Apr 2, 2020

Ten Weeks to Crush the Curve

Posted by Nicholi Avery in categories: biotech/medical, economics, sustainability

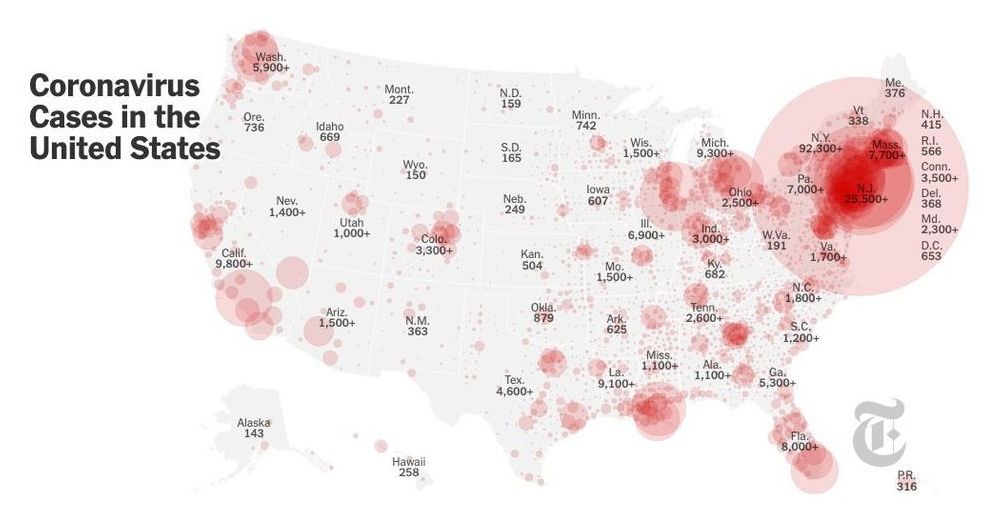

The President says we are at war with the coronavirus. It’s a war we should fight to win.

The economy is in the tank, and anywhere from thousands to more than a million American lives are in jeopardy. Most analyses of options and trade-offs assume that both the pandemic and the economic setback must play out over a period of many months for the pandemic and even longer for economic recovery. However, as the economists would say, there is a dominant option, one that simultaneously limits fatalities and gets the economy cranking again in a sustainable way.

That choice begins with a forceful, focused campaign to eradicate Covid-19 in the United States. The aim is not to flatten the curve; the goal is to crush the curve. China did this in Wuhan. We can do it across this country in 10 weeks.