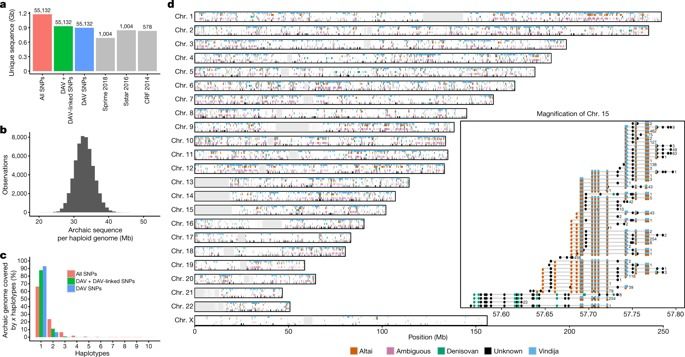

Human evolutionary history is rich with the interbreeding of divergent populations. Most humans outside of Africa trace about 2% of their genomes to admixture from Neanderthals, which occurred 50–60 thousand years ago1. Here we examine the effect of this event using 14.4 million putative archaic chromosome fragments that were detected in fully phased whole-genome sequences from 27,566 Icelanders, corresponding to a range of 56,388–112,709 unique archaic fragments that cover 38.0–48.2% of the callable genome. On the basis of the similarity with known archaic genomes, we assign 84.5% of fragments to an Altai or Vindija Neanderthal origin and 3.3% to Denisovan origin; 12.2% of fragments are of unknown origin. We find that Icelanders have more Denisovan-like fragments than expected through incomplete lineage sorting. This is best explained by Denisovan gene flow, either into ancestors of the introgressing Neanderthals or directly into humans. A within-individual, paired comparison of archaic fragments with syntenic non-archaic fragments revealed that, although the overall rate of mutation was similar in humans and Neanderthals during the 500 thousand years that their lineages were separate, there were differences in the relative frequencies of mutation types—perhaps due to different generation intervals for males and females. Finally, we assessed 271 phenotypes, report 5 associations driven by variants in archaic fragments and show that the majority of previously reported associations are better explained by non-archaic variants.

Menu

-

Sitemap

- Cool places

- Ark I

- Blue Beauty

- EM Launch

- GETAS

- Official Song

- Home

- About

- Blog

- Programs

- Reports

- A-PRIZE

- Donate

- Join Us

- Newsletter

- Quotes

- Store

- Press Releases

Tag cloud

aging AI Alzheimer's anti-aging Artificial Intelligence bioquantine bioquark biotech biotechnology bitcoin blockchain brain death cancer cryptocurrency culture Death existential risks extinction future futurism Google health healthspan humanity ideaxme immortality Interstellar Travel ira pastor Life extension lifespan longevity NASA Neuroscience politics reanima regenerage regeneration research risks singularity space sustainability technology transhumanism wellnessCategories

- 3D printing

- 4D printing

- Peter Diamandis

- DNA

- Ray Kurzweil

- Elon Musk

- Singularity University

- Skynet

- Mark Zuckerberg

- aging

- alien life

- anti-gravity

- architecture

- asteroid/comet impacts

- astronomy

- augmented reality

- automation

- bees

- big data

- bioengineering

- biological

- bionic

- bioprinting

- biotech/medical

- bitcoin

- blockchains

- business

- chemistry

- climatology

- complex systems

- computing

- cosmology

- counterterrorism

- cryonics

- cryptocurrencies

- cybercrime/malcode

- cyborgs

- defense

- disruptive technology

- driverless cars

- drones

- economics

- education

- electronics

- employment

- encryption

- energy

- engineering

- entertainment

- environmental

- ethics

- events

- evolution

- existential risks

- exoskeleton

- finance

- first contact

- food

- fun

- futurism

- general relativity

- genetics

- geoengineering

- geography

- geology

- geopolitics

- governance

- government

- gravity

- habitats

- hacking

- hardware

- health

- holograms

- homo sapiens

- human trajectories

- humor

- information science

- innovation

- internet

- journalism

- law

- law enforcement

- lifeboat

- life extension

- machine learning

- mapping

- materials

- mathematics

- media & arts

- military

- mobile phones

- moore's law

- nanotechnology

- neuroscience

- nuclear energy

- nuclear weapons

- open access

- open source

- particle physics

- philosophy

- physics

- policy

- polls

- posthumanism

- privacy

- quantum physics

- rants

- robotics/AI

- satellites

- science

- scientific freedom

- security

- sex

- singularity

- software

- solar power

- space

- space travel

- strategy

- supercomputing

- surveillance

- sustainability

- telepathy

- terrorism

- theory

- thought controlled

- time travel

- tractor beam

- transhumanism

- transparency

- transportation

- treaties

- virtual reality

- water

- weapons

- wearables

Top 30 Authors

- Genevieve Klien

- Quinn Sena

- Dan Breeden

- Shubham Ghosh Roy

- Saúl Morales Rodriguéz

- Shailesh Prasad

- Gemechu Taye

- Kelvin Dafiaghor

- Paul Battista

- Karen Hurst

- Dan Kummer

- Klaus Baldauf

- Jose Ruben Rodriguez Fuentes

- Omuterema Akhahenda

- Derick Lee

- Alberto Lao

- Shane Hinshaw

- Raphael Ramos

- Sean Brazell

- Steve Hill

- Seb

- Cecile G. Tamura

- Michael Lance

- Brent Ellman

- Jason Blain

- Atanas Atanasov

- Montie Adkins

- Andreas Matt

- Ira S. Pastor

- Nicholi Avery

All Authors

- 21st Century Tech Blog

- Maria Entraigues Abramson

- Mario Acosta

- Montie Adkins

- Andres Agostini

- Yugal Agrawal

- Tanvir Ahmed

- Omuterema Akhahenda

- Kemal Akman

- Liliana Alfair

- Greg Allison

- Jacob Anderson

- Lon Anderson

- Athena Andreadis

- Amara Angelica

- Michael Anissimov

- Elmar Arunov

- Dustin Ashley

- Atanas Atanasov

- Tracy R. Atkins

- Adriano Autino

- Nicholi Avery

- Yasemin B.

- Nicola Bagalà

- Gerard Bain

- Lawrence Baines

- Buddy Baker

- Klaus Baldauf

- Ankur Bargotra

- Joseph Barney

- Florence Pauline Gardose Basubas

- Jason Batt

- Jeremy Dylan Batterson

- Paul Battista

- Eric Baum

- Zola Balazs Bekasi

- Danny Belkin

- Joe Bennett

- Harry J. Bentham

- Daniel Berleant

- James Bickerton

- Alexandria Black

- Chuck Black

- Jason Blain

- Scott Bleackley

- Heather Blevins

- Phillipe Bojorquez

- Robert Bosnjak

- Johnny Boston

- Phil Bowermaster

- Sean Brazell

- Dan Breeden

- Julia Brodsky

- Chuck Brooks

- Arthur Brown

- Jim Brownfield

- Chris Browning

- Dirk Bruere

- Rachel Burger

- Bruce Burke

- Matthew Calero

- Ryan Calo

- Randy Campbell

- Alexandra Carmichael

- Alan Carsey

- Alessandro Carvalho

- Jamais Cascio

- John Cassel

- Peter Cawdron

- Juliian C'estMoi

- Rob Chamberlain

- Dennis Chamberland

- Natalie Chan

- Dmitrii Chekh

- Nicolas Chernavsky

- Chiara Chiesa

- Gary Michael Church

- Darnell Clayton

- Sidney Clouston

- Seth Cochran

- Logan Thrasher Collins

- José Cordeiro

- Nick Cordingly

- Franco Cortese

- Rebecca D. Costa

- Wei Cui

- Steven Curley

- Keith Curtis

- Sean Cusack

- Schwann Cybershaman

- Kelvin Dafiaghor

- Jayaprakash Damothran

- Dalton Daniel

- Richard Darienzo

- DataPacRat

- Jim Davidson

- John Davies

- Scott Davis

- Tahir Dawood

- Stan Daymond

- Alex Deadpool

- Yuri Deigin

- Peter DeKraker

- Alan DeRossett

- Ovie Desire

- Clyde DeSouza

- Leif DeVaney

- Michael Dickey

- Odette Bohr Dienel

- Lucas Dimoveo

- Mike Diverde

- Michael Dodd

- James Doehring

- Johnathan Doetry

- Bruce Dorminey

- James Dunn

- Ratnesh Dwivedi

- Bill D'Zio

- Dean Eaketts

- Amnon H. Eden

- Odd Edges

- Alexandros El

- Brent Ellman

- Dr Nick Engerer

- Joaquín Alvira Enríquez

- Blair Erickson

- Marcos Than Esponda

- Chris Evans

- Dylan Evans

- Woody Evans

- Eamon Everall

- Dan Faggella

- Alvaro Fernandez

- Christopher Field

- Adam Ford

- Durwin Foster

- Will Fox

- Bob Freeman

- Ron Friedman

- Magnus Frolov

- Jose Ruben Rodriguez Fuentes

- Steve Fuller

- Matt Funk

- Muhammad Furqan

- Future Timeline

- Edward Futurem

- Hiel Salming Gagarin

- Ole Peter Galaasen

- Colin Gallagher

- John Gallagher

- Julius Garcia

- Bryan Gatton

- Victoria Generao

- Joseph Anoop George

- Jennifer Gidley

- Paul Gonçalves

- Markus Goritschnig

- Ron Gowans-Savage

- Lily Graca

- Richard Graf

- Andrés Grases

- M. A. Greenstein

- Michael Greve

- Robert Grüning

- William E. Halal

- Ian Hale

- Chris K. Haley

- Tristan Hambling

- Stuart Hameroff

- James Hampton

- Jacob Haqq-Misra

- Narenda Har

- Stevan Harnad

- Matthew Harris

- Steven B. Harris

- Brady Hartman

- Mishari Al Hasawi

- Maciamo Hay

- Ciaran Healy

- Lola Heavey

- Andreas M. Hein

- Orenda Urbano Hernández

- Denise Herzing

- Martin Higgins

- Steve Hill

- Shane Hinshaw

- Karlyn Hixson

- Cherrie Ho

- Jeffrey Dean Hochderffer

- Dave Holt

- Matthew Holt

- David Houlding

- Kevin Huang

- Neurozo Huang

- John Hunt

- Nancie Hunter

- Eric Hunting

- Karen Hurst

- Krys Hyff

- Kelly Idehen

- Brett Gallie II

- Early Boykins III

- Robin Indeededo

- Peer Infinity

- Initiative for Interstellar Studies

- Zoltan Istvan

- Ruth Itzhaki

- Joseph Jackson

- Arav Jain

- Mary Jain

- Naveen Jain

- Vivek Jaiswal

- Chris Parbey Jnr

- Joseph John

- Summer Johnson

- Matt Johnstone

- Faith Jones

- Roderick Jones

- Steve Jordan

- Henrique Jorge

- Alan Jurisson

- Roman Kam

- Richard Kane

- Al Karaki

- Håkon Skaarud Karlsen

- Stu Kauffman

- James Felton Keith

- David J. Kelley

- Bill Kemp

- Chris J. Kent

- Samuel H. Kenyon

- Tom Kerwick

- Nare Khachatryan

- Farooq Khan

- Lawrence Klaes

- Bruce Klein

- Eric Klien

- Genevieve Klien

- Josef Koch

- Randal A. Koene

- Maria Konovalenko

- Oguzhan Kosar

- William Kraemer

- LHC Kritik

- Bob Krone

- Paulus Kudyak

- Dan Kummer

- Ray Kurzweil

- Marios Kyriazis

- Ósìnàkáchì Ákùmà Kálù

- Michael Lance

- Alberto Lao

- Mark Larkento

- Brandon Larson

- Cadell Last

- Michael LaTorra

- Manuel Canovas Lechuga

- Derick Lee

- Jeffrey L. Lee

- Michael Lee

- Valentina Lencautan

- Lilia Lens-Pechakova

- Gerd Leonhard

- Denisa Lepădatu

- Amberley Levine

- Jeremy Lichtman

- Teresa Lien

- Alan R. Light

- Malak Trabelsi Loeb

- Longevity

- Melvin Louis

- Ivan Lovric

- Dan Lovy

- JK Lund

- Mike Lustgarten

- Teresa Lynn

- Donald Maclean

- Alexander MacRae

- Pat Maechler

- Shahriar Mahmud

- Narendra Malewar

- Kiran Manam

- Jeremy Mancuso

- Jake Mann

- John Mardlin

- Thierry Marianne

- Lori Marino

- John Marlowe

- Kaiser Matin

- Andreas Matt

- Clark Matthews

- Frankie May

- Michael Walton McAnally

- Chris Mcaulay

- Tom McCabe

- Paul McGlothin

- Jamie McGuigan

- Matt McGuirl

- Joe McKinney

- Roman Mednitzer

- J.P. Medved

- Zack Miles

- Cathy Miller

- Elena Milova

- Josh Mitteldorf

- Alireza Mokri

- Marco Monfils

- Poopeh Morakkabati

- Peter Morgan

- Tatiana Moroz

- Paul Moscarella

- Victor V. Motti

- Thomas Munyon

- B.J. Murphy

- Jeff Myers

- Ramez Naam

- Mark Nall

- Unni Neel

- Caycee Dee Neely

- Sara Negar

- Steve Nerlich

- The Neuro-Network

- Steve Nichols

- Danko Nikolic

- David Nordfors

- Florence Nsiah

- Johan Nygren

- Nikki Olson

- Ours Ondine

- David Orban

- David Orrell

- Ken Otwell

- Jeffery Pacheco

- Steven Palter

- Mark Parkins

- Carla Parsons

- Eithen Pasta

- Ira S. Pastor

- Emanuel Yi Pastreich

- Michael Paton

- Ian D. Pearson

- Carse Peel

- Justin Penrose

- George Perry

- Jimmé Peters

- Michael Phillips

- Jim Pinkerton

- Federico Pistono

- Nicholas Play

- Thomas M. Powers

- Robert James Powles

- Shailesh Prasad

- Nonthapat “Brave” Pulsiri

- Walter Putnam

- Jimmy Quaresmini

- Vjekoslav Radišić

- Raphael Ramos

- Joseph Rampolla

- Yurii Rashkovskii

- Daniel W. Rasmus

- Mean Raven

- Philip Raymond

- Roderick Reilly

- Bill Retherford

- Michael Graham Richard

- Maico Rivero

- Germen Roding

- Alexander Rodionov

- Saúl Morales Rodriguéz

- Len Rosen

- Xavier Rosseel

- Martine Rothblatt

- Fyodor Rouge

- Asim Roy

- Roy

- Shubham Ghosh Roy

- Mike Ruban

- Pasha Rudenko

- Otto E. Rössler

- Mark Sackler

- Bob Sampson

- Laura Samsó

- Albert Sanchez

- Rosalind Sanders

- Magaly Santiago

- Maria Santos

- Julian Sapp

- Richard Christophr Saragoza

- Roland Schiefer

- Johan Scholtz

- Frank Schueler

- Eric Schulke

- Dirk Schulze-Makuch

- Seb

- Josh Seeherman

- Myra Sehar

- Brandon Seifert

- Quinn Sena

- Daniel Shafrir

- Arzu Al Siam

- Jamal Simpson

- Amalie Sinclair

- Eli Sklar

- Chris Smedley

- Andrew Smith

- James Christian Smith

- Rick Smyre

- Mike Snead

- Rx Sobolewski

- Tom Soetebier

- Benjamin T. Solomon

- Claudio Soprano

- Bruno Henrique de Souza

- Nova Spivack

- Chavis Srichan

- Oliver Starr

- Jason Stone

- Frank Sudia

- Takayuki Sugano

- Daniel Sunday

- Cecile G. Tamura

- Anderson Tan

- Sergio Tarrero

- Gemechu Taye

- Michael Taylor

- Wise Technology

- Reno J. Tibke

- Art Toegemann

- Laurence Tognetti

- Tihamer "Tee" Toth-Fejel

- Patrick Tucker

- Alexei Turchin

- Zachary Urbina

- Paul Velho

- Aaron Vesey

- Clément Vidal

- Prem Vijaywargi

- Alex Vikoulov

- Natasha Vita-More

- Paul M. Vittay

- Aleksandar Vukovic

- Glenn A. Walsh

- Frans van Wamel

- Brian Wang

- Simon Waslander

- TJ Wass

- Jaysen West

- Matthew White

- Alexandra Whittington

- Marcia Wiegand

- Keith Wiley

- J.R. Willett

- Samson Williams

- Chima Wisdom

- Müslüm Yildiz

- TJ Yoo

- Tomer Ze'ev

Comments are closed.