Micro- and Nanostructures, Austria and the first author of the paper, “is essential for detectors to be energy-efficient enough for portable and handheld applications. We want to pave the way to an infrared-detection technology which is flexible in design and meets all requirements for compact integrated field-applicable detection systems.”

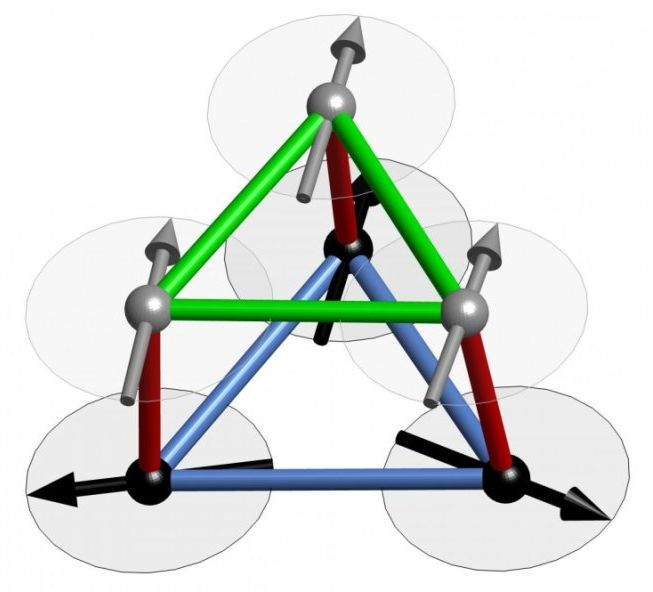

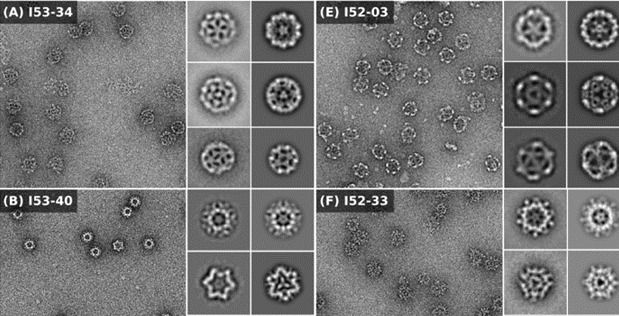

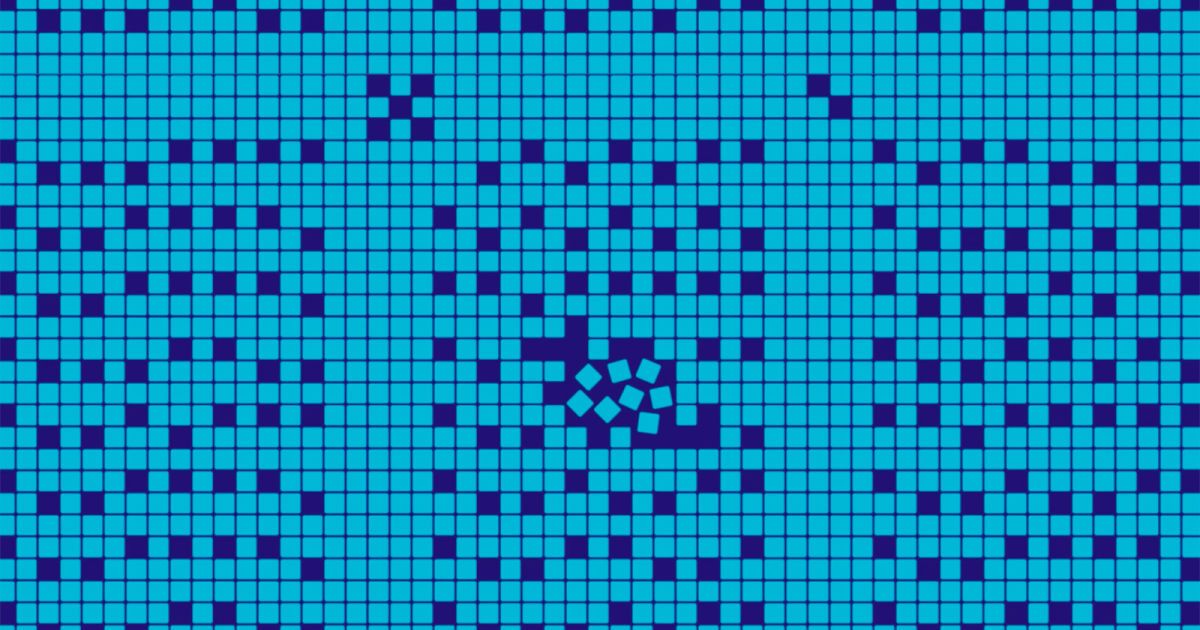

The type of instrument developed by Harrer and his colleagues is known as a quantum cascade detector, or QCD. A QCD is a high-speed detector composed of semiconductor devices that sense specific wavelengths of infrared light and convert that light into proportionate electrical signals. A unique aspect of the design described by Harrer and his colleagues is that it consists of an 8 × 8 array of pixels, each approximately 110 microns square. Tuning is achieved by specifically adjusting the well and the barrier dimensions to a wavelength of 4.3 microns.