Mar 3, 2023

Growing Microchips Inside the Brain

Posted by Dan Breeden in categories: computing, neuroscience

Experiments in live zebrafish and leeches may one day lead to growing chips in living tissue.

Experiments in live zebrafish and leeches may one day lead to growing chips in living tissue.

When two forms of hydrogen smash together an unusual process called quantum tunnelling can occur. Researchers have now worked out how rarely it happens.

Poor sleep could lead to between two and seven years worth of heightened heart disease risk and even premature death, according to a new study led by researchers at the University of Sydney in collaboration with Southern Denmark University.

The study analyzed data from more than 300,000 middle-aged adults from the UK Biobank and found that different disturbances to sleep are associated with different durations of compromised cardiovascular health later in life compared to healthy sleepers.

In particular, men with clinical sleep-related breathing disorders lost nearly seven years of cardiovascular disease-free life compared to those without these conditions, and women lost over seven years. Importantly, even general poor sleep, such as insufficient sleep, insomnia complaints, snoring, going to bed late, and daytime sleepiness is associated with a loss of around two years of normal heart health in men and women.

On March 1 and 2, Jupiter and Venus will appear side by side in the night sky in an event called a conjunction, which is visible without a telescope or binoculars.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h8H2r48Ljts

On Thursday, March 2 at 12:34 a.m. ET (12:34 UTC), Falcon 9 launched Dragon’s sixth operational human spaceflight mission (Crew-6) to the International Space Station from Launch Complex 39A (LC-39A) at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Following stage separation, Falcon 9’s first stage landed on the Just Read the Instructions droneship.

Dragon will autonomously dock with the space station on Friday, March 3 at approximately 12:43 a.m. ET (5:43 UTC). Follow Dragon and the crew’s flight below.

Continue reading “NASA’s SpaceX Crew-6 Mission | Approach and Docking with ISS LIVE” »

For windows 11 users.

New features make it easier than ever to find what you need and connect to what’s important.

Continue reading “Introducing the new Bing in Windows and More” »

Imagine a sheet of material just one layer of atoms thick—less than a millionth of a millimeter. While this may sound fantastical, such a material exists: it is called graphene and it is made from carbon atoms in a honeycomb arrangement. First synthesized in 2004 and then soon hailed as a substance with wondrous characteristics, scientists are still working on understanding it.

Postdoc Areg Ghazaryan and Professor Maksym Serbyn at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) together with colleagues Dr. Tobias Holder and Professor Erez Berg from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel have been studying graphene for years and have now published their newest findings on its superconducting properties in a research paper in the journal Physical Review B.

“Multilayered graphene has many promising qualities ranging from widely tunable band structure and special optical properties to new forms of superconductivity—meaning being able to conduct electrical current without resistance,” Ghazaryan explains.

The iconic X-shaped organization of metaphase chromosomes is frequently presented in textbooks and other media. The drawings explain in captivating manner that the majority of genetic information is stored in chromosomes, which transmit it to the next generation. “These presentations suggest that the chromosome ultrastructure is well-understood. However, this is not the case,” says Dr. Veit Schubert from IPK’s chromosome structure and function research group.

Several models have been proposed to describe the higher-order structure of metaphase chromosomes based on data obtained using a range of molecular and microscopy methods. These models are categorized as helical and non-helical. Helical models assume that the chromatin in each sister chromatid at metaphase is arranged as a coil, whereas non-helical models suggest that chromatin is folded within the chromatids without forming a spiral.

The researchers revived the term “chromonema,” which was used for the first time at the beginning of the 20th century. Now, the IPK and IEB researchers provided a detailed description of its ultrastructure. Different experimental approaches, including chromosome conformation capture sequencing (Hi-C) of isolated mitotic chromosomes, polymer modeling, and microscopic observations of sister chromatid exchanges and oligo-FISH labeled regions at the super-resolution level provided an independent proof for the coiling of the chromonema.

Researchers from the University of Oxford have contributed to a major international study which has captured a rare and fascinating space phenomenon: binary star systems. The study, “A shared accretion instability for black holes and neutron stars,” has been published in Nature.

Scientists have long been intrigued by X-ray binary star systems, where two stars orbit around each other with one of the two stars being either a black hole or a neutron star. Both black holes and neutron stars are created in supernova explosions and are very dense—giving them a massive gravitational pull. This makes them capable of capturing the outer layers of the normal star that orbits around it in the binary system, seen as a rotating disk of matter (mimicking a whirlpool) around the black hole/neutron star.

According to theoretical calculations, these rotating disks should show a dynamic instability: about once an hour, the inner parts of the disk rapidly fall onto the black hole/neutron star, after which these inner regions re-fill and the process repeats. Up to now, this violent and extreme process had only been directly observed once, in a black hole binary system. For the first time, it has now been seen in a neutron star binary system, called Swift J1858.6–0814. This discovery demonstrates that this instability is a general property of these disks (and not caused by the presence of a black hole).

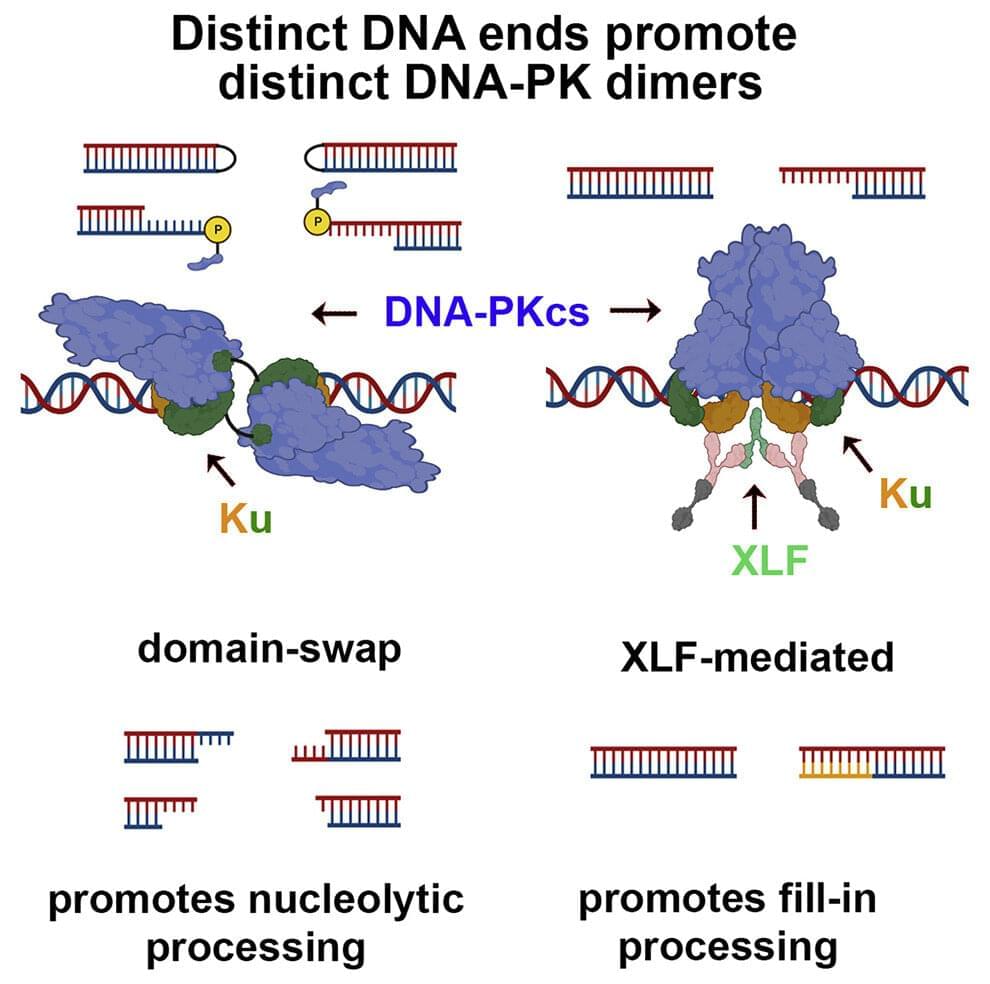

A team of researchers from Michigan State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine has made a discovery that may have implications for therapeutic gene editing strategies, cancer diagnostics and therapies and other advancements in biotechnology.

Kathy Meek, a professor in the College of Veterinary Medicine, and collaborators at Cambridge University and the National Institutes of Health have uncovered a previously unknown aspect of how DNA double-stranded breaks are repaired.

Continue reading “DNA repair discovery could improve biotechnology” »