Jan 22, 2020

Physicists Develop Reversible Laser Tractor Beam Functional Over Long Distances

Posted by Quinn Sena in categories: entertainment, particle physics, space travel, tractor beam

Circa 2015

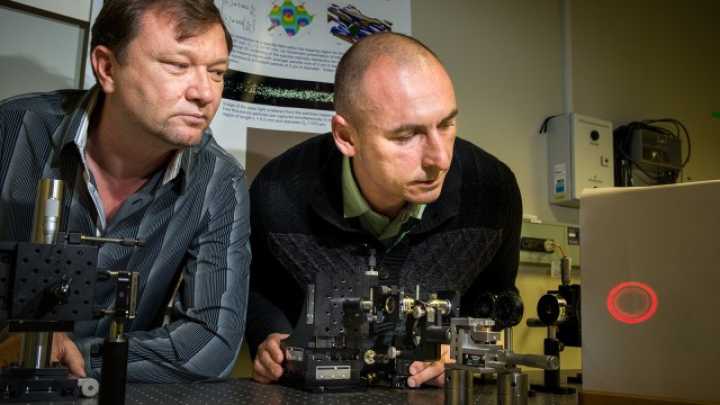

Spaceships in movies and TV shows routinely use tractor beams to tow other vessels or keep them in place. Physicists have been hard at work trying take this technology from science fiction to reality. Significant process has recently been made by a team who have developed a laser tractor beam able to attract and repel particles about 100 times further than has been previously achieved. The lead author of the paper, published in Nature Photonics, is Vladlen Shvedov at Australian National University in Canberra.

Other recent tractor beams have used acoustics or water, but this one uses a single laser beam to control tiny particles about 0.2 millimeters in diameter. The tractor beam was able to manipulate the particles from a distance of 20 centimeters, shattering previous records. Despite this incredible distance, the researchers claim it is still on the short end of what is possible for this tractor beam technique.

Continue reading “Physicists Develop Reversible Laser Tractor Beam Functional Over Long Distances” »

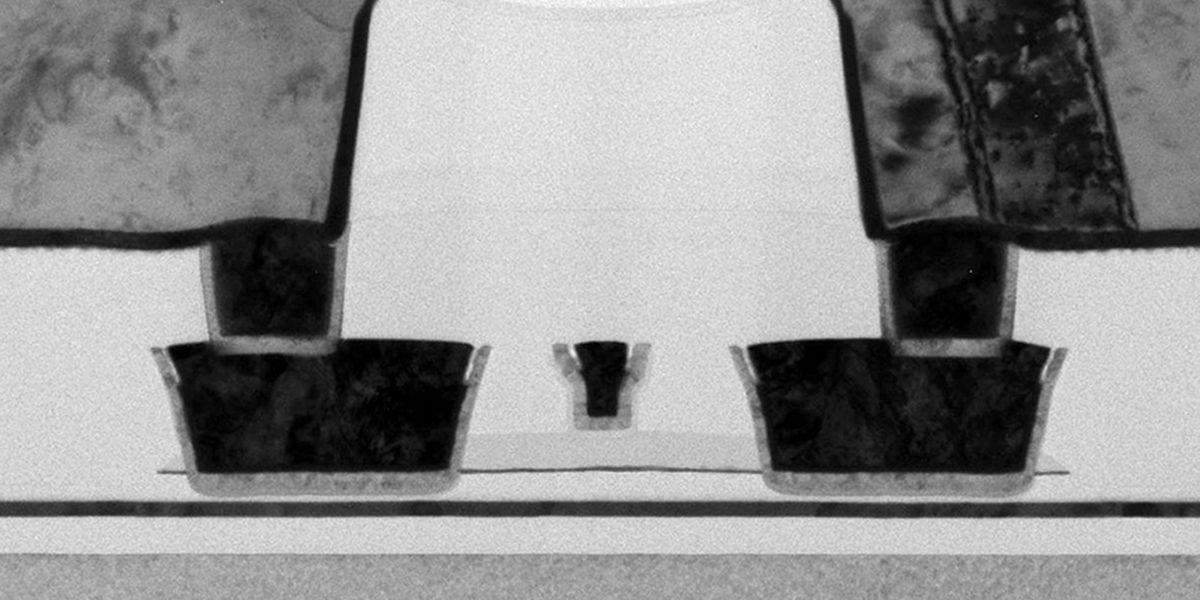

Devices made with 2D semiconductors might start to appear sooner than you expected.

Devices made with 2D semiconductors might start to appear sooner than you expected.