Feb 5, 2016

This new soft robotic gripper can gently pick up objects of practically any shape

Posted by Shailesh Prasad in categories: biotech/medical, cyborgs, food, robotics/AI, space

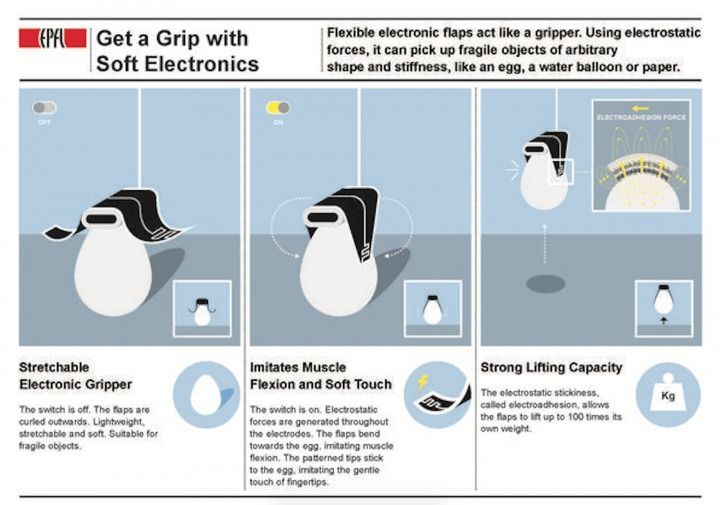

Robots aren’t exactly known for their delicate touch, but soon, the stereotype of the non-gentle machine may change. Scientists say they have managed to develop a robot with “a new soft gripper” that makes use of a phenomenon known as electroadhesion — which is essentially the next best thing to giving robots opposable thumbs. According to EPFL scientists, these next-gen grippers can handle fragile objects no matter what their shape — everything from an egg to a water balloon to a piece of paper is fair game.

This latest advance in robotics, funded by NCCR Robotics, may allow machines to take on unprecedented roles. “This is the first time that electroadhesion and soft robotics have been combined together to grasp objects,” said Jun Shintake, a doctoral student at EPFL. Potential applications include handling food, capturing debris (both in space and at home), or even being integrated into prosthetic limbs.