Loosening the Linkages Between Language and the Land

by Lifeboat Foundation Advisory Board members Lawrence Baines and Gul Nahar.

Abstract

Like any living thing, languages evolve over time. This paper examines the connections among sociocultural change, access to the Internet, and the fluctuations of English as a global language. English has begun to transcend geographical borders and sociocultural boundaries as its status as a national language, official language, or unofficial language grows. Connections among various phenomena, such as Internet penetration, language policy, and linguistic diversity, and economic well-being, are analyzed. Countries discussed include South Korea, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania, Tunisia, Japan, and China.

The rush of governments worldwide to connect their citizens to the mobile Internet and to adopt English as a language of commerce comes with the expectation that an enhanced quality of life will be an inevitable outcome. However, the proliferation of English as a global language and the widespread adoption of the Internet are transmogrifying the roles of indigenous languages and local customs. The contention of the authors is that these transformative events — the global spread of English and the proliferation of the Internet — are loosening the historically durable ties between the geography of a region and the language and customs of the people who live there.

Language and Geography

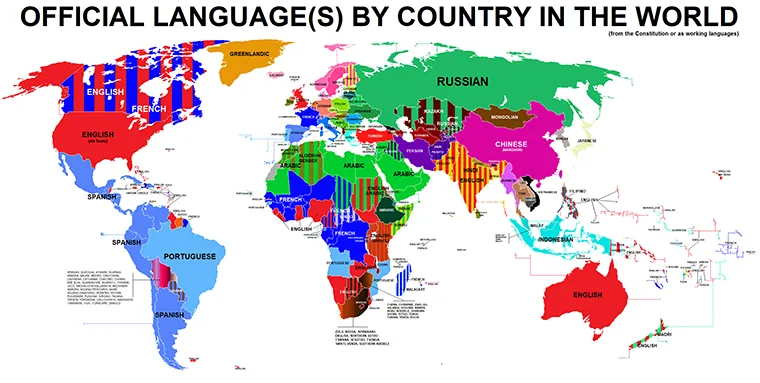

Traditionally, languages have been defined in geographic terms. The assumption always has been that words and meanings are inextricably connected to the land and its people. The names of language families, themselves, are reflective of the geography of the regions where languages were born and have thrived.

The Indo-European family of languages, for example, include over 400 languages and dialects and are associated with current-day Europe and parts of Asia, including India (Haak et al. 2015). The largest language family on the continent of Africa in terms of geographic area is Niger-Congo, which includes about 1400 languages and is associated with the countries of Central and Southern Africa (Niger-Congo languages 2015).

About the link between language and geography, Chambers (2000: 170) writes:

Eighteenth century philosophers believed that language was a natural, organic entity, like a plant, and its diversity was thought to have the same source as the diversity of vegetation. Just as vegetable life took on distinctly different appearances according to the climate and soil that nourished it, so languages took on distinctly different characteristics in different climates.

With the advent of mass transportation and the proliferation of mobile, global communications, the connection between language and the land may be loosening. Today, two of every seven persons on planet Earth speak English, and the number seems likely to increase over the next 50 years (Baines 2012; Westcombe 2011). Needless to say, it is difficult to substantiate the proliferation of English using arguments solely predicated upon national boundary lines or physical features of a landscape.

In the country of South Korea in East Asia, for example, English is widely spoken and taught in schools, though the country shares no borders with countries where English is the primary language. Of course, the US military, along with the United Nations Peacekeeping Forces, worked with the government of South Korea during the Korean War, 1950–1953. However, South Korea has no history of colonization by English-speaking people, other than a trickle of religious evangelists (Chung 2014).

English in East Asia

In many countries of East Asia, proficiency in English is viewed as a gateway to economic success. English proficiency is considered desirable by most citizens who want a higher standard of living and by national governments attempting to promote growth and financial stability. For better or worse, the presence of English language education in East Asian countries pits the rewards associated with increased trade against the preservation of native languages, cultural identity, and local traditions.

Since the 1970s, the initiative to integrate English language instruction into the Chinese educational system has been a priority for the central government’s modernization agenda (Hu and McKay 2012).

China’s Ministry of Education has already mandated formal primary English instruction beginning in the elementary years, but recent initiatives have expanded English instruction into kindergarten, where bilingual classes are now offered in a variety of venues (Feng 2005; Deloitte China Research and Insight Center 2014). At the same time, Chinese universities have begun to offer courses exclusively in English (Yan et al. 2015).

In 2013, there were over 50,000 English language schools in China, and the English language learning industry in China generated about 5 billion dollars (Adkins 2014: 9). Incredibly, with as many as 400 million English language learners in China, there may be more speakers of English in China than in the United States (Wei and Jinzhi 2012).

In Japan, English is viewed as a necessary second language for participation in both business and research. As a result, English as a course of study has customarily begun in fifth grade in Japan and has continued well into the university curriculum. However, the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT) recently has announced that the teaching of English will commence even earlier — in grade 3 — to insure better English language acquisition at an earlier age (Yoshida 2013).

About the explosive advance of English in East Asia, Education First (2015: 27), an organization that publishes an annual report that rates countries in terms of their adoption of English, reports that:

Since 2007, Asia’s adult English proficiency has improved more than any other region. With half of the world’s population, Asia has wide-ranging levels of proficiency…. With their increasingly international economies, Asian countries invest in English training as a tool for accelerating globalization.

In countries of at least five million in population, the top 8 most prosperous countries in the world in terms of per person income are all predominantly English-speaking, as noted in Table 1.

Country |

Rank in GNIPPb |

2014 GNIPP |

Population |

% who speak English |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Norway |

1 |

103,050 |

5.2 million |

90 |

Australia |

2 |

64,680 |

24 million |

97 |

Sweden |

3 |

61,600 |

9.8 million |

86 |

Denmark |

4 |

61,310 |

5.7 million |

86 |

United States |

5 |

55,200 |

94 |

|

Singapore |

6 |

55,150 |

5.6 million |

80 |

Canada |

7 |

51,690 |

36 million |

86 |

Netherlands |

8 |

51,210 |

17 million |

90 |

Japan |

13 |

42,000 |

127 million |

50+ (proficiency varies widely) |

South Korea |

17 |

27,090 |

49 million |

50+ (proficiency varies widely) |

|

aIncludes countries with at least five million inhabitants plus Japan and South Korea; Atlas Method; 2015 US dollars. bAccording to Global Finance Magazine (2015), gross national income per person is “gross national income divided by population” and is used as a relative wealth index for citizens of a country. |

||||

Although Japan and South Korea are not in the top 8 in terms of GNIPP, both countries are economic powerhouses and are among the top 20. The percentage of English speakers in both countries has expanded markedly over the past 30 years, with younger citizens increasingly more proficient in English than their elders (Kim and Kim 2011).

The lowest-ranked countries in the world with regard to GNI per capita are listed in Table 2. Notably, none of the bottom-eight countries are located in Asia nor is English widely spoken in any of them.

Country |

Rank in GNIPP (186 countries) |

2014 GNIPP |

Population |

% who speak English |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Central African Republic |

Last |

600 |

5 million |

0–1 |

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) |

Next to last |

650 |

77 million |

0–1 |

Burundi |

Third from last |

770 |

9.8 million |

0–1 |

Malawi |

Fourth from last |

790 |

16 million |

4 |

Niger |

Fifth from last |

920 |

0–1 |

|

Guinea |

Sixth from last |

1120 |

11 million |

0–1 |

Mozambique |

Seventh from last |

1140 |

26 million |

0–1 |

Togo |

Eighth from last |

1290 |

7.3 million |

0–1 |

|

aIncludes countries with at least five million inhabitants; Atlas Method; 2015 US dollars |

||||

It is only natural for nations who wish for greater economic development to infer a causal relationship between the ability of a country’s population to speak English and the relative wealth of the populace. Indeed, the data in Tables 1 and 2 seem to indicate a strong correlation between prosperity and large numbers of citizens who are conversant in English.

To get a better sense of how English might function as an official second language within an East Asian country, a more in-depth examination of South Korea may prove illuminating. Indeed, South Korea seems to have adopted English as a logical policy choice, with the express objectives of promoting innovation and making money. According to Nicholson (2015: 13), the English language in South Korea is not “imperialistic,” but is “pragmatic,” and related to “purposes of international business communication and academic advancement.”

It was not so long ago that South Korea was considered a “developing country” (Connolly and Yi 2008). In 1961, South Korea’s gross domestic product per capita was only $91 (World Bank 2015a), significantly less than Sri Lanka ($143), Peru ($273), and less than one-fifth of the GDP per capita of the Democratic Republic of the Congo ($563). By 2014, South Korea’s gross domestic product per capita had grown to $27,970, which was comparable to the output of France or Japan and surpassed the Democratic Republic of the Congo ($1429), Sri Lanka ($3631), and Peru ($6551) by significant margins. Although there are many factors involved in South Korea’s stunning economic ascent, technology and language have been critical, unifying factors for the country.

In addition to the Korean language, the study of English is a required course for Korean students every year, from grade 3 to grade 12 (Korean Ministry of Education 2015). Hadid (2014) found that Koreans spend on average “$15 billion on private English education, with 17,000 English cram schools (known as hagwons) scattered across the nation and an army of 30,000 native English teachers, along with thousands more who teach English illegally.” Today, over half of Koreans under the age of 40 understand basic English, and 10% consider themselves fluent (Hadid 2014), a marked contrast to a few decades ago when almost no South Koreans, outside of military advisors to the United States, spoke English (Kim and Kim 2011).

In addition to the adoption of English, South Korea has made deep monetary and policy commitments to technology. As a result, South Koreans are among the highest users of the Internet on the planet, and the country’s technological sector has become one of the world’s most formidable in terms of productivity and distribution (World Bank 2015a). The proliferation of technology and the elevation of the English language have helped speed the sociocultural transformation of South Korea from an “impoverished nation just out of war” to a flourishing world power in less than a half-century (Da-ye 2012).

The Technological Infrastructure of the Internet

Arpanet (Advanced Research Projects Agency Network) was the original Internet, developed by the Department of Defense in the United States. As a result of its American origins, the infrastructure of the Internet was written in English-based code, as are the vast majority of programming languages that proliferate on the Internet today. English is so prevalent as the language of the Internet that developers from all over the world are as likely to consult English style handbooks as highly technical programming manuals. Ford (2015) writes:

Style and usage matter; sometimes programmers recommend Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style — that’s right, the one about the English language. Its focus on efficient usage resonates with programmers. The idiom of a language is part of its communal identity.

Of the more than 30 trillion web pages on the Internet, about 56% are in English, while only 6% are in German, 5% in Japanese, and 3% in Chinese (Phillips 2015). According to The Economist (2015: 5), “American firms now host 61% of the world’s social-media users, undertake 91% of its searches and invented the operating systems of 99% of its smartphone users.” Along with the Internet’s infrastructure and the litany of programming languages, the words used to communicate on the Internet are likely to be English, as well.

The impact of an English-based Internet has had fascinating effects

on other languages. Arabizi, for

example, is a system of writing in Arabic that uses Latin-type letters

rather than Arabic script. The word Because

of the ubiquity of QWERTY keyboards and the “westernized” nature of

interfaces on the Internet, speakers of Chinese have adapted their

communications by writing in pinyin, which uses the Latin alphabet as a

vehicle to communicate in Chinese (Information Today 1998).

In actuality, pinyin was introduced by China’s revolutionary government

in 1958, and its original use was as a way to teach “correct sounds and

tones” to young children before introducing the complexities of writing

Chinese characters by hand (Byrne 2007: 201). However, pinyin has become the lingua franca of Chinese on the Internet. Unfortunately,

much recent research substantiates that an increasing reliance on the

Roman-based pinyin system has had deleterious effects on the ability of

Chinese children to write Chinese characters (Tan et al. 2013; The Economist 2014). Despite the alarm over “character amnesia,” according to Mair (2012),

the Chinese language is not dying but adapting. A Chinese interlocutor

who writes to a friend will probably write in pinyin. A Chinese

interlocutor who composes a text in Mandarin for a professor of Chinese

literature will probably use carefully chosen Chinese characters. The top 18 countries in the world (with a population of at least five

million citizens) in terms of Internet connectivity are shown in Table

3. Rank Country Users per 100 people % who speak Englishb 1 Norway 96.3 90 2 Denmark 96.0 86 3 Netherlands 93.2 90 4 Sweden 92.5 86 5 Finland 92.4 70 6 United Kingdom 91.6 98 7 Japan 90.6 50 8 90.4 80c 9 United States 87.4 94 10 Canada 87.1 86 11 Switzerland 87.0 61 12 Germany 86.2 64 13 Belgium 85.0 59 14 Australia 84.6 97 15 South Korea 84.3 50 16 France 83.8 39 17 Singapore 82.0 80 18 Austria 81.0 73 aIncludes

countries with over five million persons bEducation

First (2015), European Commission (2012), Ethnologue (2015), and

Nicholson (2015) cThis data was

taken from Arab Social Media Report (2012); however,

it is important to note that, since 80% of the UAE population at any

point in time might be comprised of immigrants, this percentage is only

an estimate The connection between technology

and the English language is evident in the number of countries listed

in Table 3 where English is dominant. Note that 13

of the 18 most connected nations in the world have 70% or more English

speakers. In the other five countries, 39–64% of residents are

able to communicate in English. That the

English language and technological innovation have become associated

with economic development has not gone unnoticed. Since 2007, the

government of Tanzania, for example, has tried to speed the adoption of

technological devices among its citizens through the exemption of taxes

on imported technology equipment (Sife et al. 2007), one of the strategies often utilized by the

South Korean government to promote technology spending. The government

of Tanzania has also sponsored the development of SEACOM, an

optic-fiber, marine cable that has increased bandwidth and reduced

telecommunication costs by 95% for Tanzanian citizens (Swarts and

Wachira 2010; Lwoga 2012).

While many Africans have no access to the Internet (the bottom-eight

countries in Table 3 are all from Africa), as many

as 20% of Tanzanians could access the Internet in 2013, which

represents rapid growth in only a few years (Mtweve 2014). Currently, in Tanzania, most residents

speak Kiswahili, and only a small percentage of the population speaks

English. Despite the adoption of Kiswahili as the national language,

English has become the language of the educated elite (Hillard 2015). Tanzanians who speak English often have some

affiliation with expensive, private schools in the country, who deliver

the curriculum almost exclusively in English. To encourage more

Tanzanians to develop competency in English, the government has

instituted a series of policies, including the edict that high schools

and postsecondary institutions must use English as the basic language

of instruction. About the edict to begin teaching courses in English,

Qorro (2013) notes that one problem might be that

most students are unfamiliar with the language: A second difficulty with delivering

courses in English is, of course, that proficiency in English is

presumed of Tanzanian teachers. However, surveys of English language

proficiency among Tanzanian teachers have revealed that a large

percentage struggle to speak or write in English and, thus, would be

unable to coherently convey the content of their subject matter to

students in English (Nunan 2003; Qorro 2013). As most Tanzanians speak a local dialect

as a first language, Kiswahili and English act as the second and third

languages, respectively. However, because 95% of the population is

fluent in Kiswahili (Brock-Utne and Holmarsdottir 2004), at least there is a common language from which

to launch a move to English. The lack of a unifying, national first

language makes conversion to any second language exponentially more

difficult (more about this in the discussion of the Democratic Republic

of the Congo below). Undeniably, the rise of English is affiliated with

increased wealth, though it simultaneously imperils the 120 dialects

spoken by different groups in Tanzania (Hardman et al. 2012). Tunisia is yet another example of an

African country that is moving toward English, while its native and

colonial languages are in flux. Three thousand years ago, the people of

the geographic area that is now Tunisia spoke Berber, Punic, and Latin.

With the spread of Islam in the eighth century, Arabic became the

dominant language, gradually replacing Berber and other languages and

dialects. Today, Berber is spoken by less than 1% of Tunisians (Daoud

2011). During the period in which Tunisia was a

French Protectorate (1881–1956), the French language surged,

becoming the default second language, behind Arabic (Gibson 2013). Today, English is systematically becoming

integrated into the culture of multilingual Tunisia. In fact, English

has become a mandatory subject in the school curriculum from the sixth

grade on. The use of English in Tunisian society is conspicuous in

science, technology, economics, and social sciences (Daoud 2011). Increasingly, younger Tunisians and academics

are using the English language, rather than Arabic or French, to

discuss contemporary intellectual, political, and social issues

(Labassi 2008). It is no accident that the plethora

of tweets and instant messages sent by Tunisians during the intense

months of the Arab Spring in 2011 were mostly written in English (Bruns

et al. 2013). Perhaps the most interesting case study in

Africa at this moment in time is the Democratic Republic of the Congo,

formerly known as the Republic of Zaire. Incredibly, the per capita

gross domestic product of the DRC was five times that of South Korea in

1961, but the DRC has since lost its advantage (World Bank 2015c). In 2013, the country was rated 186th of 187

countries by the United Nations in terms of human development. Almost

nine of ten citizens live in severe poverty, which means that they live

on less than $1.25 per day. The DRC ranks relatively low in terms of

literacy but high in terms of death rates, income inequality,

discrimination, and crime (United Nations Human Development Index 2013). Researchers from the World Bank (2015b) note:

As in

Tunisia, French is the official language of the DRC, though over 200

languages are spoken and there are four additional

“national” languages: Lingala, Kingwana (another dialect of

Swahili), Kikongo, and Tshiluba (World Factbook 2015). According to the Language Education Policy

Studies website (2015), in the DRC:

Although French is the language of

the government, courts, and commerce, only about one in three of

DRC’s citizens actually speak French (Organisation Internationale

de Francophonie 2015). While South Korea

has one of the highest Internet penetration rates in the world, the DRC

has one of the lowest (Internetlivestats 2015;

World Bank 2015b). Table 4

compares South Korea and the Democratic Republic of the Congo in terms

of population, land area, income, English speakers, and Internet

penetration. The top 18 countries in the world (with a population of at least five

million citizens) in terms of Internet connectivity are shown in Table

3. There

seems to be universal agreement that, at least in terms of natural

resources, the Democratic Republic of the Congo is one of the richest

countries on Earth (World Factbook 2015; World Bank

2015c). In comparison, Korea, despite having 30

million fewer people, scarcer natural resources, and less than 5% of

the land mass, has a per capita gross national product that is 64 times

greater. Obviously, South Korea’s technological infrastructure

and economic development have grown at far faster rates than those of

the DRC. In addition, South Koreans communicate using a single,

unifying language – Korean, with English as a de facto secondary

language, a widely adopted language of commerce and academics. Not only

are many courses delivered in English in K–12 schools in South

Korea, current president Park Geun-hye often makes political speeches

to her constituents in English (Davis 2015). In the Democratic Republic of the Congo,

languages and personal identities are far more convoluted. Citizens in

some areas may not be able to comprehend the language of citizens who

live only a short distance away. In light of the expansion of English

as the global language of commerce, English as an official language was

considered by the government of the DRC in 2010, but the idea has never

been taken seriously as a potential policy change (Kasanga 2012). The diversity of languages has impeded

communication within the country as well as slowed trade and diplomatic

relations with other nations. As a result, the Democratic Republic of

the Congo is one of the poorest countries in the

world. Developing countries worldwide are

considering adopting English as an official language or, at least,

encouraging its widespread use. Pinon and Haydon (2010: 5) note the assumptions of financial rewards

implicit in the adoption of English by developing countries, even if it

means the denigration of native dialects and the evisceration of

colonial languages, such as French or Spanish: Creating governmental policies to

promote English as an official language does not automatically

translate into increased wealth and satisfaction. The Republic of

Liberia, with a population of 4.5 million, is one of the poorest

countries in the world, though as many as 20% of Liberians speak

English (World Factbook 2015). Despite the

inconclusive evidence on behalf of English as a liberating,

money-generating language, resistance to its spread may be futile.

Education First (2015: 4) notes that the connection

between English and economic well-being has become an entrenched

belief: Once upon a time, geography

and the exigencies of travel had significant delimiting effects upon

language and communication. People who were born and grew up in a

remote village in New Guinea, for example, would seldom leave the

geographic area associated with their settlement for two very good

reasons:

The residents of other villages might not understand them. The residents of the other villages might

try to kill them (Diamond 2012). According

to the Groupe Speciale Mobile Association (2014:

3), the number of persons who will have access to the mobile Internet

will rise to 3.8 billion — more than half of the world’s

population — by 2020. The continued expansion of the

English-language-based Internet to an ever wider global market will

only accentuate the desirability, if not urgency, of learning the

language. Worries over the spread of English abound, chief among

them the demise of language diversity and the potential dilution of

local traditions. According to a UNESCO report on endangered languages,

“A language disappears when its speakers disappear or when they

shift to speaking another language — most often, a larger

language used by a more powerful group” (UNESCO 2015). Over the next few decades, hundreds of

languages are expected to disappear forever, and the rate of extinction

is expected to accelerate (Baines 2012; Harrison 2007). If, as prognosticated, the world begins

moving to the Internet of Things and machines are networked so that

they communicate with each other continually, then the operation of

many aspects of our lives, “from streetlights to seaports,”

would depend upon effective machine communication (Burrus 2014). It seems inevitable that the language of these

powerful machines and the language acceptable to their human/machine

interface will be some form of English. Kornai (2013: 10) writes: Herscovitch (2012) comments: The future of

communications is the Internet and the language of the Internet is

English. However, even English is changing, morphing into Leetspeak (a

computerized English slang), Chinglish (Chinese and English), Spanglish

(Spanish and English), Babu English (Bengali and English), and Sheng

(Swahili and English). Language evolves to suit the purpose of the

messenger. As the Internet removes the obstacle of distance and the

rules for global conversation become increasingly standardized through

English, the influence of geography on language will continue to

weaken. Adkins, S. (2014). The 2013–2018 China digital English language learning market (Ambient Insight Country Report). Monroe: Ambient Insight. Retrieved from http://www.ambientinsight.com/Resources/Documents/AmbientInsight-2013-2018-China-Digital-English-Language-Learning-Market-Abstract.pdf. Arab Social Media Report. (2012). Social media in the Arab world: Influencing societal and cultural change? Dubai: Dubai School of Government. Google Scholar Baines, L. A. (2012). A future of fewer words? The Futurist, 46(2), 42–47. Google Scholar Brock-Utne,

B., & Holmarsdottir, H. B. (2004). Language policies and practices

in Tanzania and South Africa: Problems and challenges. International Journal of Educational Development, 24(1), 67–83. CrossRef Google Scholar Bruns,

A., Highfield, T., & Burgess, J. (2013). The Arab spring and social

media audiences: English and Arabic Twitter users and their networks. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(7), 871–898. CrossRefGoogle Scholar Burrus, D. (2014). The Internet of things is far bigger than anyone realizes. Wired. Retrieved from http://www.wired.com/insights/2014/11/the-internet-of-things-bigger/. Byrne, G. (2007). Schooling and learning difficulties in China. Contemporary Review, 289(1685), 201–208. Google Scholar Chambers, J. (2000). Region and language variation. English World-Wide, 21(2), 169–199. CrossRef Google Scholar Chung, B. J. (2014). A reflection on the growth and decline of the Korean Protestant Church. International Review of Mission, 103(2), 319–333. CrossRef Google Scholar Connolly, M., & Yi, K.-M. (2008). How much of South Korea’s growth miracle can be explained by trade policy? Philadelphia: Federal Reserve Bank. Retrieved from http://www.frbsf.org/publications/economics/papers/2008/wp08-23bk.pdf. Google Scholar Daoud, M. (2011). The sociolinguistic situation in Tunisia: Language rivalry or accommodation? International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 2011(211), 9–33. CrossRef Google Scholar Davis, J. H. (2015, October 16). Obama and South Korean leader emphasize unity. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/17/world/asia/park-geun-hye-washington-visit.html. Da-ye, K. (2012, October 7). How far can English go? The Korea Times. Retrieved from http://koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/biz/2012/10/602_121658.html. Deloitte China Research and Insight Center. (2014). Report on the diversification of China’s education industry. Shanghai: Deloitte China. Google Scholar Diamond, J. (2012). The world until yesterday: What can we learn from traditional societies? New York: Viking. Google Scholar Economist, The. (2014, August 23). Bad characters: Some Chinese forget how to write. Retrieved from http://www.economist.com/news/china/21613300-some-chinese-forget-how-write-bad-characters. Economist, The. (2015, October 3–9). American, the sticky superpower: A special report, 1–16. Google Scholar Education First. (2015). Education first English proficiency index. Retrieved from www.ef.com/epi. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. (2015). Open language archives in and about the English language. Retrieved from http://www.language-archives.org/language/eng. European Commission. (2012). Europeans and their languages report, special Eurobarometer 386. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_386_en.pdf. Feng, A. (2005). Bilingualism for the minor or the major? An evaluative analysis of parallel conceptions in China. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 8(6), 529–551. CrossRef Google Scholar Ford, P. (2015, June 11). What is code? Bloomsberg Businessweek. Retrieved from http://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2015-paul-ford-what-is-code/. Gibson, M. (2013). Dialect leveling in Tunisian Arabic: Towards a new spoken standard. In A. Rouchdy (Ed.), Language contact and language conflict in Arabic: Variations on a sociolinguistic theme (pp. 24–40). New York: Routledge. Google Scholar Global Finance Magazine. (2015). Definition of GNI per capita. Retrieved from https://www.gfmag.com/global-data/glossary/gdp-gni-definitions. Groupe Speciale Mobile Association. (2014). Digital inclusion. London: GSMA. Google Scholar Haak,

W., Lazaridis, I., Patterson, N., Rohland, N., Mallick, S., Llamas, B.,

& Khokhlov, A. (2015). Massive migration from the steppe was a

source for Indo-European languages in Europe. Nature, 522(7555), 207–211. CrossRefGoogle Scholar Hadid, A. (2014, June 29). The future of English in Korea. The Diplomat. Retrieved from http://thediplomat.com/2014/06/the-future-of-english-in-korea/. Hardman, F. C., Abd-Kadir, J., & Tibuhinda, A. (2012). Reforming teacher education in Tanzania. International Journal of Educational Development, 32, 826–834. CrossRef Google Scholar Harrison, K. D. (2007). When languages die: The extinction of the world’s languages and the erosion of human knowledge. New York: Oxford University Press. CrossRef Google Scholar Herscovitch, B. (2012, September 12). English is the language of the Asian century. The Drum. Retrieved from www.abc.net.au/news/2012-09-13/herscovitch-english-asia/4257442. Hillard. (2015). Tanzanian students’ attitudes toward English. TESOL Journal, 6(2), 252–280. CrossRef Google Scholar Hu, G., & McKay, S. L. (2012). English language education in East Asia: Some recent developments. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 33(4), 345–362. CrossRef Google Scholar Information Today. (1998). Library of Congress intends to convert to Pinyin system for Romanization of Chinese. Information Today, 15(1), 42. Google Scholar Internetlivestats (2015). Internet users by country (2014). Retrieved from www.internetlivestats.com/internet-users-by-country/. Kasanga, L. (2012). English in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. World Englishes, 31(1), 48–69. CrossRef Google Scholar Kim, K., & Kim, K. (2011). English in South Korea: Yesterday and today. In M. Koehler & P. Mishra (Eds.), Proceedings of society for information technology and teacher education international conference 2011 (pp. 2873–2882). Chesapeake: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). Google Scholar Korean Ministry of Education. (2015). National basic curriculum. Retrieved from http://english.moe.go.kr/web/1695/site/contents/en/en_0205.jsp. Kornai, A. (2013). Digital language death. PLoS One, 8(10), e77056, 1–11. CrossRef Google Scholar Labassi, T. (2008). On responsible uses of English: English for emancipation, correction and academic purposes. Changing English: Studies in Culture and Education, 15(4), 407–414. CrossRef Google Scholar Language

Education Policy Studies website. (2015). Language education policies

in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Retrieved from http://www.languageeducationpolicy.org/lepbyworldregion/africacongo.html. Lwoga, E. (2012). Making learning and Web 2.0 technologies work for higher learning institutions in Africa. Campus-Wide Information Systems, 29(2), 90–107. CrossRef Google Scholar Mair, V. (2012, August 30). Creeping romanization in Chinese. Language Log. Retrieved from http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=4157. Mtweve, S. (2014, March 23). Tanzania’s Internet users hit 9 m. The Citizen. Retrieved from http://www.thecitizen.co.tz/Business/Tanzania-s-Internet-users-hit-9m/-/1840414/2254676/-/dgt0ps/-/index.html. Nicholson, S. (2015). English as an international language: A functional role in South Korea. Journal for the Study of English Linguistics, 3(1), 13–27. CrossRef Google Scholar Niger-Congo languages. (2015). In Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from http://www.britannica.com/topic/Niger-Congo-languages. Nunan, D. (2003). The impact of English as a global language on educational policies and practices in the Asia-Pacific region. TESOL Quarterly, 37, 589–613. CrossRef Google Scholar Organisation Internationale de Francophonie. (2015). Democratic Republic of the Congo. Retrieved from http://www.francophonie.org/Congo-RD.html. Phillips, J. (2015, May 1). The Internet’s most popular languages. Brightlines. Retrieved from http://www.brightlines.co.uk/en-gb/brightlines/blog/2015/5/1/the-internets-most-popular-languages/. Pinon, R., & Haydon, J. (2010). English language quantitative indicators: Cameroon, Nigeria, Rwanda, Bangladesh and Pakistan. London: British Council. Retrieved from https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/sites/teacheng/files/Euromonitor%20Report%20A4.pdf. Google Scholar Qorro, M. (2013). Language of instruction in Tanzania: Why are research findings not heeded? International Review of Education, 59(1), 29–45. CrossRef Google Scholar Sife,

A. S., Lwoga, E. T., & Sanga, C. (2007). New technologies for

teaching and learning: Challenges for higher learning institutions in

developing countries. International Journal of Education and Development using Information and Communication Technology (IJEDICT), 3(2), 57–67. Google Scholar Swarts,

P.,, & Wachira, E. (2010). Tanzania: ICT in education situational

analysis. Global e-schools and communities initiative. Retrieved from http://www.gesci.org/assets/files/KnowledgeCentre/SituationalAnalysis_Tanzania.pdf. Tan,

L., Xu, M., Chang, C., & Siok, W. (2013). China’s language input

system in the digital age affects children’s reading development. Proceedings of the National Academy of the Sciences of the United States of America, 110(3), 1119–1123. CrossRefGoogle Scholar UNESCO. (2015). Endangered languages: Frequently asked questions on endangered languages. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/new/en/culture/themes/endangered-languages/faq-on-endangered-languages/. United

Nations Human Development Index. (2013). Congo (Democratic Republic of

the) HDI values and rank changes in the 2013 human development report.

Retrieved from http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/Country-Profiles/COD.pdf. Wei, R., & Jinzhi, S. (2012). The statistics of English in China. English Today, 28(3), 10–14. CrossRef Google Scholar Westcombe, J. (2011, September). English – a status report. Spotlight: Das Magazin fur Englisch (pp. 28–33). http://archiv.spotlight-online.de/files/spotlight/Magazine_content/Documents/spotlight_0911_28_30_crystal.pdf. World Bank. (2015a). Public data: World development indicators, GDP per capita for Japan, Korea, Peru, and Democratic Republic of Congo. World Bank. (2015b). Internet users (per 100 people). Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.P2. World Bank. (2015c). Democratic Republic of the Congo: Social context. Retrieved from http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/drc/overview. World Bank. (2015d). GNI per capita, PPP (current international $). Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.PP.CD?order=wbapi_data_value_2014+wbapi_data_value+wbapi_data_value-last&sort=desc. World Factbook. (2015). Democratic Republic of the Congo. Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/cg.html. Yaghan, M. A. (2008). “Arabizi”: A contemporary style of Arabic slang. Design Issues, 24(2), 39–52. CrossRef Google Scholar Yan,

E., Fung, I., Liu, L., & Huang, X. (2015). Perceived

target-language-use survey in the English classrooms in China:

Investigation of classroom related and institutional factors. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2015.1029934. Yoshida, R. (2013, October 13). Required English from third grade eyed. Japan Times. Retrieved from http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2013/10/23/national/required-english-from-third-grade-eyed/#.VMviRXB4rzE).…due

to the advancement of the Internet and the global use of the English

language (and without any imperialistic implications) the use of Latin

letters to write Arabic over the Internet and on text-messaging cellular

phones is becoming increasingly common and natural.

English and Technology in Africa

Despite the sociolinguistic context in which

Kiswahili dominates, the current language in education policy, which is

in operation in 2012, stipulates that English remains LOI [Language of

Instruction] for secondary school and tertiary education. This means

99.1 per cent of pupils who join secondary education coming from a

primary school where Kiswahili was the LOI have to switch to

English.

A Study in Contrasts: The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and

South Korea

There

are some 2.3 million displaced persons and refugees in the country and

323,000 DRC nationals living in refugee camps outside the country. A

humanitarian emergency persists in the more unstable parts of the DRC

and sexual violence rates remain high.

…ethnic languages are used primarily within

families, as well as within ethnic groups. The national languages serve

as ‘regional vehiculars,’ especially in urban areas….

French, in turn, is used in all ‘official’ domains, in

particular in the government and

judiciary.

English as a Worldwide Phenomenon

Nigeria, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Cameroon all

have a wide variety of indigenous languages and are seeking to develop

a degree of linguistic unity through the use of English. Rwanda’s

native language, Kinyarwanda, is spoken by 98% of the population.

Furthermore, its government is looking to achieve greater harmony with

English-speaking East African countries, while turning away from

French-speaking West African nations. These trends reflect the growing

awareness that strong English skills are a requirement to develop a

competitive economic advantage in the global

economy.

Few countries continue to

debate whether or not English should be taught. Instead, discussions of

English instruction in public schools focus on which dialect of English

is taught, how it is assessed, and how much English education is

necessary….English is often tied to development goals, expansion of

the service sector, and increased connectivity to the rest of the

world.

Conclusion

What we are witnessing is not just a massive

die-off of the world’s languages, it is the final act of the

Neolithic Revolution, with the urban agriculturalists moving on to a

different, digital plane of

existence.

Nearly one-third of the world’s population

is studying English, and it is predicted that by 2050, half of the

world’s population will be largely proficient in it. Added to

this, four of the six most populous countries in the world in 2050

(India, the United States, Nigeria and Pakistan) will have English as

an official language.

References