It’s now easier for scientists to create gene-edited insects thanks to a new technique called “direct parental CRISPR.”

Category: genetics – Page 120

Join us on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/MichaelLustgartenPhD

Discount Links:

NAD+ Quantification: https://www.jinfiniti.com/intracellular-nad-test/

Use Code: ConquerAging At Checkout.

Epigenetic Testing: https://trudiagnostic.com/?irclickid=U-s3Ii2r7xyIU-LSYLyQdQ6…M0&irgwc=1

Use Code: CONQUERAGING

At-Home Metabolomics: https://www.iollo.com?ref=michael-lustgarten.

Mayo Clinic scientists are building an expansive library of DNA blueprints of disease-causing bacterial species. The unique collection of genomic sequences is serving as a reference database to help doctors provide rapid and precise diagnoses and pinpoint targeted treatments to potentially improve patient outcomes.

The vast data set is also being studied by researchers in an effort to develop new individualized treatments to combat bacteria-related diseases.

Bacterial infections were linked to more than 7 million global deaths in 2019. Of those, nearly 1.3 million were the direct result of drug-resistant bacteria, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Dopamine is a type of neurotransmitter that can provide an intense feeling of reward. It has been a long-standing assumption that most, if not all, dopamine neurons solely respond to rewards or reward-predicting cues. However, a study in mice led by researchers at Northwestern University reveals dopamine may also control movements. The researchers uncovered that one genetic subtype fires when the body moves and that these neurons do not respond to rewards at all.

The findings are published in Nature Neuroscience in an article titled, “Unique functional responses differentially map onto genetic subtypes of dopamine neurons,” and shed new light on the brain which may lead to new research on Parkinson’s disease, which is characterized by the loss of dopamine neurons yet affects the motor system.

“Dopamine neurons are characterized by their response to unexpected rewards, but they also fire during movement and aversive stimuli,” the researchers wrote. “Dopamine neuron diversity has been observed based on molecular expression profiles; however, whether different functions map onto such genetic subtypes remains unclear. In this study, we established that three genetic dopamine subtypes within the substantia nigra pars compacta, characterized by the expression of Slc17a6 (Vglut2), Calb1, and Anxa1, each have a unique set of responses to rewards, aversive stimuli, and accelerations and decelerations, and these signaling patterns are highly correlated between somas and axons within subtypes.”

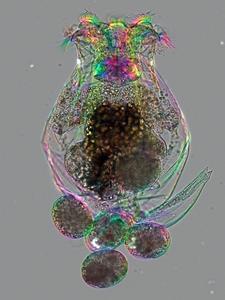

Rotifers are excellent research organisms for studying the biology of aging, DNA repair mechanisms, and other fundamental questions. Now, using an innovative application of CRISPrCas9, scientists at the Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, have devised a method for making precise, heritable changes to the rotifer genome, enabling the larger community of scientists to deploy the rotifer as a genetically tractable lab organism.

It’s one of the mysteries of nature: How does the axolotl, a small salamander, boast a superhero-like ability to regrow nearly any part of its body? For years, scientists have studied the amazing regenerative properties of the axolotl to inform wound healing in humans.

Now, Stanford Medicine researchers have made a leap forward in understanding what sets the axolotl apart from other animals. Axolotls, they discovered, have an ultra-sensitive version of mTOR, a molecule that acts as an on-off switch for protein production. And, like survivalists who fill their basements with non-perishable food for hard times, axolotl cells stockpile messenger RNA molecules, which contain genetic instructions for producing proteins. The combination of an easily activated mTOR molecule and a repository of ready-to-use mRNAs means that after an injury, axolotl cells can quickly produce the proteins needed for tissue regeneration.

The new findings were published July 26 in Nature.

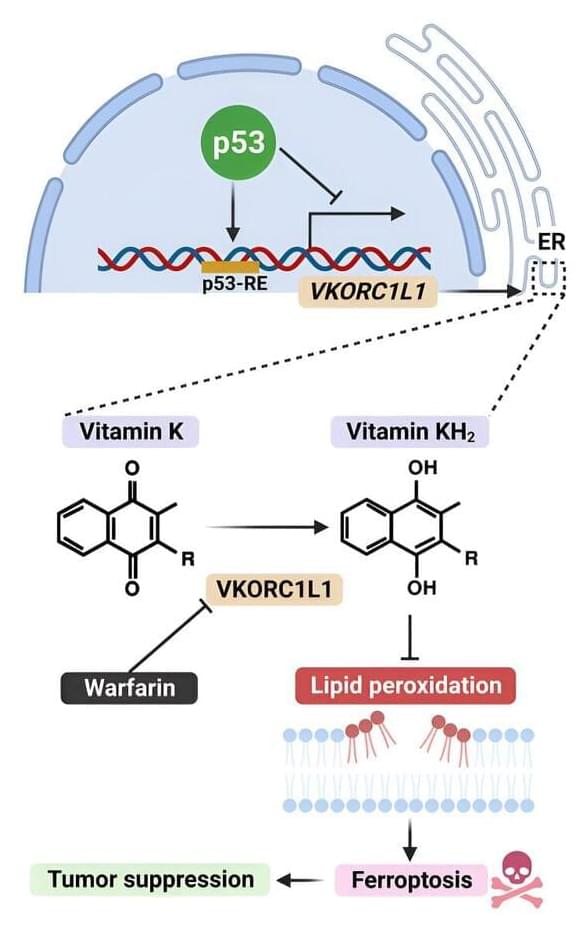

Warfarin, a widely used blood thinner, appears to have potent anti-cancer properties, according to a study by Columbia University researchers. The study, conducted in human cells and in mice, found that warfarin stops tumors from interfering with a self-destruct mechanism that cells initiate when they detect mutations or other abnormalities.

“Our findings suggest that warfarin, which is already approved by the FDA, could be repurposed to treat a variety of cancers, including pancreatic cancer,” says study leader Wei Gu, Ph.D., the Abraham and Mildred Goldstein Professor of Pathology & Cell Biology (in the Institute for Cancer Genetics) at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons.

The study is titled “Regulation of VKORC1L1 is critical for p53-mediated tumor suppression through vitamin K metabolism,” and it was published July 18 in Cell Metabolism. Postdoctoral researcher scientists Xin Yang, Ph.D., and Zhe Wang, Ph.D., contributed equally as first authors.

An interdisciplinary team of mathematicians, engineers, physicists, and medical scientists has discovered a surprising connection between pure mathematics and genetics. This connection sheds light on the structure of neutral mutations and the evolution of organisms.

Number theory, the study of the properties of positive integers, is perhaps the purest form of mathematics. At first sight, it may seem far too abstract to apply to the natural world. In fact, the influential American number theorist Leonard Dickson wrote “Thank God that number theory is unsullied by any application.”

And yet, again and again, number theory finds unexpected applications in science and engineering, from leaf angles that (almost) universally follow the Fibonacci sequence, to modern encryption techniques based on factoring prime numbers. Now, researchers have demonstrated an unexpected link between number theory and evolutionary genetics.

Each cell in the body stores its genetic information in DNA in a stable and protected form that is readily accessible for the cell to carry on its activities. Nevertheless, mutations—changes in genetic information—occur throughout the human genome and can have a powerful influence on human health and evolution.

“Our team is interested in a classical question about mutation—why do mutation rates in the genome vary so tremendously from one DNA location to another? We just do not have a clear understanding of why this occurs,” said Dr. Md. Abul Hassan Samee, assistant professor of integrative physiology at Baylor College of Medicine and corresponding author of the work.

Previous studies have shown that the DNA sequences flanking a mutated position—the sequence context—play a strong role in the mutation rate. “But this explanation still leaves unanswered questions,” Samee said. “For example, one type of mutation occurs frequently in a specific sequence context while a different type of mutation occurs infrequently in that same sequence context. So, we think that a different mechanism could explain how mutation rates vary in the genome. We know that each building block or base that makes up a DNA sequence has its own 3D chemical shape. We proposed, therefore, that there is a connection between DNA shape and mutations rates, and this paper shows that our idea was correct.”

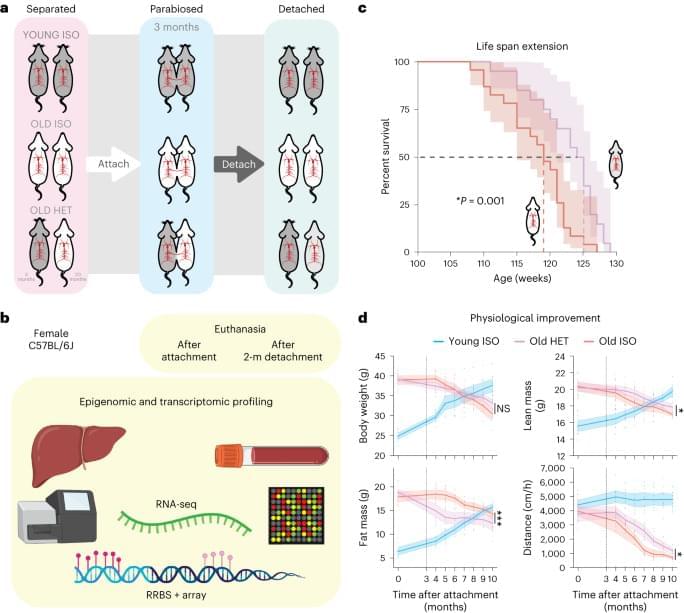

Heterochronic parabiosis ameliorates age-related diseases in mice, but how it affects epigenetic aging and long-term health was not known. Here, the authors show that in mice exposure to young circulation leads to reduced epigenetic aging, an effect that persists for several months after removing the youthful circulation.