Mar 28, 2024

The virus that infects almost everyone, and its link to cancer and MS — podcast

Posted by Shubham Ghosh Roy in categories: biotech/medical, neuroscience

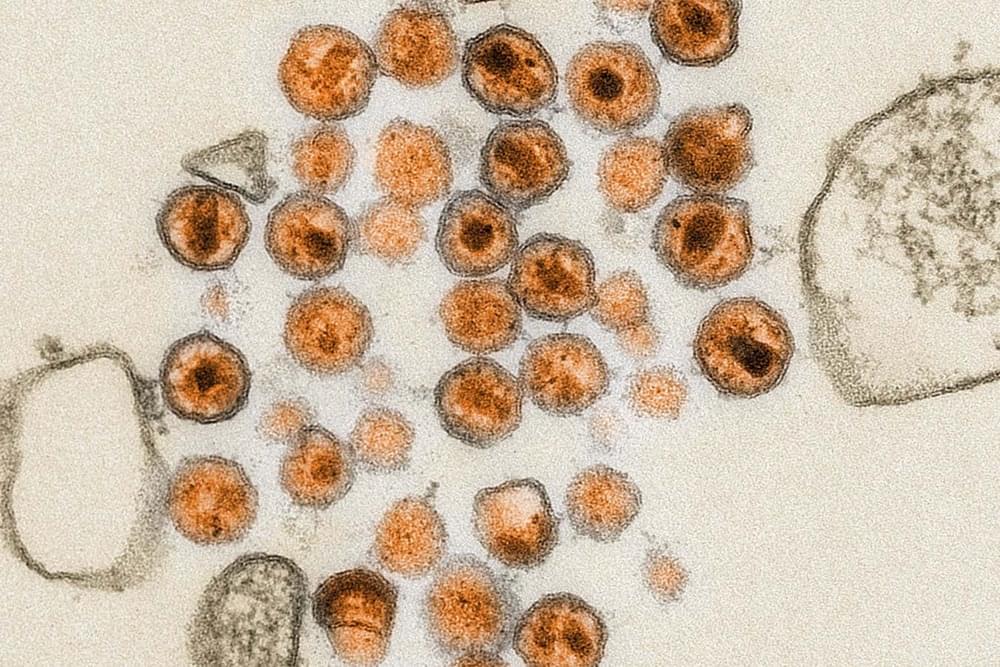

On 28 March it’s the 60th anniversary of the discovery of Epstein-Barr virus, the most common viral infection in humans. The virus was first discovered in association with a rare type of cancer located in Africa, but is now understood to be implicated in 1% of cancers, as well as the autoimmune disease multiple sclerosis. Ian Sample meets Lawrence Young, professor of molecular oncology at Warwick Medical School, to hear the story of this virus, and how it might help us prevent and treat cancer and other illnesses.